OR (the long way)

It’s funny how we hit upon new things in

roundabout ways. Some random thought prompted me to do an Internet

search for ‘order finding’. Many of the search results related to

quantum computing and some of these mentioned a logic element called

the ‘Toffoli’ gate. Although I was familiar with the common logic gates

AND, OR, NOT, XOR, etc., I had never heard of Toffoli. At first I had

trouble remembering the name and how to spell it. Then I thought of

‘toffee’ and memorized that the name has two ‘f’s, two ‘O’s, and one

‘l’.

The Toffoli gate is sometimes also

called the C-C-gate, where the letter ‘C’ stands for the word

‘controlled’. However, I will stick with ‘Toffoli’ in this story. It is

easy to understand the specific logic function that the Toffoli gate

performs. The gate has three inputs, which are typically labelled A, B,

and C.

It also has three outputs, whereas common ordinary logic gates have one

output. Toffoli outputs may similarly be labelled P, Q, and R. The

interesting one

is R, because P=A and Q=B, by definition. Output R is like an inverter

(logical NOT), except that it only inverts the C input if both A and B

are true.

In shorthand R = not C if both A and B are true; otherwise R

= C. This statement can be expressed in a simple mathematical way, but

is easier

to understand in words, I think.

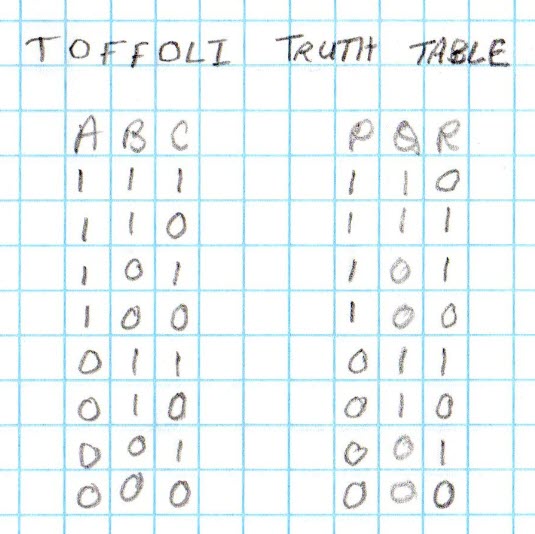

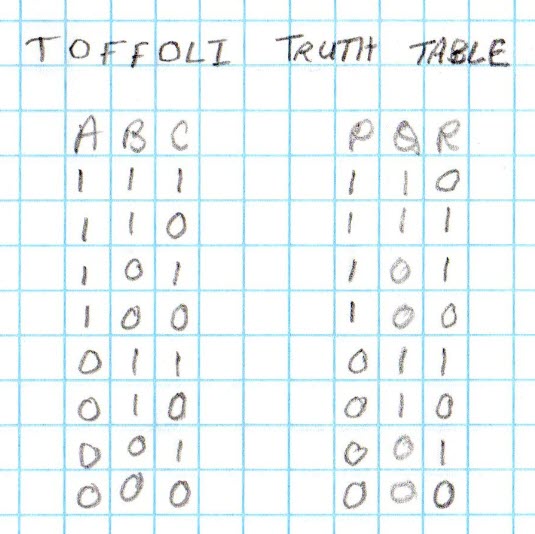

In the table reproduced above, ‘1’

stands for true

and ‘0’ for false,

as is the usual convention. (Similarly, in

electronic logic circuits, + is usually true, and – is false.) Notice

that in the first two rows, both A and B are true and R is not

C, while

in the remaining rows either A or B or both are false, and R = C.

The reason Toffoli gates are of interest

to scientists is due to a property that I will gloss over. They are

invertible. If you know the outputs, you can deduce what the inputs

are. This feature is not shared by some ordinary gates. For example, if

the output of an AND gate is true,

you know all the inputs must have

been true,

but if the output is false,

you cannot deduce which inputs

were false,

since any one of them being false

would render the output

false. One

is inclined to think that of course the Toffoli gate is

invertible, because of the cheat that copies A and B inputs to the P

and Q outputs. That is true, but in the quantum world things are messy,

and

since I don’t understand that world I will have to take the scientists’

word for how being invertible causes entropy to increase, and is

otherwise a commendable thing.

