Microcontroller-Based

Single Knob Tuning for Satellite Operations

with Doppler Correction and Antenna Rotator Interface

I am a latecomer to the ham

radio satellites interest. In June 2023, a friend1

told me about having made contacts by way of the

Russian satellite RS-44.

I had known about the International Space Station’s FM transponder, and

had read about ‘Oscar’ satellites, but was not previously aware of a

Russian ham radio

satellite. The idea seemed exotic and

I wanted to try it myself. My friend assured me that this could be done

using a VHF/UHF capable transceiver and inexpensive Arrow antenna—actually

two antennas on one boom, with an optional built-in (low power)

duplexer.

Satellite communication

appeals to hobbyists in different ways. Hams who design, construct and

manage deployment of the

amateur satellites obviously have strong

engineering interests and abilities. For myself, I wanted to

make just one contact on that Russian satellite for the thrill of doing

so. However, it did not take long to realize that there is a lot to

learn, just to achieve the most basic level of satellite operating

proficiency.

The Arrow antenna was delivered within a few days. I mounted it at a

fixed elevation angle to a short mast, at first on a portable stand,

and later lashed with ropes to the bottom post of the back porch steps.

I disconnected the duplexer and substituted

separate coax runs to the 2 meter and 70 centimeter shared-boom

antennas. The

azimuth rotator was my wife N4EFS, who endured the blazing South

Carolina summer sun to turn the antenna by hand while I attempted to

make a first contact on RS-44.

The Arrow antenna was delivered within a few days. I mounted it at a

fixed elevation angle to a short mast, at first on a portable stand,

and later lashed with ropes to the bottom post of the back porch steps.

I disconnected the duplexer and substituted

separate coax runs to the 2 meter and 70 centimeter shared-boom

antennas. The

azimuth rotator was my wife N4EFS, who endured the blazing South

Carolina summer sun to turn the antenna by hand while I attempted to

make a first contact on RS-44.

Many ham radio satellite operators use the excellent computer program

SatPC32, which (among other features)

displays the continuously changing bearing to a selected satellite. As the

satellite crosses the sky its current azimuth can

be read by eye

from

the bottom left corner of SatPC32’s

main screen. I installed the program but did not interface it with the

rigs, or directly to the human rotator. Nevertheless, using this

limited setup we were able to

make CW QSOs with

a few patient operators.

Many ham radio satellite operators use the excellent computer program

SatPC32, which (among other features)

displays the continuously changing bearing to a selected satellite. As the

satellite crosses the sky its current azimuth can

be read by eye

from

the bottom left corner of SatPC32’s

main screen. I installed the program but did not interface it with the

rigs, or directly to the human rotator. Nevertheless, using this

limited setup we were able to

make CW QSOs with

a few patient operators.

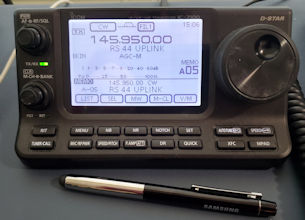

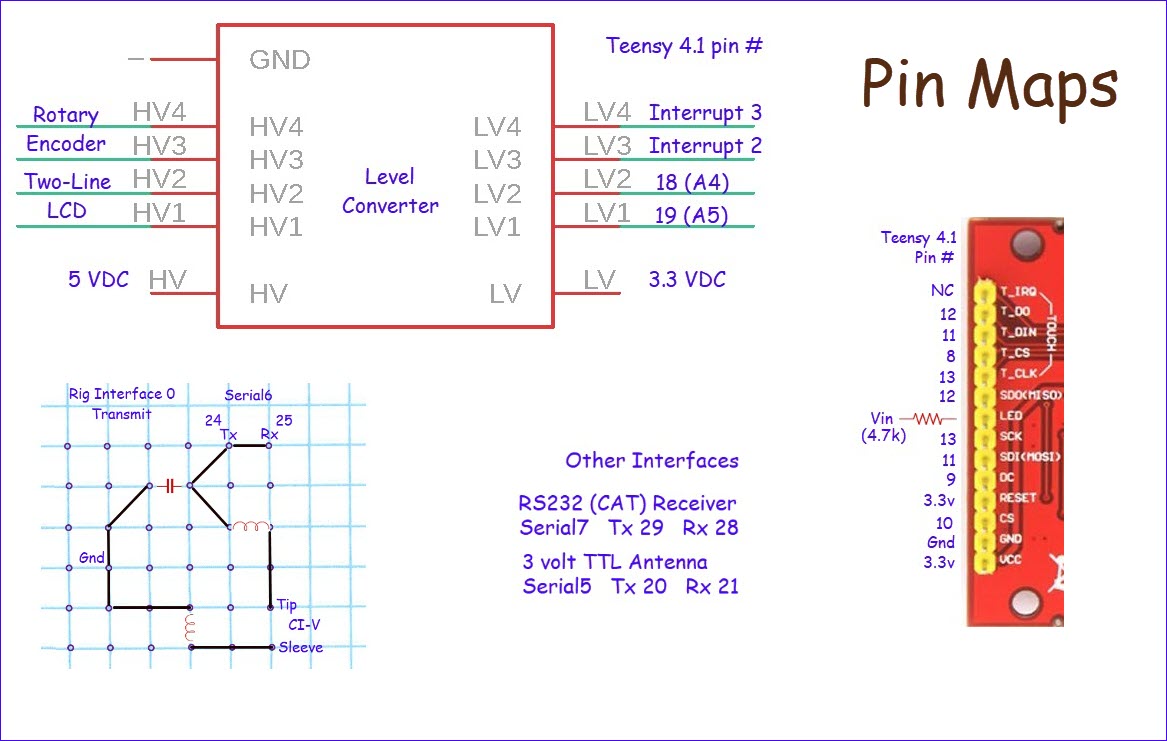

During this exploratory phase of operating I

could also hear single sideband (SSB) stations, and make their audio

intelligible for short periods by continuously

hand-tuning the

receiver VFO. There was no chance of making an SSB contact at this

stage. For successful SSB communication it would be necessary to

implement automatic Doppler frequency correction. To reiterate, the

computer was not interfaced with either the Icom

IC-7100 transmitter or

Yaesu FT-991A receiver.

