Today is Valentine’s Day. In place of sending her flowers I wrote my

sweetheart a love letter. I could have handed her the letter, but

instead Emailed it. Of course, it would not be appropriate to

reveal the contents of the letter here--or anywhere. However, I confess

that it included a little made-up rhyme. Sweethearts tend to be

forgiving of such things. It is, as they say, “the thought that

counts.” Well, here is the rhyme.

I neglected to mention that in the tradition of lovers through the ages, my sweetheart and I share a secret code. We do not really need one, and if we did Pretty Good Privacy[1] would surely suffice. But then... Lovers do not use someone else’s secret code to whisper their secrets!

The need to write in ways that conceal rather than reveal information may be as old as writing--I do not know. How many children have taught themselves mirror writing, while imagining they have discovered a way of recording secrets?

In any case, this page is not about the history of codes. Nor is it about mathematical research or about quantum computing. Several very good books have been written about codes and codebreaking. Among those I have read, my favorite is Simon Singh’s The Code Book (Doubleday, 1999).

In this page I intend only to describe one or two amateur programming ideas or experiments, primarily from an entertainment point of view. I have always felt that doing something--experimenting or solving a puzzle--contributes to more durable understanding than just reading about the thing.

My Valentine’s Day letter used a simple and secure code, a one-time pad.[2] This is similar to the encryption method used by the German side in World War II, which as we know was eventually “broken” by heroic means. However, the successes of Bletchley Park depended in part on knowledge of the Enigma machine, the device that created the cipher. Without this knowledge it would not have been possible to decipher intercepted messages. Operator carelessness was also a factor.[3] As long as encryption keys are not compromised, messages encoded in this way are unbreakable.

To generate a pad programmatically one uses a pseudo-random number generator, i.e., the random function of a programming language. This is perhaps the first point of potential failure. Some older random number generators were unsound, and in the worst case generated large cycles of repeating numbers. However, due to improved algorithms and larger word size modern programming languages boast better--more trustworthy--pseudo-random number generators.

Another advance in the computing art is of course the ease of storing an immense pad. Micro SD cards of multi-gigabyte capacity can easily be purchased at the corner store. One can construct an encryption key and, using one of these amazing microcards, hide it in a crack in the wall. (I have not done that, so please don’t look for cracks in my wall.)

The Valentine’s Day pad consists of 1000 text files, each containing 1000 lines of 100 characters per line. It is a mere 100 megabytes in size, the tiniest fraction of a micro SD card. In theory, at any character position of any line in any of the one thousand files, each of the printable ASCII characters is equally likely.

