Playing the odds:

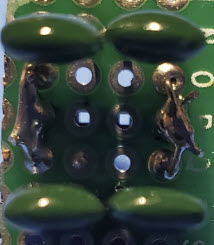

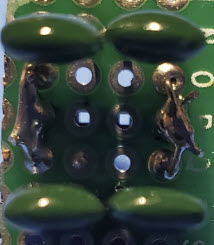

Suppose that four capacitors are randomly selected from a batch marked

1 nF at 10%, and are connected in series-parallel to make a circuit

having

the same 1 nF capacitance, as illustrated above. What would be the

appropriate tolerance designation for the 4-capacitor circuit? If the

individual capacitors are all 1 nF then the circuit capacitance is also

1 nF, but the σ value for a hypothetical batch of 4-capacitor circuits

will be the standard

error of the mean, denoted σm. To compute this

statistic, divide σ by √N. In this case N is 4 and √4 is 2 so σm

= σ/2. As previously noted, tolerance corresponds to 3σ

(i.e., tolerance is proportional to σ), which means that the tolerance

of the 4-capacitor circuit is the constituent capacitor tolerance

divided by 2, which in the example would be 5%. It is possible to

iterate the idea, so that 16 capacitors similarly configured would make

a circuit with 2.5% tolerance, and so forth, but that would be

silly—better to spend a dollar for a 1% capacitor.

Playing the odds:

Suppose that four capacitors are randomly selected from a batch marked

1 nF at 10%, and are connected in series-parallel to make a circuit

having

the same 1 nF capacitance, as illustrated above. What would be the

appropriate tolerance designation for the 4-capacitor circuit? If the

individual capacitors are all 1 nF then the circuit capacitance is also

1 nF, but the σ value for a hypothetical batch of 4-capacitor circuits

will be the standard

error of the mean, denoted σm. To compute this

statistic, divide σ by √N. In this case N is 4 and √4 is 2 so σm

= σ/2. As previously noted, tolerance corresponds to 3σ

(i.e., tolerance is proportional to σ), which means that the tolerance

of the 4-capacitor circuit is the constituent capacitor tolerance

divided by 2, which in the example would be 5%. It is possible to

iterate the idea, so that 16 capacitors similarly configured would make

a circuit with 2.5% tolerance, and so forth, but that would be

silly—better to spend a dollar for a 1% capacitor.

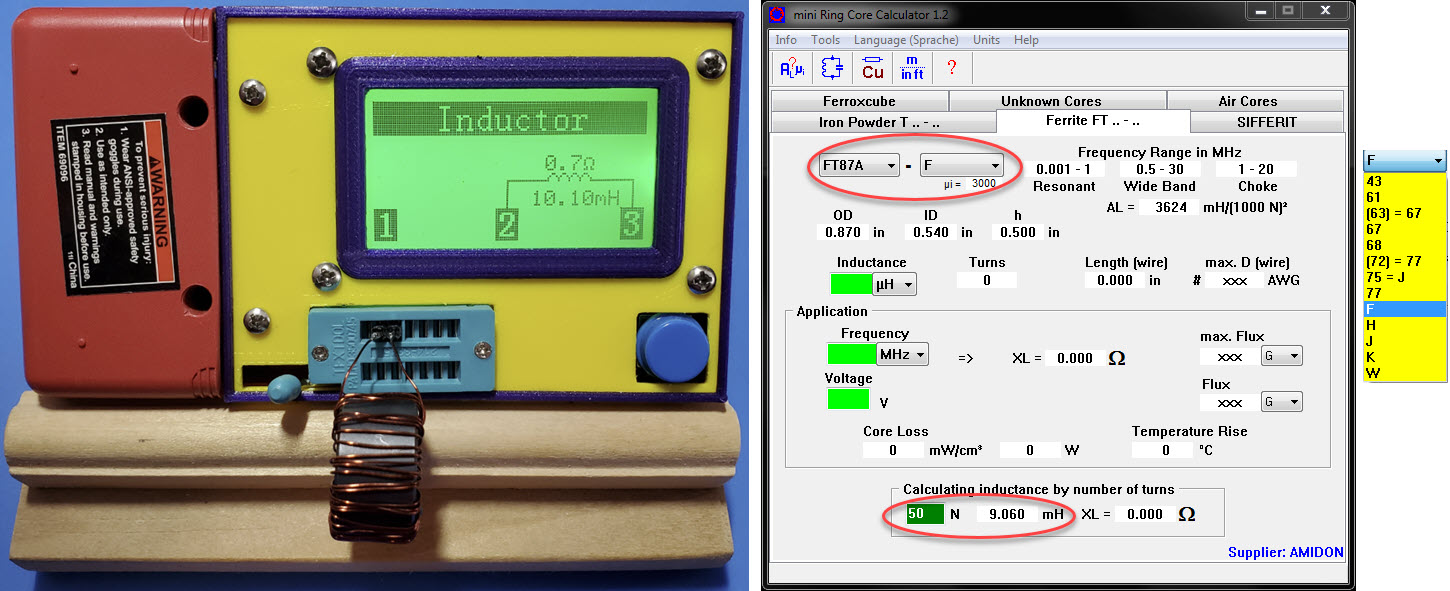

Measurement

torture:

While mildly interesting as a path to improving the precision of a

measurement, the preceding was of

no use in figuring out the unyielding FT87A mix problem.

Frequency measurements were the same to 2 or 3 significant digits,

whether a

single-capacitor was used for the tank circuit, or four. While in the

midst of this perseverative exercise,

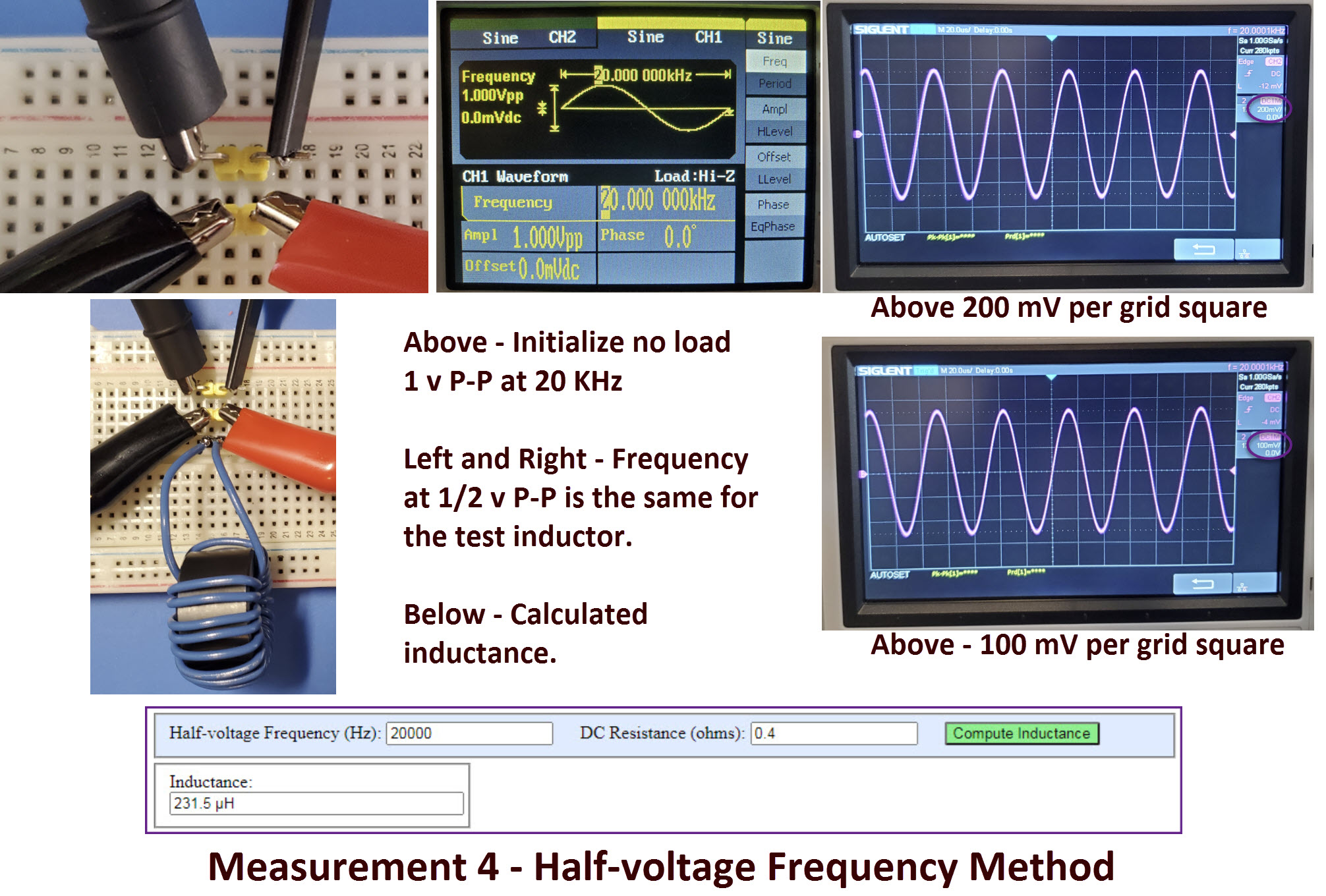

I recalled another method of determining inductance, the half-voltage frequency method, for

which I had made a convenience

calculator.