RS-44 is an inverting

linear ‘bird’ (the fraternal nickname

for satellite). ‘Inverting’ means that uplink and downlink

frequency

ranges are mirror reflected. The bottom end of

the uplink band, a 60 KHz patch of the 2 meter band, maps to the top

end of the downlink band, a same-sized chunk of

the 70 centimeter ham band. Zero-beating

a received station can be challenging—It is necessary to be able to

hear one’s transmit signal from the satellite, and to be sure that it

isn’t artifact. If the received carrier tone changes pitch, reflecting

the

Doppler effect, it is a true signal. For zero-beating it is helpful to

start tuning somewhere in the ballpark of the target frequency.

Figuring out where to tune the receiver in order to hear the

transmitter led me to the idea of using a rotary encoder to tune both

transmitter and receiver synchronously. A single knob could tune the

two rigs in opposite directions, in a sense mimicking ordinary simplex

tuning. It would still be necessary to adjust the actual transmit and

receive VFOs

for the

Doppler effect.

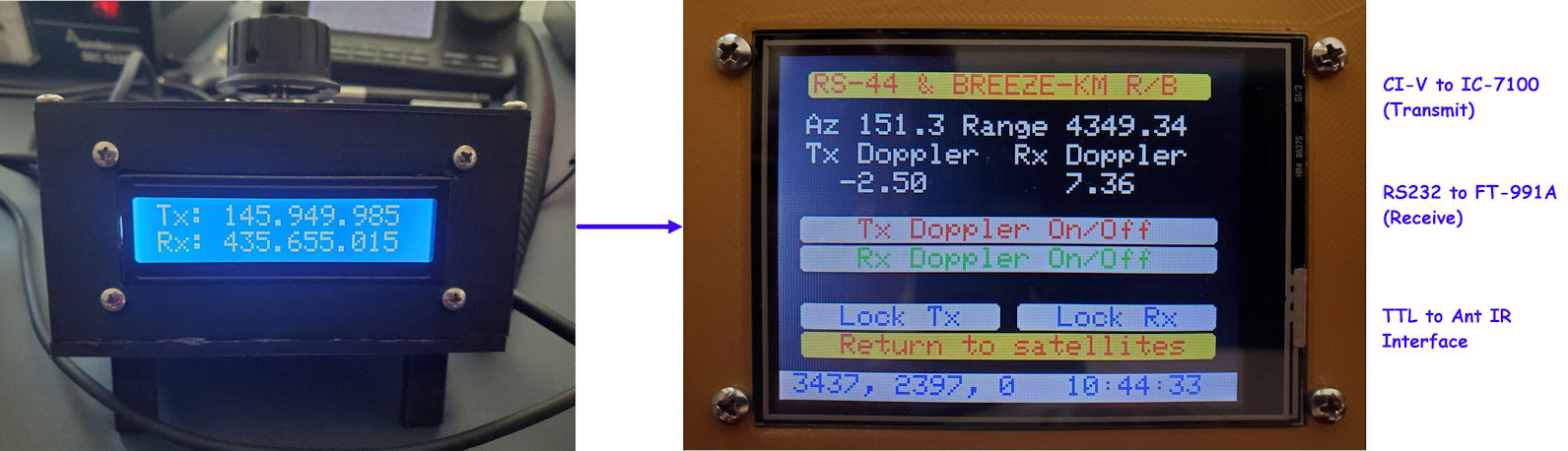

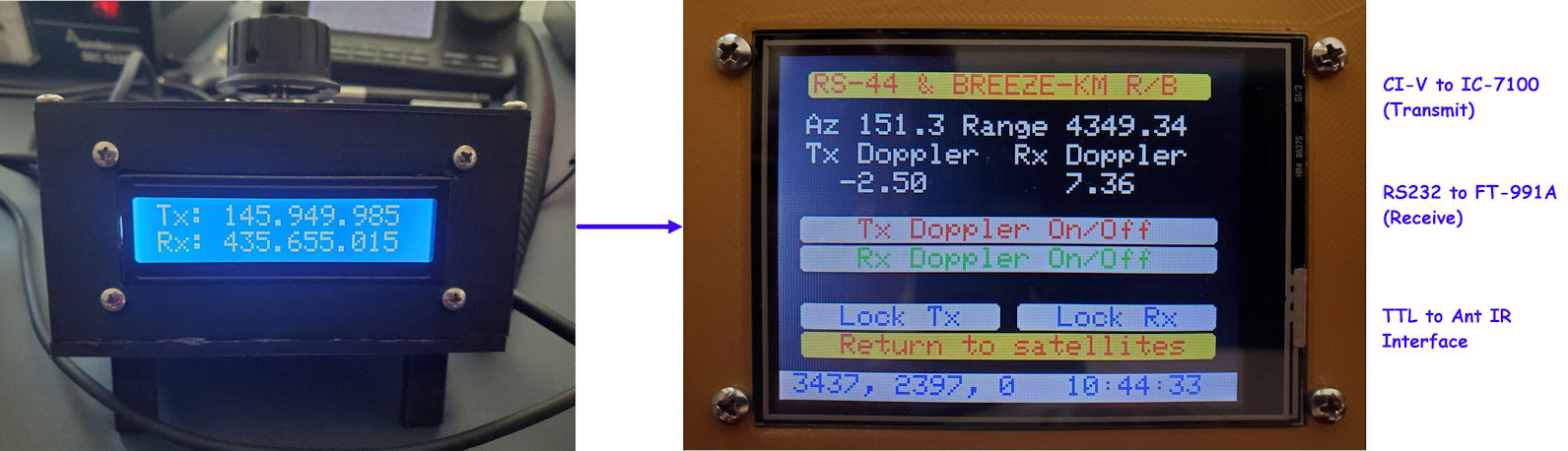

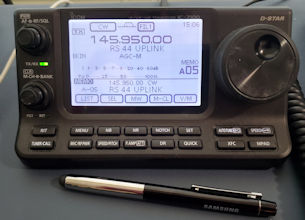

I began to think about a microcontroller-based device that could

support both one-knob linked tuning and also Doppler correction of

transmit and receive frequencies. Although only a few months have

elapsed since this concept began to form, I am no longer sure of

the order in which early parts of the plan came together. One

decision was to use a two-line LCD to display uncorrected but linked

transmit and receive frequencies (see photo at top of page). For the

microcontroller I thought of using a WiFi enabled board such as an

ESP8266, but hesitated and instead selected the Teensy 4.1, which has a

built-in microSD card slot that could be used for storing satellite and

station parameters. Teensy 4.1 also has an integral real time clock,

which would be convenient for computing time-dependent satellite

parameters. I had recently used this particular

development board

in a couple of other projects and was familiar with its basic

documented capabilities.