A second crucial property ensures the

Toffoli gate’s interest to researchers: ANY logic

function can be expressed as a combination of Toffoli gates! To prove

this statement it is only necessary to show that AND, OR, and NOT can

be so expressed. It has long been proven that any logic

function can be expressed as a function of these three elementary ones.

NOT is trivial, of course. Let ‘T’ stand for the Toffoli operator: not

C = T(1, 1, C). The other two are also easy, but require more

than one Toffoli gate to implement.

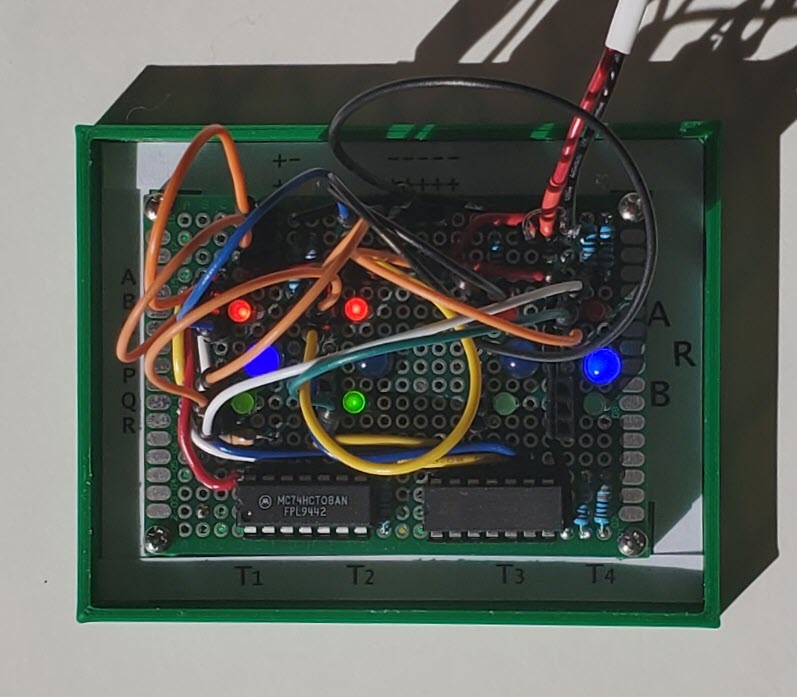

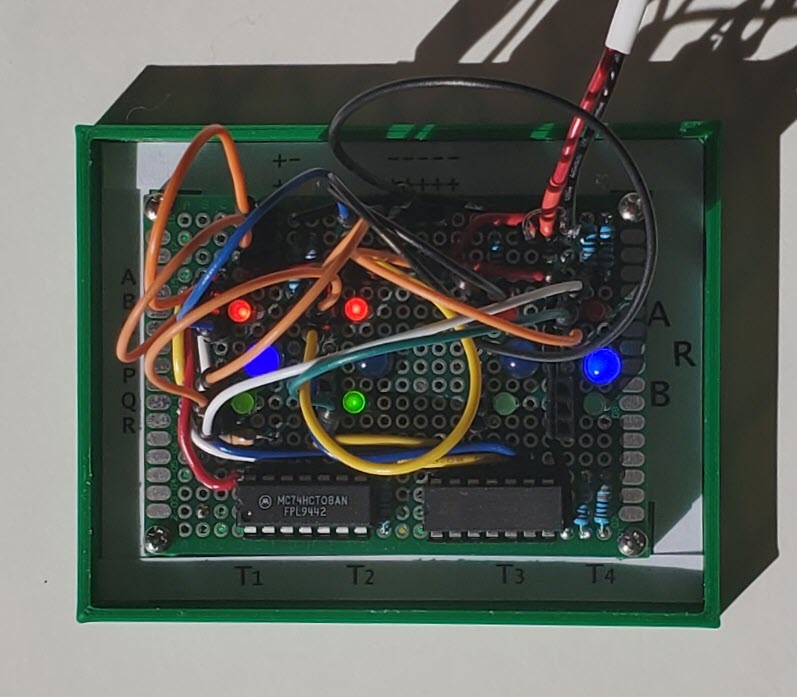

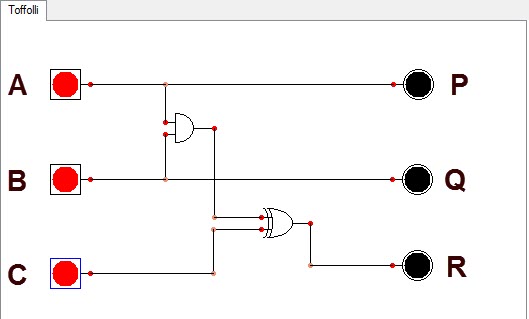

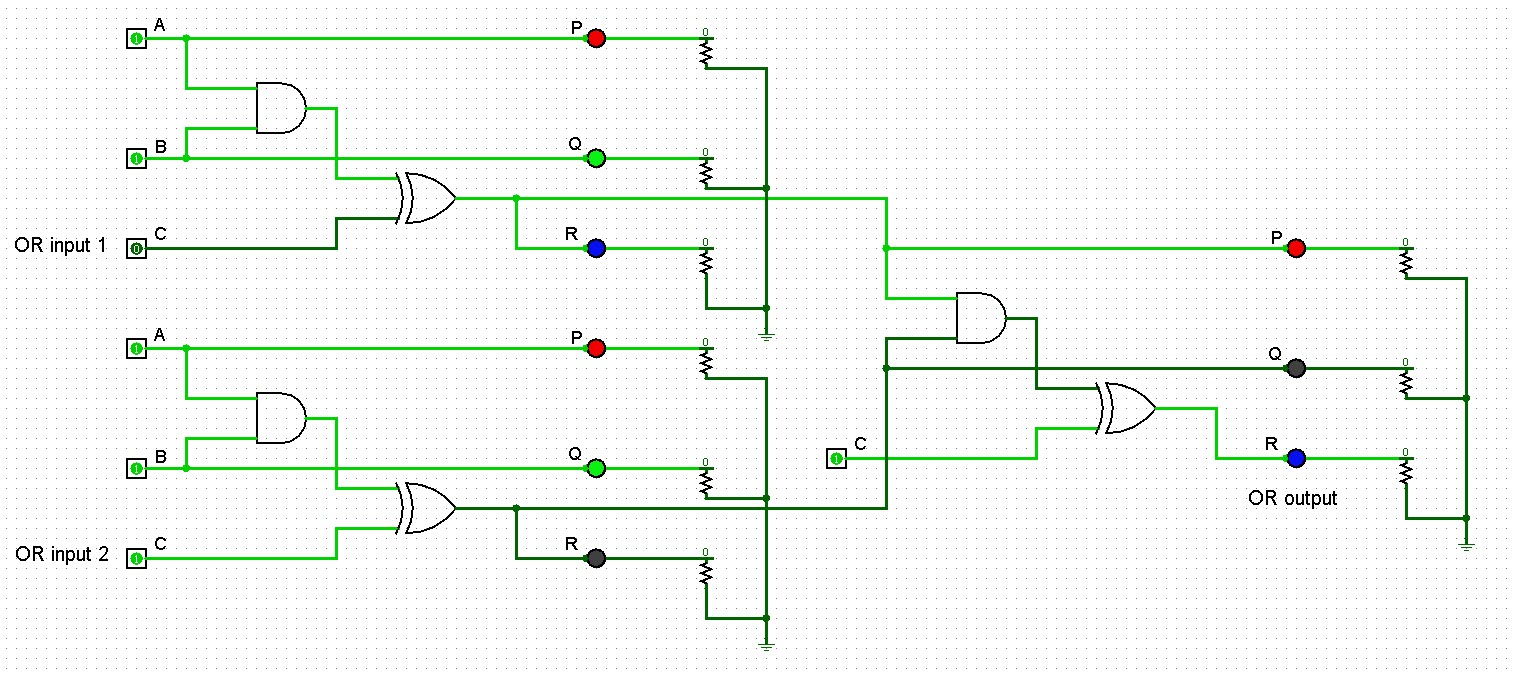

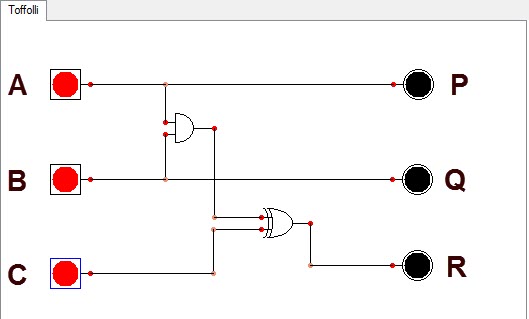

The Toffoli gate can be modelled

using ordinary gates. The Logic

Circuit Designer diagram

above depicts two gates AND (top left)