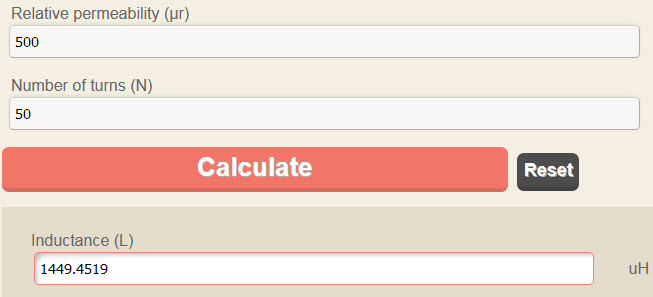

This recollection caused me to think about one of the assumptions of

the method, namely that the function generator’s output impedance is 50

ohms. The Siglent generator that I was using has the requisite output

impedance (photo left), but I wasn't sure of the attached cable, which

had been changed from the manufacturer-supplied cable at some point in

the past, so I replaced the output cable with a known 50-ohm impedance

lead.

Measurement

torture:

While mildly interesting as a path to improving the precision of a

measurement, the preceding was of

no use in figuring out the unyielding FT87A mix problem.

Frequency measurements were the same to 2 or 3 significant digits,

whether a

single-capacitor was used for the tank circuit, or four. While in the

midst of this perseverative exercise,

I recalled another method of determining inductance, the half-voltage frequency method, for

which I had made a convenience

calculator.

This recollection caused me to think about one of the assumptions of

the method, namely that the function generator’s output impedance is 50

ohms. The Siglent generator that I was using has the requisite output

impedance (photo left), but I wasn't sure of the attached cable, which

had been changed from the manufacturer-supplied cable at some point in

the past, so I replaced the output cable with a known 50-ohm impedance

lead.

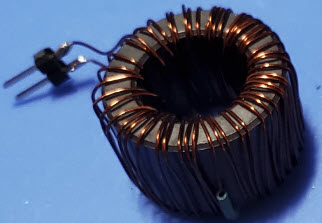

Fresh

start:

In one sense starting over is just

another kind of perseveration, but I was curious if the FT87A might

have an inconspicuous marking on it, maybe in the middle somewhere

(obscured by the coil). Also the 50-turn test coil was poorly wound,

loose, unevenly spaced. I

should make a better test coil. The most disturbing part of the

classification problem was not the failure of identifying the mix, but

rather the inconsistent results of measurements. Different methods of

measuring the same thing, whether the thing being measured is length or

weight or inductance, should yield the same approximate

answer.