I began to think about a microcontroller-based device that could

support both one-knob linked tuning and also Doppler correction of

transmit and receive frequencies. Although only a few months have

elapsed since this concept began to form, I am no longer sure of

the order in which early parts of the plan came together. One

decision was to use a two-line LCD to display uncorrected but linked

transmit and receive frequencies (see photo at top of page). For the

microcontroller I thought of using a WiFi enabled board such as an

ESP8266, but hesitated and instead selected the Teensy 4.1, which has a

built-in microSD card slot that could be used for storing satellite and

station parameters. Teensy 4.1 also has an integral real time clock,

which would be convenient for computing time-dependent satellite

parameters. I had recently used this particular

development board

in a couple of other projects and was familiar with its basic

documented capabilities.

One of these previous Teensy 4.1 projects involved a

custom PCB that had extra solder pads and traces that were not required

by the

original project. Extra connection points might be handy for future

experimentation. The

future was now.

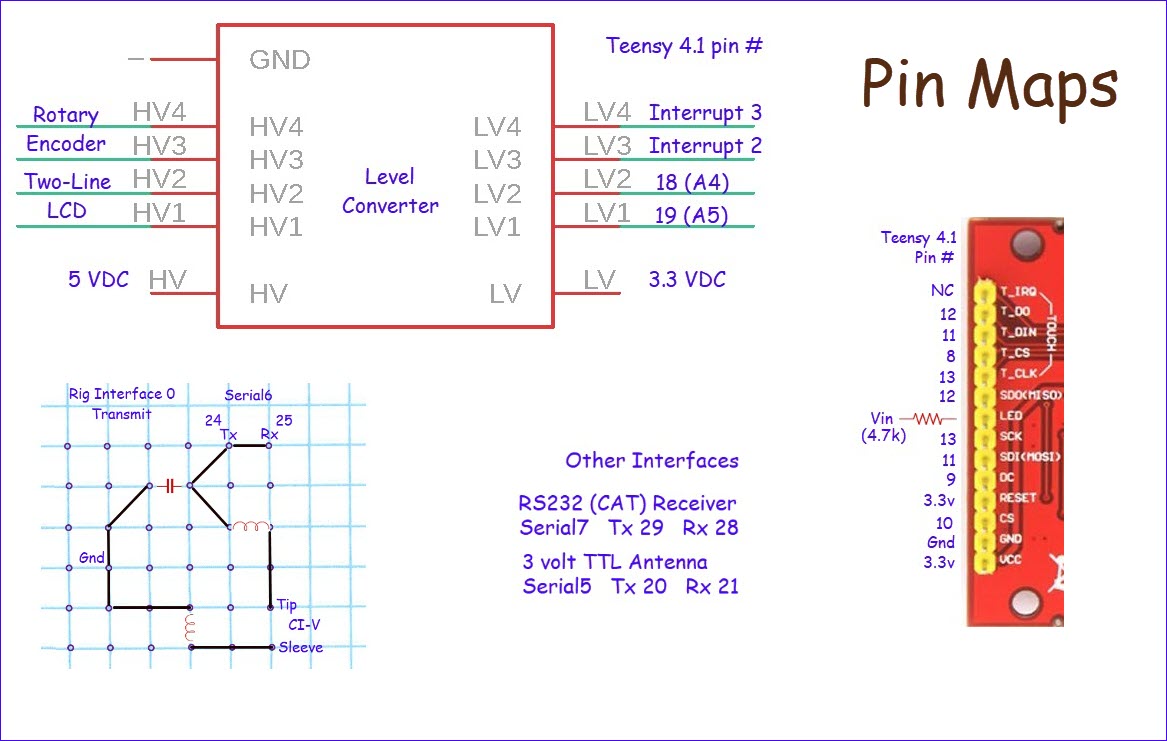

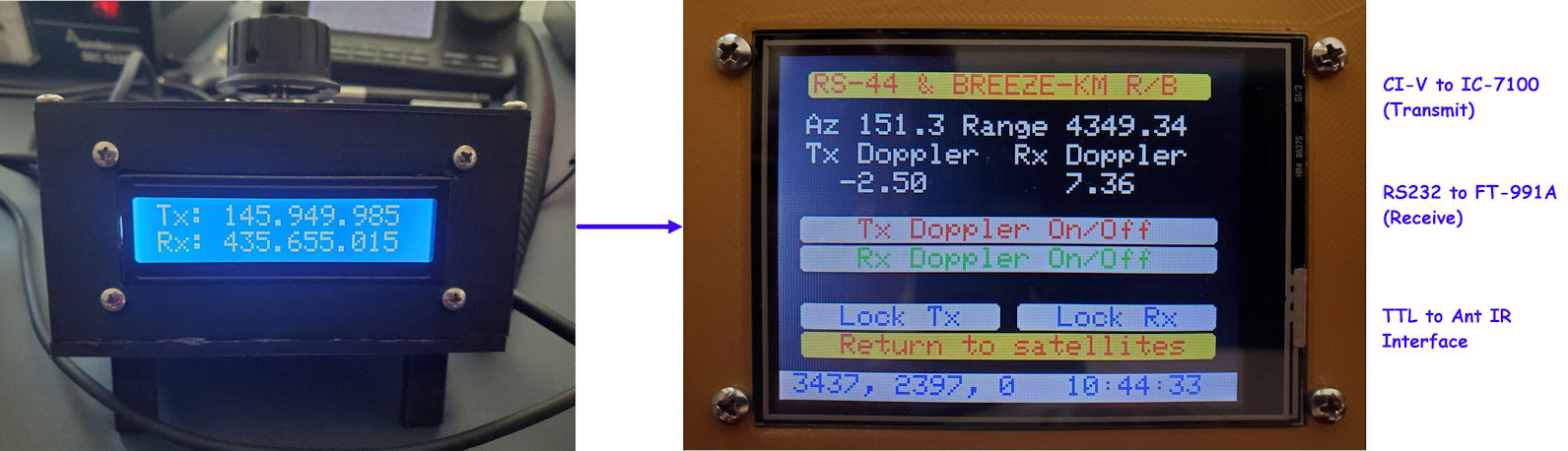

Interfacing the rotary encoder and LCD was

relatively simple, the only potential ‘gotcha’ being that rotary

encoder pulses are minimally 5 volts and Teensy 4.1 pins are not 5-volt

tolerant. Thus encoder pulses had to be converted to 3.3 volts for

connection to the microcontroller. The particular rotary encoder used

for the project (this one)

had a long cable attached, much longer than needed, so I cut it in half

and used the other half for the LCD, which had an integral 4-pin i2c

connector. I tested the

two-row LCD at 3.3 volts but

found that for satisfactory brightness and contrast it also needed 5

volts.