and XOR (bottom right), and their interconnections. [XOR means either A

or B but not both.] Now,

commonly available 2-input AND gates and 2-input XORs are packaged in

sets of

four. That is to say, each integrated circuit (chip) contains

four gates. So on contemplating the simple diagram above I thought of

assembling four Toffoli gates using just two ICs, with pin headers for

inputs and LEDs

to indicate both input and output states. The idea was that with four

gates

it would be possible to model an AND gate or an OR gate, in other words

to demonstrate the universality claim in an actual circuit.

Not long ago I asked a person who had

taught electronics in a technical college, what sorts of lab exercises

his

students were required to do as part of their coursework. His reply

surprised me. The labs

are all simulations. The students don’t solder anything, or even put

together breadboard circuits. They interact with

circuits using computer software, first constructing diagrams, and

afterward defining parameters that are needed to exercise the circuits,

the same as if they were real. —Logic circuits are particularly easy to

simulate (or so it seems). Pencil and paper suffice to trace logic

levels in simple circuits. They are just algebra, after all.

Logism

is a great (free) tool for designing and simulating logic circuits.

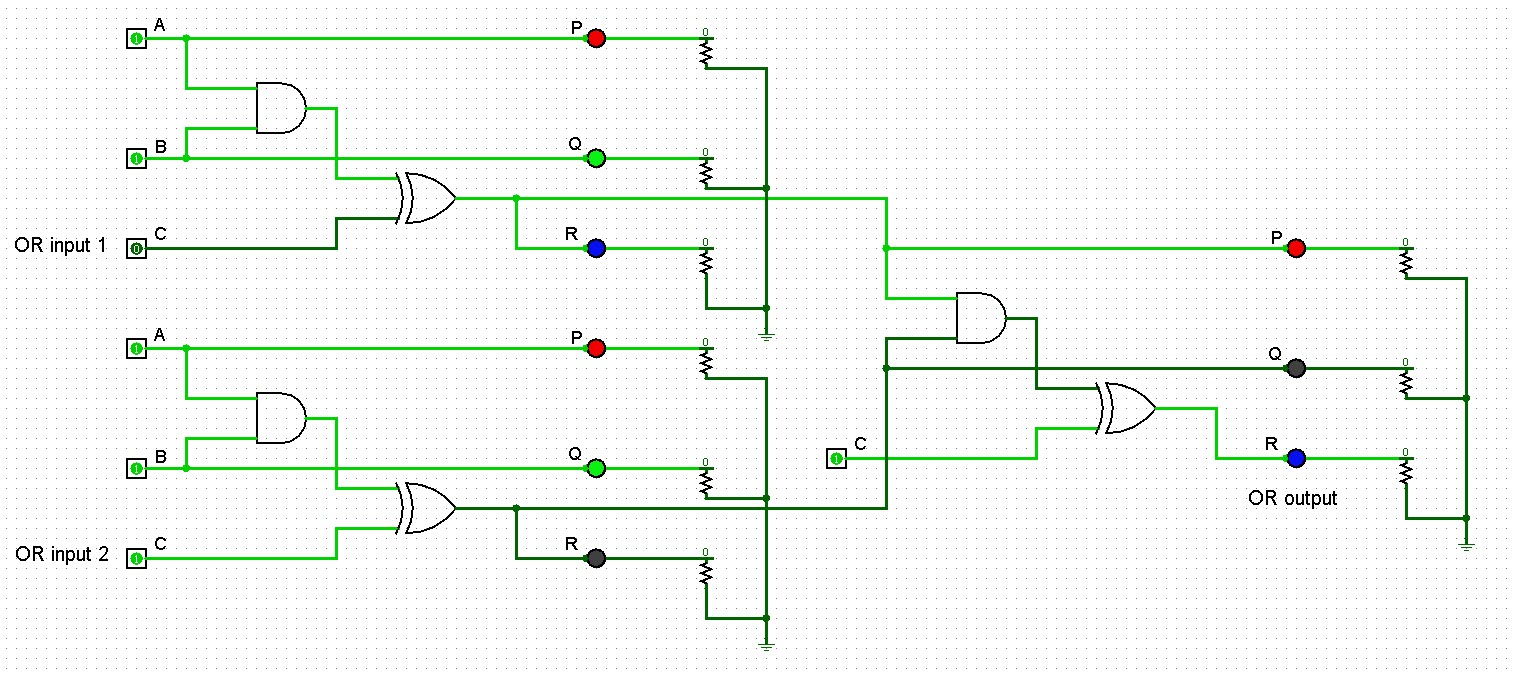

After diagramming one Toffoli gate with configurable inputs, it was

possible to copy/paste the composite diagram a couple of times, and