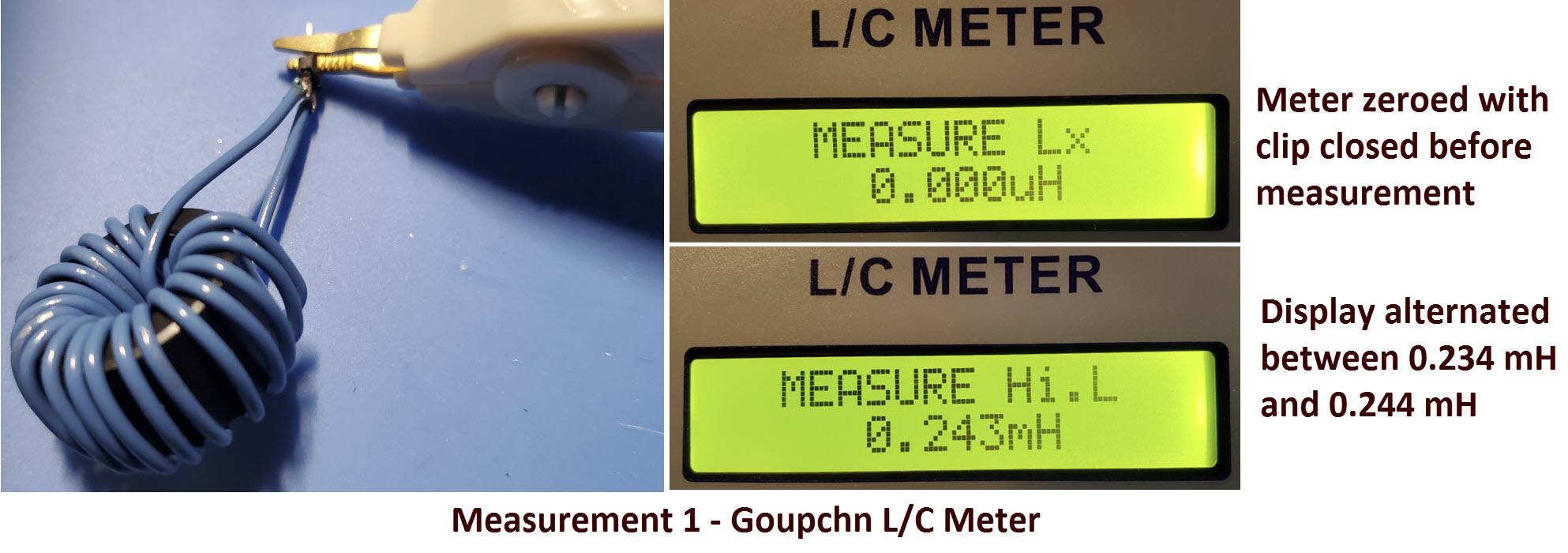

Stripped of its first test coil, the

ferrite toroid had no hidden inscription on either outside or inside,

and was just one shade of

grey! The chance of its having an identifying mark was a long shot, of

course. For the next suite of tests with this toroid I

wound 20 turns of plastic insulated wire, somewhat more neatly than the

enamel-insulated wire coil had been wound. The plan was to measure the

new coil’s inductance in four different ways, while recording details

at each step. Snapping a cellphone photo at each step is one way to

temper haste.

Stripped of its first test coil, the

ferrite toroid had no hidden inscription on either outside or inside,

and was just one shade of

grey! The chance of its having an identifying mark was a long shot, of

course. For the next suite of tests with this toroid I

wound 20 turns of plastic insulated wire, somewhat more neatly than the

enamel-insulated wire coil had been wound. The plan was to measure the

new coil’s inductance in four different ways, while recording details

at each step. Snapping a cellphone photo at each step is one way to

temper haste.