Under ‘Other Interfaces’

in the ‘Pin Maps’ figure (above)

there is an entry for a 3 volt TTL Antenna rotator interface. That

interface was added after the

linked tuning and

Doppler components, and is described as a separate story on this page.

Displayed frequencies are just numbers. It is possible to demonstrate

linked ‘tuning’ without tuning anything, a simulation if you will.

After completing such an exercise I began to address interfacing the

transceivers for actual VFO control. The Yaesu FT-991A, which serves as

receiver in the setup has

a DB9 jack on its back panel for either CAT or GPS. In an

earlier project the transceiver was

successfully interfaced with an ESP8266 using an RS232 to TTL adapter, so the same adapter was

selected for this project. A manufactured DB9 male

to DB9 female cable connects the Yaesu transceiver to the adapter.

Displayed frequencies are just numbers. It is possible to demonstrate

linked ‘tuning’ without tuning anything, a simulation if you will.

After completing such an exercise I began to address interfacing the

transceivers for actual VFO control. The Yaesu FT-991A, which serves as

receiver in the setup has

a DB9 jack on its back panel for either CAT or GPS. In an

earlier project the transceiver was

successfully interfaced with an ESP8266 using an RS232 to TTL adapter, so the same adapter was

selected for this project. A manufactured DB9 male

to DB9 female cable connects the Yaesu transceiver to the adapter.

The Icom IC-7100 has a 3.5 mm jack labeled ‘Remote’

on its back panel. This jack exposes the Icom 2-wire CI-V bus, data on

tip, and ground on sleeve. CI-V level is 3 volts, so nothing

special was needed for that. At some time in the past Icom had a

CI-V to RS232

interface device called CT-17 (no longer available). On examining the

CT-17 documentation I saw that in addition to an RS232-to-TTL chip, the

circuit included a capacitor and a couple of inductors (RF filtering).2 For prudence’s sake I included

these when interfacing Teensy 3.3 volt

serial to the Icom bus. The graphical representation of the CI-V

interface in the lower left

corner of the ‘Pin Maps’ illustration represents a small cut piece of

prototyping circuit board.

The

cable is a standard stereo headphone cable, with no connection to

the ring from the jack.

The software side of these rig interfaces evolved

over time, with the addition of Doppler correction

and other features. The specific Teensy serial channels used and other

details are documented in the ‘Pin Maps’ illustration,

and can also be deduced from the source code, which will be posted and

linked from near the bottom of this page. The main consideration was to

select

pins that were not needed for the Touch Screen (‘Pin

Maps’ illustration) and that preferably had

solder traces on the repurposed PCB, for easy connection.

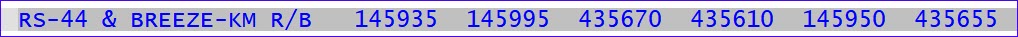

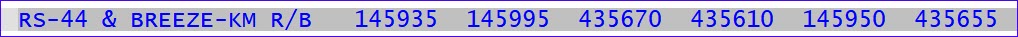

One important software detail concerns how

frequencies to be tuned for each satellite are specified. For testing,

I

hard-coded pseudo band boundaries and

twiddled the tuning knob to observe changing frequencies, but

hard-coding the band edges would not

do for practical deployment. I confess to not having used XML or any

standard way of specifying parameters. Instead, a plain text file

records transmit and receive frequencies for the satellites of

interest.

Each record starts with

the satellite name as given in the TLE file. An

example entry is shown above.

After the satellite name, each line of text consists of tab-delimited

data: transmit left boundary, <tab> transmit right boundary

<tab> receive left boundary <tab> receive right boundary,

and then optionally preferred starting frequencies, i.e. where in the

band the tuning dial should be set at the beginning of a satellite

pass.

If not otherwise specified, tuning starts in the middle of the band.

For FM satellites the left and right bounds generally specify the same

frequency. There is no need for tuning the receiver when Doppler

correction is in effect and only one frequency is used.

On to the Doppler problem... I had only a superficial understanding of

what programs like SatPC32

do internally. I knew how to compute Doppler-shifted frequency from a

source

frequency and velocity.3 I also knew that

Keplerian ‘Two-Line Elements’

or TLEs need to be refreshed fairly often in order for

programs like SatPC32 or Orbitron or similar applications to predict

satellite passes and compute their orbits

accurately. But I had no idea how these programs

do what they do, and imagined that the algorithms must be complicated.

On to the Doppler problem... I had only a superficial understanding of

what programs like SatPC32

do internally. I knew how to compute Doppler-shifted frequency from a

source

frequency and velocity.3 I also knew that

Keplerian ‘Two-Line Elements’

or TLEs need to be refreshed fairly often in order for

programs like SatPC32 or Orbitron or similar applications to predict

satellite passes and compute their orbits

accurately. But I had no idea how these programs

do what they do, and imagined that the algorithms must be complicated.

To get some sense of how to proceed I started reading about the

‘two-body’

problem, struggling to understand the relevant mathematics

and not succeeding! Then came a breakthrough. At some point in my

research the realization hit

that satellite orbit prediction programs were not solving for orbit

parameters at the application level themselves, That

problem had been

solved long ago, and encapsulated in such a way that programs had

only to invoke canned library functions. Forget orbit formulas and

their underlying math and physics—well these are good subjects to

learn, but

are not essential for writing a program or constructing a device to

tune the radio

or

rotate the antenna.