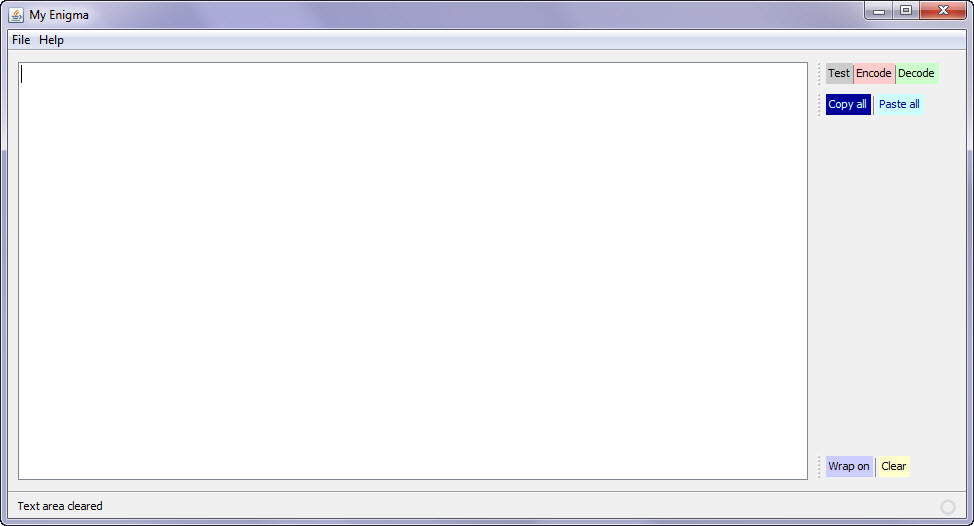

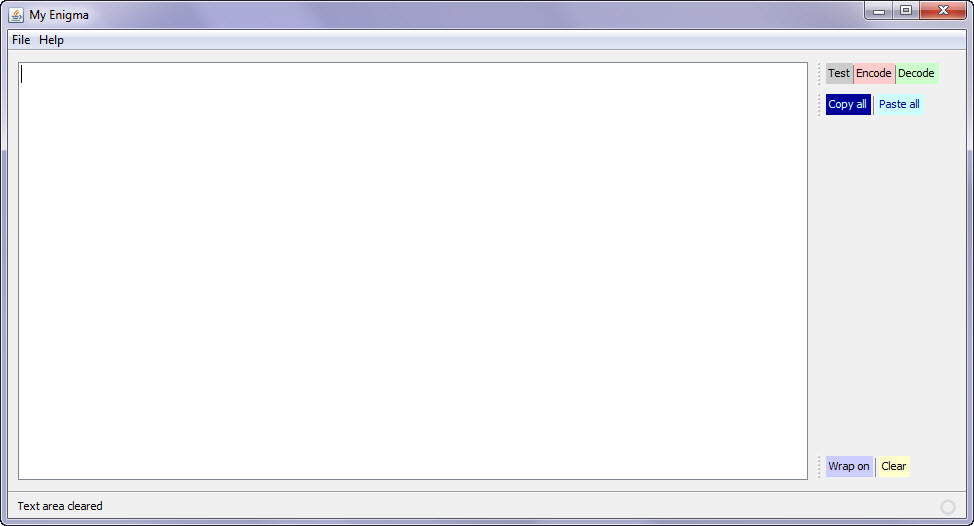

Applications need a user interface--well, most do. Certainly if one has to deal with volumes of gibberish, a friendly interface is desirable. The one that I made for Valentine’s Day was put together in the Netbeans IDE. To encipher a message one can type directly into the program’s text box or paste from the clipboard. The Encode button encrypts the text, using a pad that starts at a random character of a random line of a random file. Similarly the Decode button decrypts it. It is possible to encrypt the encrypted text, and so on, but there wouldn’t be much point in that.

Like thousands of others I first came to learn about a new kind of cipher that did not require sending a key, by reading Martin Gardner’s Mathematical Games column in Scientific American, August 1977. [4] The “public key” encryption concept was based on the asymmetry of multiplication and factoring. Multiplication is easy, factoring hard. That much I understood, but the details were shaky. Maybe I did not try hard enough, or possibly I was frightened by big numbers. My initial understanding of RSA was roughly equivalent to my current understanding of Shor’s algorithm.[5] (And the latter is definitely due to laziness.)

Modular

arithmetic makes big numbers

smaller. For example, to use Fermat’s theorem a p

- 1 ≡ 1(modulo p) it isn’t

necessary to compute a

to the p −

1th power. If it were, the enterprise

would fail.

Modular

arithmetic makes big numbers

smaller. For example, to use Fermat’s theorem a p

- 1 ≡ 1(modulo p) it isn’t

necessary to compute a

to the p −

1th power. If it were, the enterprise

would fail.

MUMPS is not a mathematical language. However, the verbosely commented function definition (left) shows how very few multiplications are needed to compute a modular result, even when the numbers involved are very large.

At some point I decided to try out RSA using manageable primes and a very short message. This can be done using a calculator, without programming. However, I used Delphi (Object Pascal) for this study. Delphi and its successors are fine products, but... I have encountered frustration when porting something from an older version to a more recent one. The “encryption studies” Delphi project included some components that are not supported in Embarcadero XE2 and later versions. In practical terms that means I have to drag the old computer from the closet--or lift it, which is worse--and fire up Delphi in order to verify my memory about this part of my story.

The old computer has something wrong on the motherboard--not the battery, which I replaced. It needs to be “charged up” for a while before it will boot. That is why I am including this irrelevant information. It is charging as I write.