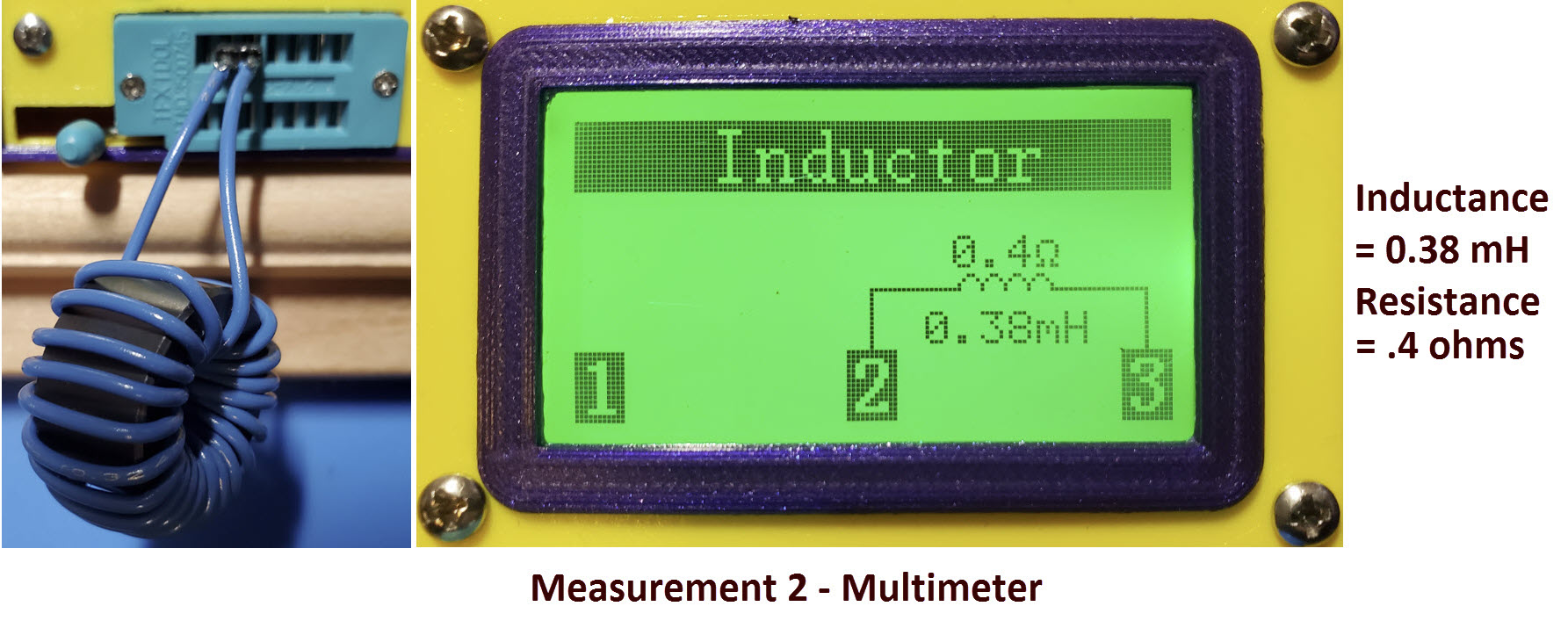

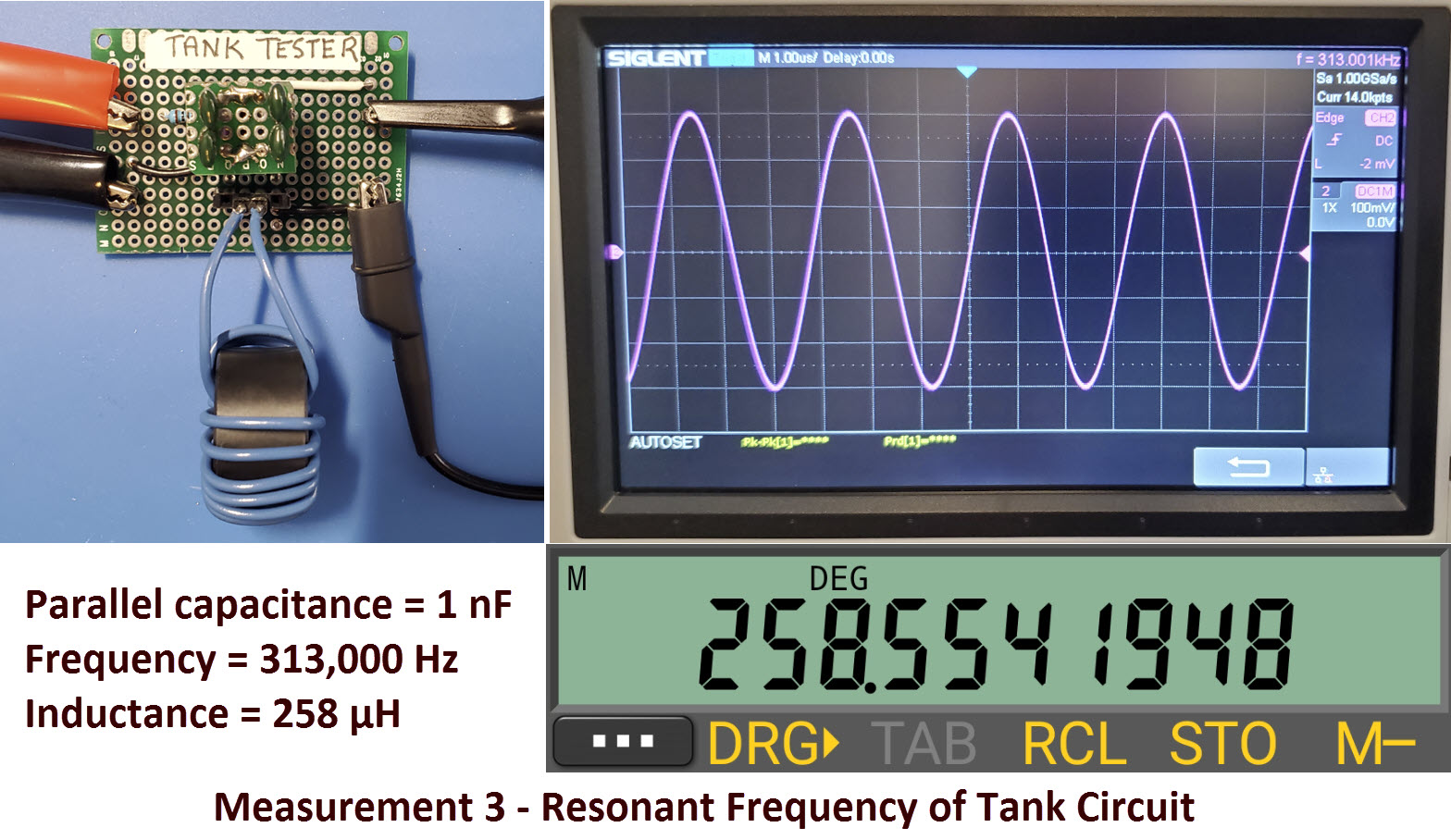

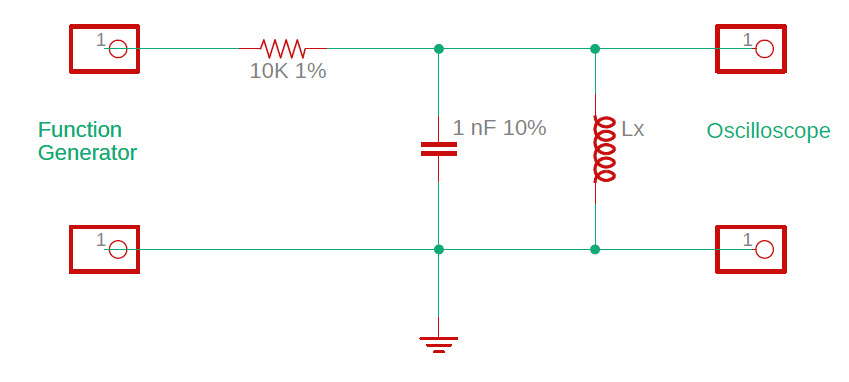

The four measurement procedures can be summarized as 1) Goupchn L/C

meter direct measurement, 2) Multi-meter measurement, 3) Tank circuit

resonant frequency determination, and 4) Half-voltage frequency

measurement. The following is a picture story.

Four Measurements of

Inductance

What is

it?

What is

it? What is

it?

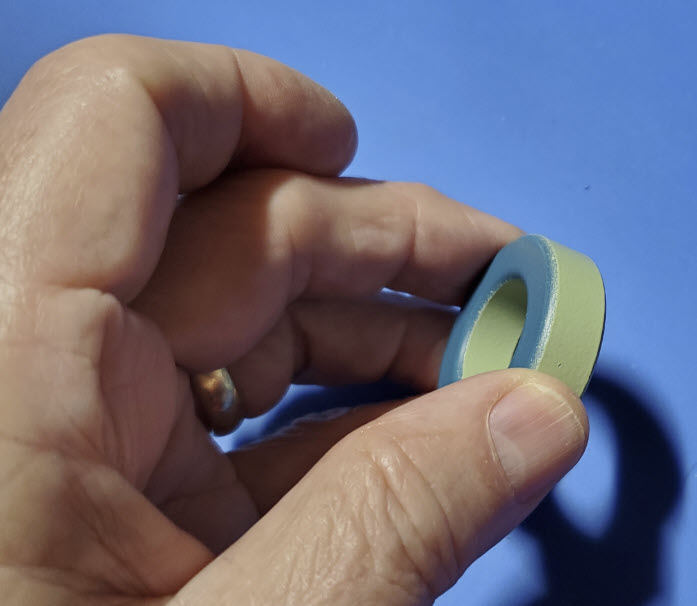

A few years ago at a

hamfest I

bought a

handful of identical blue green toroids—I think the investment was $3

for the

lot. Colored toroids are iron powder mixtures, while grey or blackish

ones are ferrite toroids. However, at the time of this purchase I knew

almost

nothing

about the

different sizes, shapes, mixtures, or their physical and electronic

properties. At first I imagined that the colors were a simple code that

would lead to quick and easy identification of relevant electronic

properties. The resistor color code (by analogy) follows the order of

colors in the visible light spectrum, which makes it easy to identify a

marked resistor value quickly. Iron powder toroid colors are also

a code. However, toroid colors are

not as straightforward to read and interpret as resistor bands are.

This led to an

interesting study.

What is

it?

A few years ago at a

hamfest I

bought a

handful of identical blue green toroids—I think the investment was $3

for the

lot. Colored toroids are iron powder mixtures, while grey or blackish

ones are ferrite toroids. However, at the time of this purchase I knew

almost

nothing

about the

different sizes, shapes, mixtures, or their physical and electronic

properties. At first I imagined that the colors were a simple code that

would lead to quick and easy identification of relevant electronic

properties. The resistor color code (by analogy) follows the order of

colors in the visible light spectrum, which makes it easy to identify a

marked resistor value quickly. Iron powder toroid colors are also

a code. However, toroid colors are

not as straightforward to read and interpret as resistor bands are.

This led to an

interesting study. Inches:

The world is metric but for some reason, toroid classification uses

inch measure. First there is an alpha prefix, ‘T’ for toroid and

‘FT’ for guess what. After that comes a number that seems mysterious,

until we learn that it is the outer diameter of the annulus in

hundredths of

an inch.

Thus the blue-green toroid in the illustration is a T157-something

because first,

it is an iron powder (not ferrite) toroid and second, its outer

diameter is 1.57 inches.