To get some sense of how to proceed I started reading about the

‘two-body’

problem, struggling to understand the relevant mathematics

and not succeeding! Then came a breakthrough. At some point in my

research the realization hit

that satellite orbit prediction programs were not solving for orbit

parameters at the application level themselves, That

problem had been

solved long ago, and encapsulated in such a way that programs had

only to invoke canned library functions. Forget orbit formulas and

their underlying math and physics—well these are good subjects to

learn, but

are not essential for writing a program or constructing a device to

tune the radio

or

rotate the antenna.

Algorithms and implementing software for

predicting positions and velocities of satellites in conjunction with

the TLEs are referred to collectively by the

label SGP4. Programs that were

originally published decades ago have

been extended and refined and ported to multiple programming languages

and computing platforms. One of these platforms (thanks to SparkFun)

is the Arduino IDE, which I use for nearly all microcontroller

programming. The SparkFun Arduino port of SGP4 comes with a couple of

easy-to-follow examples. These examples illustrate how

to initialize the model for a specific satellite by supplying the

relevant Keplerian two-line elements and our earth station location

(latitude, longitude and altitude).

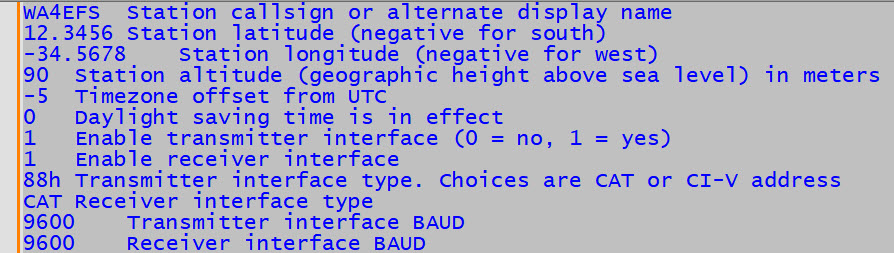

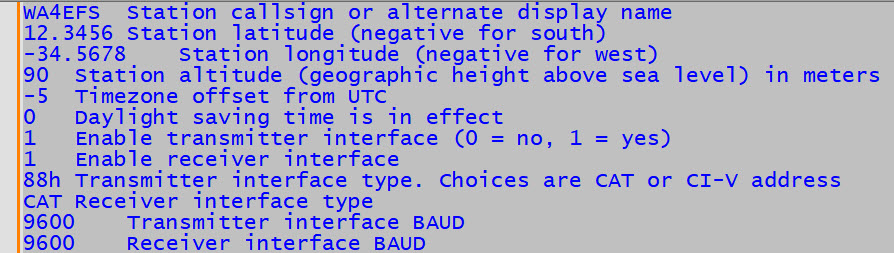

Thus, another text file! Each row of the station.txt file starts with a

parameter value, then optionally <tab> description. SGP4

requires universal time (UT) for its computations, so it is

necessary to convert Teensy time to UT. Teensy time is whatever time

zone

has been set, possibly also including the cursed Daylight Saving Time

(DST) adjustment. The real time clock’s internal format is a signed

count of the number of

seconds from January 1, 1970, a number that will overflow

in 2037. Therefore, it is pointless to worry about DST after year 2037.

By the way, the SGP4

Arduino library code understands British Summer Time, which ends on a

different

day than United States DST. Argh!

Thus, another text file! Each row of the station.txt file starts with a

parameter value, then optionally <tab> description. SGP4

requires universal time (UT) for its computations, so it is

necessary to convert Teensy time to UT. Teensy time is whatever time

zone

has been set, possibly also including the cursed Daylight Saving Time

(DST) adjustment. The real time clock’s internal format is a signed

count of the number of

seconds from January 1, 1970, a number that will overflow

in 2037. Therefore, it is pointless to worry about DST after year 2037.

By the way, the SGP4

Arduino library code understands British Summer Time, which ends on a

different

day than United States DST. Argh!

It would be possible to initialize the Teensy

real-time

clock to

UT and ignore DST, but many users (myself included) are more

comfortable scheduling their radio operating time by wrist watch or

wall clock.

Another option would be to move to Hawaii, where it is summer nearly

all

the time and there is no need for DST. The way in which the

microcontroller code handles DST is currently in flux. I made a table

of start and end times for the present through year 2037, but have not

fully implemented this approach.

This project story is not intended to be a ‘How to’, although

sufficient

detail

is included to support reproducing essential features of the project.

Pin numbers

for interfacing both internal and external components are identified

redundantly in the ‘Pin Maps’ illustration and sketch. Additionally,

the required

parameter files TLEs (e.g. amateur.txt), frequencies.txt and

station.txt have been described. Updating TLEs requires an extra step

as TLEs cannot be directly downloaded to the device (at present).

Instead the TLEs file must be copied to a microSD card.

This project story is not intended to be a ‘How to’, although

sufficient

detail

is included to support reproducing essential features of the project.

Pin numbers

for interfacing both internal and external components are identified

redundantly in the ‘Pin Maps’ illustration and sketch. Additionally,

the required

parameter files TLEs (e.g. amateur.txt), frequencies.txt and

station.txt have been described. Updating TLEs requires an extra step

as TLEs cannot be directly downloaded to the device (at present).

Instead the TLEs file must be copied to a microSD card.

Removing and

inserting the microSD card requires minor surgery. My particular

3D-printed project

‘enclosure’ is open on the front and right-hand side, so forceps can be

used to access the card slot. It is neither

necessary nor

desirable to clamp or lock the forceps—a minimal grip suffices!

However,

the unit should be powered-down when

removing or inserting a card. The illuminated LED in the staged

photo (right) is misleading. Powering down the device may be considered

analogous to

administering anesthesia.

By convention, lower sideband is used below 20

meters, while upper sideband is used on 20 meters and above. However,

because inverting linear satellite uplink and downlink bands are mirror

images, all signals received

by the satellite

are inverted when retransmitted, in effect causing the

downlink sideband to be opposite to the uplink sideband. Thus

lower-sideband should be used for uplink, whether VHF or UHF, in order

to be received as upper sideband on the downlink band. Ham radio

transceivers typically default to the aforementioned convention.

Therefore

it may be necessary to change the transmit mode explicitly to lower

sideband for

satellite transmission.