then connect the

three identical gates to function as a single 2-input OR gate. In the

illustration above, the first OR input is

set to false

(0), and the second to true

(1). The output is of course true

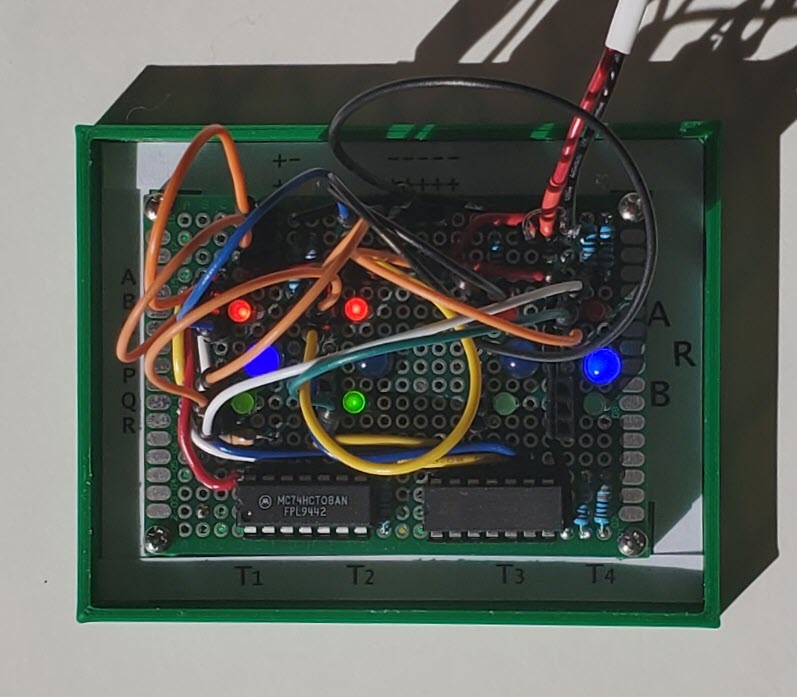

(rightmost blue LED). Now, I don’t mean to suggest that a physical

demonstration is more persuasive than the corresponding Logism

simulation, or more persuasive than working through the logic

expression with pencil and paper would be. It is not. However, the

photo at the top of this

page captures what is perhaps a more vivid demonstration of the exact

same circuit as

in the Logism simulation. Even the LED colors are the same!

In the

photo, the third Toffoli gate from left is not involved. Its A, B,

and C inputs were set to false

(black plug-in wires) so that the indicator LEDs

for that gate would be OFF. Each of the two leftmost gates performs R =

T(1, 1, C) = ~C (not C). The final rightmost gate’s A and B inputs

receive

the R outputs of the first two gates, while the C input of this gate is

set to true

(1). If C1 represents input

variable a

and C2 represents variable b, the rightmost

gate preforms T(~a,

~b, 1),

which is the same as a

⋁ b.

Constructing the physical model was fun

but at the same time tedious, in part because I had selected a

prototype

circuit board that has only 24 × 18 holes. Several of the current

limiting resistors

had to be soldered on the underside of the board.