Luckily it is not necessary to be

able to measure the diameter to the precision of one-hundredth of

an inch, because the next smaller iron powder toroid is 1.30 inches and

the next larger one is 1.84 inches—according to the mini Ring Core calculator (a

useful and free utility).

Inches:

The world is metric but for some reason, toroid classification uses

inch measure. First there is an alpha prefix, ‘T’ for toroid and

‘FT’ for guess what. After that comes a number that seems mysterious,

until we learn that it is the outer diameter of the annulus in

hundredths of

an inch.

Thus the blue-green toroid in the illustration is a T157-something

because first,

it is an iron powder (not ferrite) toroid and second, its outer

diameter is 1.57 inches.

Luckily it is not necessary to be

able to measure the diameter to the precision of one-hundredth of

an inch, because the next smaller iron powder toroid is 1.30 inches and

the next larger one is 1.84 inches—according to the mini Ring Core calculator (a

useful and free utility).

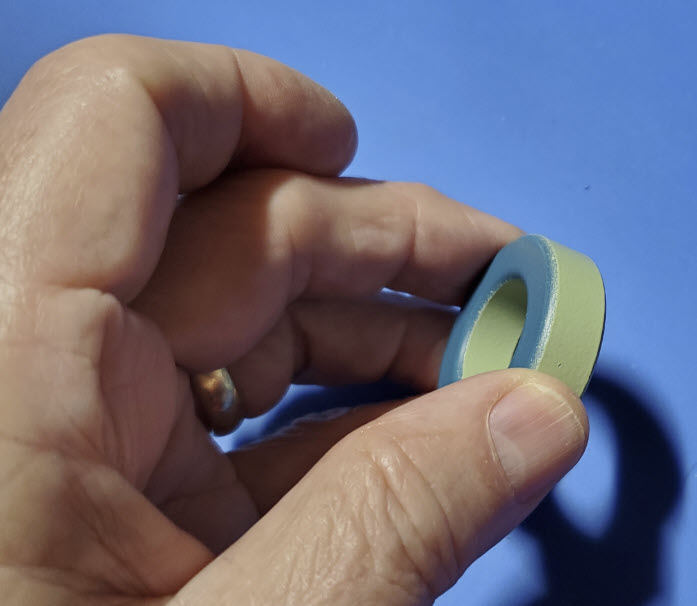

Ferrite

Toroid:

One of the ferrite toroids in my ‘collection’ has an unusual shape. It

is fatter than most, relative to its diameter. This dimension is

called ‘height’ not width. (For naming this dimension, toroids must

be

imagined lying flat, not in the orientation of a car wheel.)

Ferrite

Toroid:

One of the ferrite toroids in my ‘collection’ has an unusual shape. It

is fatter than most, relative to its diameter. This dimension is

called ‘height’ not width. (For naming this dimension, toroids must

be

imagined lying flat, not in the orientation of a car wheel.)

One

more: I will present one more example, partly because the

toroid is pretty, but also because, for this one, two mix types yield

very similar calculated inductance values; thus correct classification

depends on its color code.

One

more: I will present one more example, partly because the

toroid is pretty, but also because, for this one, two mix types yield

very similar calculated inductance values; thus correct classification

depends on its color code.

Units are Hertz,

Farads, and Henrys, so there are several 10-something

terms in the calculation. Being careful with the decimal point and

using 423 KHz as the

resonant frequency (the measured value), and 1 nF (10-9

F) for capacitance (its marked and weakly measured value), yields a

calculated inductance of

141.5 μH. This value compares favorably with the multi-tester 0.14 mH

result.

Units are Hertz,

Farads, and Henrys, so there are several 10-something

terms in the calculation. Being careful with the decimal point and

using 423 KHz as the

resonant frequency (the measured value), and 1 nF (10-9

F) for capacitance (its marked and weakly measured value), yields a

calculated inductance of

141.5 μH. This value compares favorably with the multi-tester 0.14 mH

result.

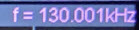

There were three possibilities for the anticipated outcome of the

resonant frequency test: 1) confirm the original multi-meter result, 2)

confirm the Goupchn meter reading, or 3) ‘none of the above’. Using the

same 1 nF capacitor (same tank circuit) as before, the resonant

frequency was found to be 130 KHz. From this measurement the calculated

inductance is 1.5 mH, which confirms (approximately) the Goupchn

reading.

There were three possibilities for the anticipated outcome of the

resonant frequency test: 1) confirm the original multi-meter result, 2)

confirm the Goupchn meter reading, or 3) ‘none of the above’. Using the

same 1 nF capacitor (same tank circuit) as before, the resonant

frequency was found to be 130 KHz. From this measurement the calculated

inductance is 1.5 mH, which confirms (approximately) the Goupchn

reading.