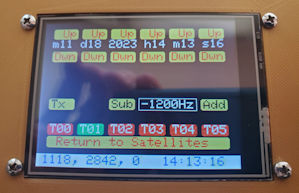

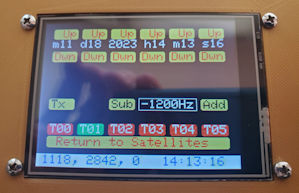

With mirror-image tuning of uncorrected transmit and receive

frequencies, along with Doppler correction of both VFOs, my single

sideband transmit frequency was approximately –1200 Hz from the

frequency that I was trying to zero-beat, for example an SSB station

calling CQ. This value was ascertained experimentally. I first tuned

the receiver to an inactive test frequency, then

unplugged the transmit interface and tuned the transmitter (using the

rig’s main tuning dial) from its Doppler

corrected frequency to the zero-beat frequency as quickly as

possible, making note of the delta.

This ‘experiment’ was repeated at a small number of different test

frequencies until I felt confident of the

delta value (to an acceptable approximation). It is challenging to make

such observations when Doppler

is changing rapidly. I have heard other stations transmit long streams

of Morse dots, probably for the same purpose.

With mirror-image tuning of uncorrected transmit and receive

frequencies, along with Doppler correction of both VFOs, my single

sideband transmit frequency was approximately –1200 Hz from the

frequency that I was trying to zero-beat, for example an SSB station

calling CQ. This value was ascertained experimentally. I first tuned

the receiver to an inactive test frequency, then

unplugged the transmit interface and tuned the transmitter (using the

rig’s main tuning dial) from its Doppler

corrected frequency to the zero-beat frequency as quickly as

possible, making note of the delta.

This ‘experiment’ was repeated at a small number of different test

frequencies until I felt confident of the

delta value (to an acceptable approximation). It is challenging to make

such observations when Doppler

is changing rapidly. I have heard other stations transmit long streams

of Morse dots, probably for the same purpose.

The frequency discrepancy may have a

simple

explanation—I don’t know.

In any

case, the problem was addressed empirically by making provision for a

signed correction to be applied to either transmit or receive VFO, or

apportioned to both. I had no evidence as to which VFO should be

adjusted, but entered

the correction

for the transmit frequency. That can be changed, of course. When a

value for the correction is entered or changed (‘Tools’

screen photo above left) the adjusted value is automatically stored in

EEPROM and

restored

when the device is restarted. The correction does not apply to

single-frequency transponders (e.g., FM satellites). If a correction is

needed there, it can be made in the frequency file. However, it is not

generally necessary to adjust the transmit frequency when working an FM

satellite.

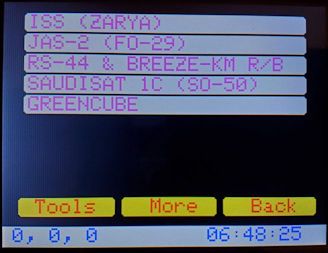

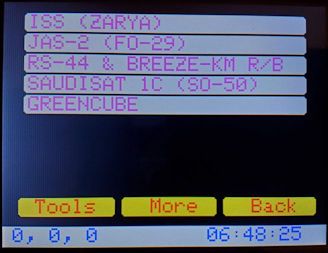

The satellite selection screen (main screen) has room for eight or

nine

satellite names. Buttons labeled ‘More’ and ‘Back’ in the photo were

planned for

paging through a longer list of names. However, the paging function has

not (yet) been implemented, chiefly because there are not a great many

active ham radio satellites, or hours in the day to pursue them. Note,

for example, the small number of chiefly blue rows on the AMSAT

Status Page.

The satellite selection screen (main screen) has room for eight or

nine

satellite names. Buttons labeled ‘More’ and ‘Back’ in the photo were

planned for

paging through a longer list of names. However, the paging function has

not (yet) been implemented, chiefly because there are not a great many

active ham radio satellites, or hours in the day to pursue them. Note,

for example, the small number of chiefly blue rows on the AMSAT

Status Page.

My home bench projects are never completely

finished.

They reach stable points, where they are either used or set aside while

ideas percolate. The current microcontroller code version 1.1

may be considered a source of ideas for similar projects. The rig

interfaces are specific to my personal use (Icom transmitter and Yaesu

receiver) but could be adapted or generalized to work with other ham

radio transceivers. The posted sketch was developed with Arduino IDE

2.2.1. Of course, #include libraries listed near the top of the sketch

are required for successful compilation.

Addendum 1:

In truth, the surgical method of removing and inserting a microSD card

for TLE updates was not ideal. Much better would be to expose the

card slot externally, as it would normally be on a consumer device.

Doing this turned out to be a snap, using a microSD to microSD

extension cable, 15 cm in length (longer than needed). I had no idea

such a thing exists, but found one here (photo left). However, this improvement was

soon superseded by another.

Addendum 1:

In truth, the surgical method of removing and inserting a microSD card

for TLE updates was not ideal. Much better would be to expose the

card slot externally, as it would normally be on a consumer device.

Doing this turned out to be a snap, using a microSD to microSD

extension cable, 15 cm in length (longer than needed). I had no idea

such a thing exists, but found one here (photo left). However, this improvement was

soon superseded by another.