Similarly, about half the connecting wires are on the bottom. The

left IC (type 7408) consists of four AND gates and the right IC (type

7486)

contains four XORs. The four Toffoli gates are arranged in vertical

columns left to right. In each column the topmost 3-hole pin header

corresponds to the inputs A, B, C, and the bottom pin header to the

outputs P, Q, and R. Red LEDs indicate states of the A inputs;

green LEDs the states of B inputs; and blue LEDs (the larger ones)

indicate the ‘R’ output of each gate. Illuminated stands for true, and

not illuminated means false.

Just to be clear, ‘real’ Toffoli gates are not made from ordinary

TTL gates. Best I can tell they are combinations of quantum dots or

some other arcane

sub-microscopic thing. The physical model described above is

just that, a model. By connecting the leftmost blue and yellow wires,

inputs a (C1)

and b (C2),

alternately to 1 (+) and 0 (–) it is possible to demonstrate that in

every case the rightmost blue LED represents the logical OR of a and b, illuminating

when either a

or b or

both are true,

and remaining dark when both are false.

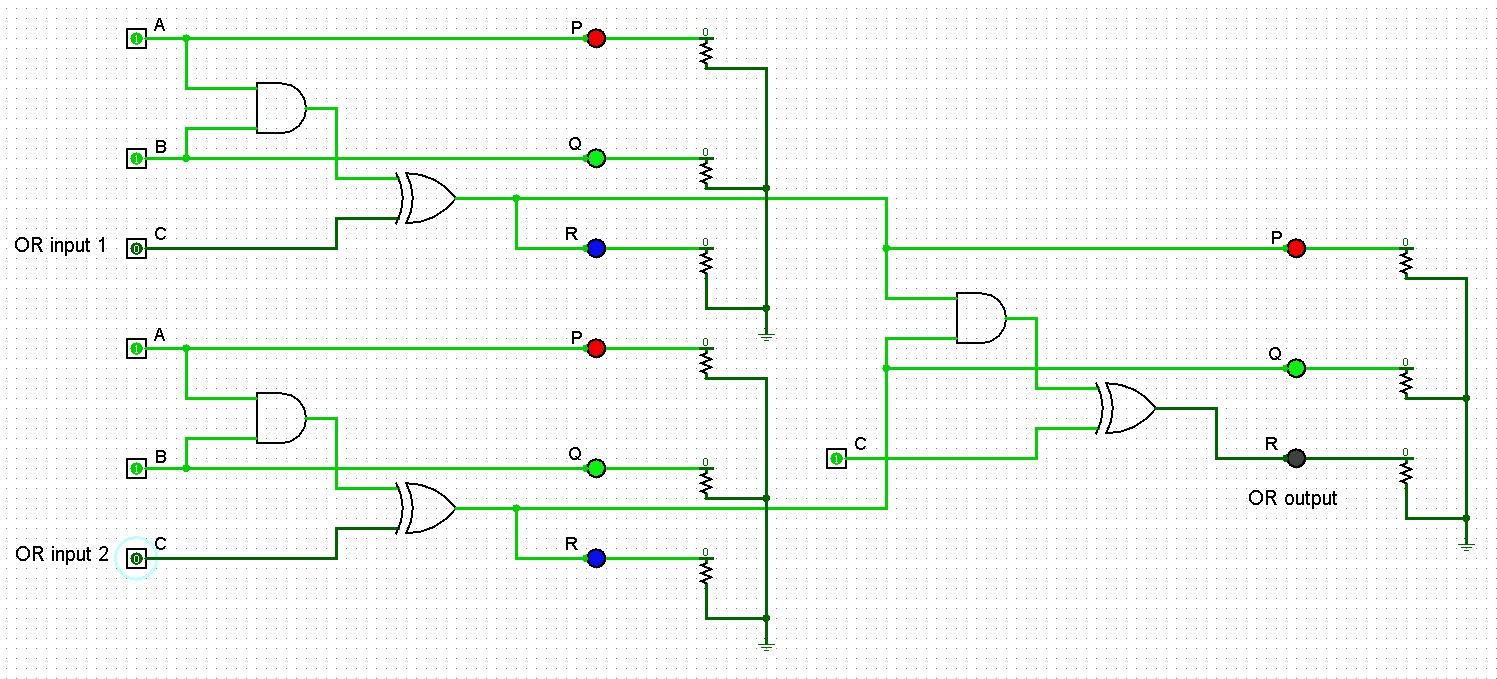

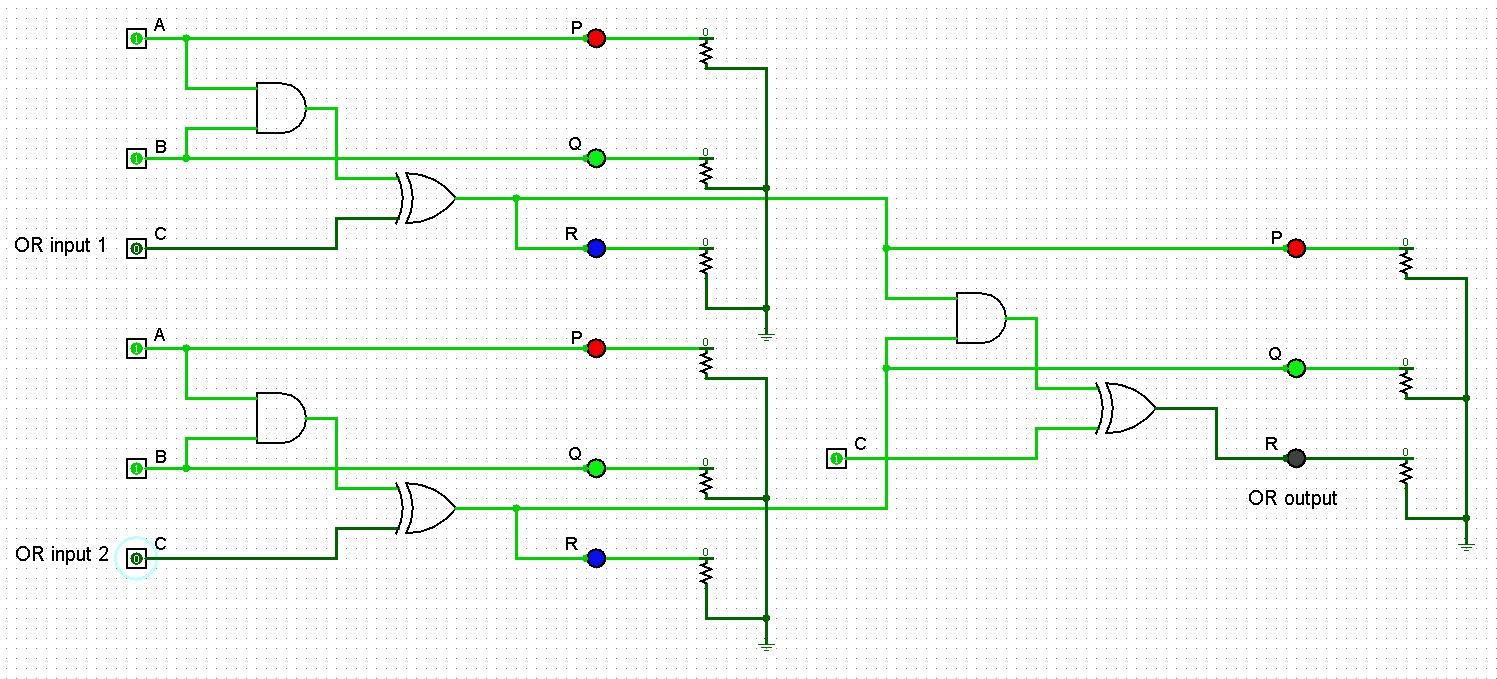

Of course, the

same is more easily demonstrated by toggling pins in Logism. In the

simulation below, both inputs are set to false, which causes

the OR output to be false,

in what surely seems a convoluted way.

Project descriptions on this page are intended for entertainment only.

The author makes no claim as to the accuracy or completeness of the

information presented. In no event will the author be liable for any

damages, lost effort, inability to carry out a similar project, or to

reproduce a claimed result, or anything else relating to a decision to

use the information on this page.