Playing the odds:

Suppose that four capacitors are randomly selected from a batch marked

1 nF at 10%, and are connected in series-parallel to make a circuit

having

the same 1 nF capacitance, as illustrated above. What would be the

appropriate tolerance designation for the 4-capacitor circuit? If the

individual capacitors are all 1 nF then the circuit capacitance is also

1 nF, but the σ value for a hypothetical batch of 4-capacitor circuits

will be the standard

error of the mean, denoted σm. To compute this

statistic, divide σ by √N. In this case N is 4 and √4 is 2 so σm

= σ/2. As previously noted, tolerance corresponds to 3σ

(i.e., tolerance is proportional to σ), which means that the tolerance

of the 4-capacitor circuit is the constituent capacitor tolerance

divided by 2, which in the example would be 5%. It is possible to

iterate the idea, so that 16 capacitors similarly configured would make

a circuit with 2.5% tolerance, and so forth, but that would be

silly—better to spend a dollar for a 1% capacitor.

Playing the odds:

Suppose that four capacitors are randomly selected from a batch marked

1 nF at 10%, and are connected in series-parallel to make a circuit

having

the same 1 nF capacitance, as illustrated above. What would be the

appropriate tolerance designation for the 4-capacitor circuit? If the

individual capacitors are all 1 nF then the circuit capacitance is also

1 nF, but the σ value for a hypothetical batch of 4-capacitor circuits

will be the standard

error of the mean, denoted σm. To compute this

statistic, divide σ by √N. In this case N is 4 and √4 is 2 so σm

= σ/2. As previously noted, tolerance corresponds to 3σ

(i.e., tolerance is proportional to σ), which means that the tolerance

of the 4-capacitor circuit is the constituent capacitor tolerance

divided by 2, which in the example would be 5%. It is possible to

iterate the idea, so that 16 capacitors similarly configured would make

a circuit with 2.5% tolerance, and so forth, but that would be

silly—better to spend a dollar for a 1% capacitor. Measurement

torture:

While mildly interesting as a path to improving the precision of a

measurement, the preceding was of

no use in figuring out the unyielding FT87A mix problem.

Frequency measurements were the same to 2 or 3 significant digits,

whether a

single-capacitor was used for the tank circuit, or four. While in the

midst of this perseverative exercise,

I recalled another method of determining inductance, the half-voltage frequency method, for

which I had made a convenience

calculator.

This recollection caused me to think about one of the assumptions of

the method, namely that the function generator’s output impedance is 50

ohms. The Siglent generator that I was using has the requisite output

impedance (photo left), but I wasn't sure of the attached cable, which

had been changed from the manufacturer-supplied cable at some point in

the past, so I replaced the output cable with a known 50-ohm impedance

lead.

Measurement

torture:

While mildly interesting as a path to improving the precision of a

measurement, the preceding was of

no use in figuring out the unyielding FT87A mix problem.

Frequency measurements were the same to 2 or 3 significant digits,

whether a

single-capacitor was used for the tank circuit, or four. While in the

midst of this perseverative exercise,

I recalled another method of determining inductance, the half-voltage frequency method, for

which I had made a convenience

calculator.

This recollection caused me to think about one of the assumptions of

the method, namely that the function generator’s output impedance is 50

ohms. The Siglent generator that I was using has the requisite output

impedance (photo left), but I wasn't sure of the attached cable, which

had been changed from the manufacturer-supplied cable at some point in

the past, so I replaced the output cable with a known 50-ohm impedance

lead.

Stripped of its first test coil, the

ferrite toroid had no hidden inscription on either outside or inside,

and was just one shade of

grey! The chance of its having an identifying mark was a long shot, of

course. For the next suite of tests with this toroid I

wound 20 turns of plastic insulated wire, somewhat more neatly than the

enamel-insulated wire coil had been wound. The plan was to measure the

new coil’s inductance in four different ways, while recording details

at each step. Snapping a cellphone photo at each step is one way to

temper haste.

Stripped of its first test coil, the

ferrite toroid had no hidden inscription on either outside or inside,

and was just one shade of

grey! The chance of its having an identifying mark was a long shot, of

course. For the next suite of tests with this toroid I

wound 20 turns of plastic insulated wire, somewhat more neatly than the

enamel-insulated wire coil had been wound. The plan was to measure the

new coil’s inductance in four different ways, while recording details

at each step. Snapping a cellphone photo at each step is one way to

temper haste.