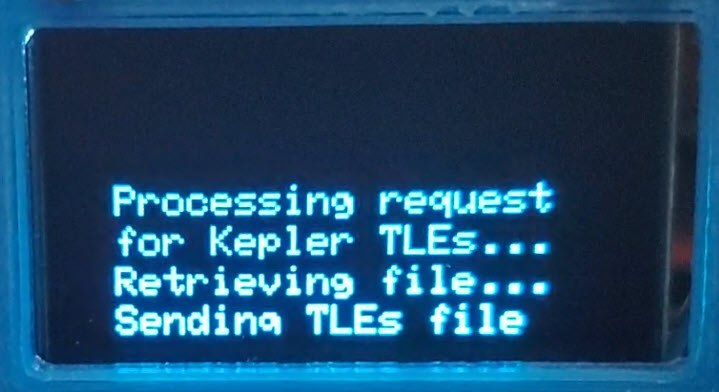

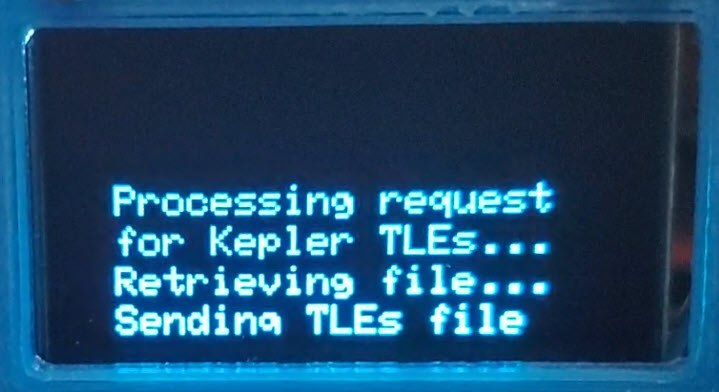

The Teensy 4.1 does not have built-in WiFi

capability, however, several ESP8266 WiFi-enabled boards were on-hand

and available to use. Why not just add another microcontroller to the

project? —There was room in the enclosure, though just barely! It

seemed wasteful, in a way, to dedicate an ESP8266 to the sole purpose

of updating TLEs, so I thought of something else to do with it. In

addition to making the WiFi connection needed for downloading TLEs

directly from the Internet, the ESP8266 could also be used to display

satellite passes diagrammatically, as some computer tracking

applications do. This whole story will have to be told on a future

project page. For the present I remark that the microSD extension was

nice to have for about one week after installation, whereupon it was no

longer needed!

Demo video: Sat Helper

Endnotes

1. AL7JX Glen Fuller

2. Inductor values

specified in the CT-17 schematic diagram

are 1 μH and the capacitor is 100

pF.

3. If the satellite’s

distance from the station (range) is obtained once per second then the

distance traveled in one second is equal to the difference between two

successive range computations. Velocity is directed (signed) distance

divided by

time.

Let v

stand for the satellite’s velocity with respect to the station, and C stand for the speed of light in

meters per second. The Doppler corrected frequency is the uncorrected

frequency multiplied by C/(C+v).

Project descriptions

on this page are intended for entertainment only.

The author makes no claim as to the accuracy or completeness of the

information presented. In no event will the author be liable for any

damages, lost effort, inability to carry out a similar project, or to

reproduce a claimed result, or anything else relating to a decision

to use the information on this page.

The Arrow antenna was delivered within a few days. I mounted it at a

fixed elevation angle to a short mast, at first on a portable stand,

and later lashed with ropes to the bottom post of the back porch steps.

I disconnected the duplexer and substituted

separate coax runs to the 2 meter and 70 centimeter shared-boom

antennas. The

azimuth rotator was my wife N4EFS, who endured the blazing South

Carolina summer sun to turn the antenna by hand while I attempted to

make a first contact on RS-44.

The Arrow antenna was delivered within a few days. I mounted it at a

fixed elevation angle to a short mast, at first on a portable stand,

and later lashed with ropes to the bottom post of the back porch steps.

I disconnected the duplexer and substituted

separate coax runs to the 2 meter and 70 centimeter shared-boom

antennas. The

azimuth rotator was my wife N4EFS, who endured the blazing South

Carolina summer sun to turn the antenna by hand while I attempted to

make a first contact on RS-44. Many ham radio satellite operators use the excellent computer program

SatPC32, which (among other features)

displays the continuously changing bearing to a selected satellite. As the

satellite crosses the sky its current azimuth can

be read by eye

from

the bottom left corner of SatPC32’s

main screen. I installed the program but did not interface it with the

rigs, or directly to the human rotator. Nevertheless, using this

limited setup we were able to

make CW QSOs with

a few patient operators.

Many ham radio satellite operators use the excellent computer program

SatPC32, which (among other features)

displays the continuously changing bearing to a selected satellite. As the

satellite crosses the sky its current azimuth can

be read by eye

from

the bottom left corner of SatPC32’s

main screen. I installed the program but did not interface it with the

rigs, or directly to the human rotator. Nevertheless, using this

limited setup we were able to

make CW QSOs with

a few patient operators. I began to think about a microcontroller-based device that could

support both one-knob linked tuning and also Doppler correction of

transmit and receive frequencies. Although only a few months have

elapsed since this concept began to form, I am no longer sure of

the order in which early parts of the plan came together. One

decision was to use a two-line LCD to display uncorrected but linked

transmit and receive frequencies (see photo at top of page). For the

microcontroller I thought of using a WiFi enabled board such as an

ESP8266, but hesitated and instead selected the Teensy 4.1, which has a

built-in microSD card slot that could be used for storing satellite and

station parameters. Teensy 4.1 also has an integral real time clock,

which would be convenient for computing time-dependent satellite

parameters. I had recently used this particular

development board

in a couple of other projects and was familiar with its basic

documented capabilities.

I began to think about a microcontroller-based device that could

support both one-knob linked tuning and also Doppler correction of

transmit and receive frequencies. Although only a few months have

elapsed since this concept began to form, I am no longer sure of

the order in which early parts of the plan came together. One

decision was to use a two-line LCD to display uncorrected but linked

transmit and receive frequencies (see photo at top of page). For the

microcontroller I thought of using a WiFi enabled board such as an

ESP8266, but hesitated and instead selected the Teensy 4.1, which has a

built-in microSD card slot that could be used for storing satellite and

station parameters. Teensy 4.1 also has an integral real time clock,

which would be convenient for computing time-dependent satellite

parameters. I had recently used this particular

development board

in a couple of other projects and was familiar with its basic

documented capabilities.

Displayed frequencies are just numbers. It is possible to demonstrate

linked ‘tuning’ without tuning anything, a simulation if you will.

After completing such an exercise I began to address interfacing the

transceivers for actual VFO control. The Yaesu FT-991A, which serves as

receiver in the setup has

a DB9 jack on its back panel for either CAT or GPS. In an

earlier project the transceiver was

successfully interfaced with an ESP8266 using an RS232 to TTL adapter, so the same adapter was

selected for this project. A manufactured DB9 male

to DB9 female cable connects the Yaesu transceiver to the adapter.

Displayed frequencies are just numbers. It is possible to demonstrate

linked ‘tuning’ without tuning anything, a simulation if you will.

After completing such an exercise I began to address interfacing the

transceivers for actual VFO control. The Yaesu FT-991A, which serves as

receiver in the setup has

a DB9 jack on its back panel for either CAT or GPS. In an

earlier project the transceiver was

successfully interfaced with an ESP8266 using an RS232 to TTL adapter, so the same adapter was

selected for this project. A manufactured DB9 male

to DB9 female cable connects the Yaesu transceiver to the adapter.