OK, got it! Had to copy a .dll from the old computer to the folder where the “encryption studies” executable is stored on my current working computer. This problem could probably have been avoided by compiling the .dll into the executable to begin with.

Interesting!

I had forgotten about the DES part... Upon clicking the

“Generate” button (lower left), the program finds two 4-digit primes

and computes their product.

Strictly speaking, the key should be longer than the test message. However, the idea should be clear enough, if the demonstration is a little sloppy.

The demonstration (bottom right of form) consists of numbered steps. Each step has an associated button except step 3, in which the test message is entered.

For the illustration on the left, I clicked the step 1 and step 2 buttons in turn, to compute R and phi(R), and then to generate suitable values n and m whose product is congruent to 1 (mod phi(R)).

A default test message is shown in step 3. Note that to compute phi(R) (the number of numbers between 1 and R − 1 that are relatively prime to R) requires knowledge of the factors of R. phi(R) = (P − 1) ∙ (Q − 1).

Step 4 encodes the message using the public key R and n. While the message is decoded using the private key R and m in the final step.

Many superior explanations of public key encryption may be found on the Internet, some including simple computational examples. One approach to enhancing understanding, as illustrated here, is to program the computations that make up the steps of the algorithm, bearing in mind that real-world applications of public key encryption require much larger numbers (such that R is not factorable by ordinary means) and hence more sophisticated computational methods.

One final remark... If I ever travel on the Trans-Siberian Railway from Moscow to Vladivostok, I will leave all this stuff at home--won’t need it anyway, because my sweetheart will be with me.

[1] http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pretty_Good_Privacy

[2] http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/One-time_pad

[3] Machine settings were sometimes guessable and sometimes reused.

[4] Reprinted in: Martin Gardner, Penrose Tiles to Trapdoor Ciphers (W. H. Freeman, 1989).

[5] http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Shor’s_algorithm

I neglected to mention that in the tradition of lovers through the ages, my sweetheart and I share a secret code. We do not really need one, and if we did Pretty Good Privacy[1] would surely suffice. But then... Lovers do not use someone else’s secret code to whisper their secrets!

The need to write in ways that conceal rather than reveal information may be as old as writing--I do not know. How many children have taught themselves mirror writing, while imagining they have discovered a way of recording secrets?

In any case, this page is not about the history of codes. Nor is it about mathematical research or about quantum computing. Several very good books have been written about codes and codebreaking. Among those I have read, my favorite is Simon Singh’s The Code Book (Doubleday, 1999).

In this page I intend only to describe one or two amateur programming ideas or experiments, primarily from an entertainment point of view. I have always felt that doing something--experimenting or solving a puzzle--contributes to more durable understanding than just reading about the thing.

My Valentine’s Day letter used a simple and secure code, a one-time pad.[2] This is similar to the encryption method used by the German side in World War II, which as we know was eventually “broken” by heroic means. However, the successes of Bletchley Park depended in part on knowledge of the Enigma machine, the device that created the cipher. Without this knowledge it would not have been possible to decipher intercepted messages. Operator carelessness was also a factor.[3] As long as encryption keys are not compromised, messages encoded in this way are unbreakable.

To generate a pad programmatically one uses a pseudo-random number generator, i.e., the random function of a programming language. This is perhaps the first point of potential failure. Some older random number generators were unsound, and in the worst case generated large cycles of repeating numbers. However, due to improved algorithms and larger word size modern programming languages boast better--more trustworthy--pseudo-random number generators.

Another advance in the computing art is of course the ease of storing an immense pad. Micro SD cards of multi-gigabyte capacity can easily be purchased at the corner store. One can construct an encryption key and, using one of these amazing microcards, hide it in a crack in the wall. (I have not done that, so please don’t look for cracks in my wall.)

The Valentine’s Day pad consists of 1000 text files, each containing 1000 lines of 100 characters per line. It is a mere 100 megabytes in size, the tiniest fraction of a micro SD card. In theory, at any character position of any line in any of the one thousand files, each of the printable ASCII characters is equally likely.

Applications need a user interface--well, most do. Certainly if one has to deal with volumes of gibberish, a friendly interface is desirable. The one that I made for Valentine’s Day was put together in the Netbeans IDE. To encipher a message one can type directly into the program’s text box or paste from the clipboard. The Encode button encrypts the text, using a pad that starts at a random character of a random line of a random file. Similarly the Decode button decrypts it. It is possible to encrypt the encrypted text, and so on, but there wouldn’t be much point in that.

Public

Key Cryptography

Like thousands of others I first came to learn about a new kind of cipher that did not require sending a key, by reading Martin Gardner’s Mathematical Games column in Scientific American, August 1977. [4] The “public key” encryption concept was based on the asymmetry of multiplication and factoring. Multiplication is easy, factoring hard. That much I understood, but the details were shaky. Maybe I did not try hard enough, or possibly I was frightened by big numbers. My initial understanding of RSA was roughly equivalent to my current understanding of Shor’s algorithm.[5] (And the latter is definitely due to laziness.)

Modular

arithmetic makes big numbers

smaller. For example, to use Fermat’s theorem a p

- 1 ≡ 1(modulo p) it isn’t

necessary to compute a

to the p −

1th power. If it were, the enterprise

would fail.

Modular

arithmetic makes big numbers

smaller. For example, to use Fermat’s theorem a p

- 1 ≡ 1(modulo p) it isn’t

necessary to compute a

to the p −

1th power. If it were, the enterprise

would fail.MUMPS is not a mathematical language. However, the verbosely commented function definition (left) shows how very few multiplications are needed to compute a modular result, even when the numbers involved are very large.

At some point I decided to try out RSA using manageable primes and a very short message. This can be done using a calculator, without programming. However, I used Delphi (Object Pascal) for this study. Delphi and its successors are fine products, but... I have encountered frustration when porting something from an older version to a more recent one. The “encryption studies” Delphi project included some components that are not supported in Embarcadero XE2 and later versions. In practical terms that means I have to drag the old computer from the closet--or lift it, which is worse--and fire up Delphi in order to verify my memory about this part of my story.

The old computer has something wrong on the motherboard--not the battery, which I replaced. It needs to be “charged up” for a while before it will boot. That is why I am including this irrelevant information. It is charging as I write.

OK, got it! Had to copy a .dll from the old computer to the folder where the “encryption studies” executable is stored on my current working computer. This problem could probably have been avoided by compiling the .dll into the executable to begin with.

Strictly speaking, the key should be longer than the test message. However, the idea should be clear enough, if the demonstration is a little sloppy.

The demonstration (bottom right of form) consists of numbered steps. Each step has an associated button except step 3, in which the test message is entered.

For the illustration on the left, I clicked the step 1 and step 2 buttons in turn, to compute R and phi(R), and then to generate suitable values n and m whose product is congruent to 1 (mod phi(R)).

A default test message is shown in step 3. Note that to compute phi(R) (the number of numbers between 1 and R − 1 that are relatively prime to R) requires knowledge of the factors of R. phi(R) = (P − 1) ∙ (Q − 1).

Step 4 encodes the message using the public key R and n. While the message is decoded using the private key R and m in the final step.

Many superior explanations of public key encryption may be found on the Internet, some including simple computational examples. One approach to enhancing understanding, as illustrated here, is to program the computations that make up the steps of the algorithm, bearing in mind that real-world applications of public key encryption require much larger numbers (such that R is not factorable by ordinary means) and hence more sophisticated computational methods.

One final remark... If I ever travel on the Trans-Siberian Railway from Moscow to Vladivostok, I will leave all this stuff at home--won’t need it anyway, because my sweetheart will be with me.

[1] http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pretty_Good_Privacy

[2] http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/One-time_pad

[3] Machine settings were sometimes guessable and sometimes reused.

[4] Reprinted in: Martin Gardner, Penrose Tiles to Trapdoor Ciphers (W. H. Freeman, 1989).

[5] http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Shor’s_algorithm