To get some sense of how to proceed I started reading about the

‘two-body’

problem, struggling to understand the relevant mathematics

and not succeeding! Then came a breakthrough. At some point in my

research the realization hit

that satellite orbit prediction programs were not solving for orbit

parameters at the application level themselves, That

problem had been

solved long ago, and encapsulated in such a way that programs had

only to invoke canned library functions. Forget orbit formulas and

their underlying math and physics—well these are good subjects to

learn, but

are not essential for writing a program or constructing a device to

tune the radio

or

rotate the antenna.

To get some sense of how to proceed I started reading about the

‘two-body’

problem, struggling to understand the relevant mathematics

and not succeeding! Then came a breakthrough. At some point in my

research the realization hit

that satellite orbit prediction programs were not solving for orbit

parameters at the application level themselves, That

problem had been

solved long ago, and encapsulated in such a way that programs had

only to invoke canned library functions. Forget orbit formulas and

their underlying math and physics—well these are good subjects to

learn, but

are not essential for writing a program or constructing a device to

tune the radio

or

rotate the antenna.

Thus, another text file! Each row of the station.txt file starts with a

parameter value, then optionally <tab> description. SGP4

requires universal time (UT) for its computations, so it is

necessary to convert Teensy time to UT. Teensy time is whatever time

zone

has been set, possibly also including the cursed Daylight Saving Time

(DST) adjustment. The real time clock’s internal format is a signed

count of the number of

seconds from January 1, 1970, a number that will overflow

in 2037. Therefore, it is pointless to worry about DST after year 2037.

By the way, the SGP4

Arduino library code understands British Summer Time, which ends on a

different

day than United States DST. Argh!

Thus, another text file! Each row of the station.txt file starts with a

parameter value, then optionally <tab> description. SGP4

requires universal time (UT) for its computations, so it is

necessary to convert Teensy time to UT. Teensy time is whatever time

zone

has been set, possibly also including the cursed Daylight Saving Time

(DST) adjustment. The real time clock’s internal format is a signed

count of the number of

seconds from January 1, 1970, a number that will overflow

in 2037. Therefore, it is pointless to worry about DST after year 2037.

By the way, the SGP4

Arduino library code understands British Summer Time, which ends on a

different

day than United States DST. Argh! This project story is not intended to be a ‘How to’, although

sufficient

detail

is included to support reproducing essential features of the project.

Pin numbers

for interfacing both internal and external components are identified

redundantly in the ‘Pin Maps’ illustration and sketch. Additionally,

the required

parameter files TLEs (e.g. amateur.txt), frequencies.txt and

station.txt have been described. Updating TLEs requires an extra step

as TLEs cannot be directly downloaded to the device (at present).

Instead the TLEs file must be copied to a microSD card.

This project story is not intended to be a ‘How to’, although

sufficient

detail

is included to support reproducing essential features of the project.

Pin numbers

for interfacing both internal and external components are identified

redundantly in the ‘Pin Maps’ illustration and sketch. Additionally,

the required

parameter files TLEs (e.g. amateur.txt), frequencies.txt and

station.txt have been described. Updating TLEs requires an extra step

as TLEs cannot be directly downloaded to the device (at present).

Instead the TLEs file must be copied to a microSD card. With mirror-image tuning of uncorrected transmit and receive

frequencies, along with Doppler correction of both VFOs, my single

sideband transmit frequency was approximately –1200 Hz from the

frequency that I was trying to zero-beat, for example an SSB station

calling CQ. This value was ascertained experimentally. I first tuned

the receiver to an inactive test frequency, then

unplugged the transmit interface and tuned the transmitter (using the

rig’s main tuning dial) from its Doppler

corrected frequency to the zero-beat frequency as quickly as

possible, making note of the delta.

This ‘experiment’ was repeated at a small number of different test

frequencies until I felt confident of the

delta value (to an acceptable approximation). It is challenging to make

such observations when Doppler

is changing rapidly. I have heard other stations transmit long streams

of Morse dots, probably for the same purpose.

With mirror-image tuning of uncorrected transmit and receive

frequencies, along with Doppler correction of both VFOs, my single

sideband transmit frequency was approximately –1200 Hz from the

frequency that I was trying to zero-beat, for example an SSB station

calling CQ. This value was ascertained experimentally. I first tuned

the receiver to an inactive test frequency, then

unplugged the transmit interface and tuned the transmitter (using the

rig’s main tuning dial) from its Doppler

corrected frequency to the zero-beat frequency as quickly as

possible, making note of the delta.

This ‘experiment’ was repeated at a small number of different test

frequencies until I felt confident of the

delta value (to an acceptable approximation). It is challenging to make

such observations when Doppler

is changing rapidly. I have heard other stations transmit long streams

of Morse dots, probably for the same purpose. The satellite selection screen (main screen) has room for eight or

nine

satellite names. Buttons labeled ‘More’ and ‘Back’ in the photo were

planned for

paging through a longer list of names. However, the paging function has

not (yet) been implemented, chiefly because there are not a great many

active ham radio satellites, or hours in the day to pursue them. Note,

for example, the small number of chiefly blue rows on the AMSAT

Status Page.

The satellite selection screen (main screen) has room for eight or

nine

satellite names. Buttons labeled ‘More’ and ‘Back’ in the photo were

planned for

paging through a longer list of names. However, the paging function has

not (yet) been implemented, chiefly because there are not a great many

active ham radio satellites, or hours in the day to pursue them. Note,

for example, the small number of chiefly blue rows on the AMSAT

Status Page.

Addendum 1:

In truth, the surgical method of removing and inserting a microSD card

for TLE updates was not ideal. Much better would be to expose the

card slot externally, as it would normally be on a consumer device.

Doing this turned out to be a snap, using a microSD to microSD

extension cable, 15 cm in length (longer than needed). I had no idea

such a thing exists, but found one here (photo left). However, this improvement was

soon superseded by another.

Addendum 1:

In truth, the surgical method of removing and inserting a microSD card

for TLE updates was not ideal. Much better would be to expose the

card slot externally, as it would normally be on a consumer device.

Doing this turned out to be a snap, using a microSD to microSD

extension cable, 15 cm in length (longer than needed). I had no idea

such a thing exists, but found one here (photo left). However, this improvement was

soon superseded by another.