Oscilloscope Math Mode, tinySA Ultra RF power measurement, tinySA

signal generation, filter testing

These studies were prompted by a

remark from a respected source, claiming that an oscilloscope’s FFT1 function could

not be trusted for

measuring low pass filter parameters (in the HF regime). An

oscilloscope is not a spectrum analyzer. Would

selected

measurements with a consumer grade oscilloscope’s math

mode reveal inconsistencies, or otherwise call into question the

instrument’s accuracy or reliability?

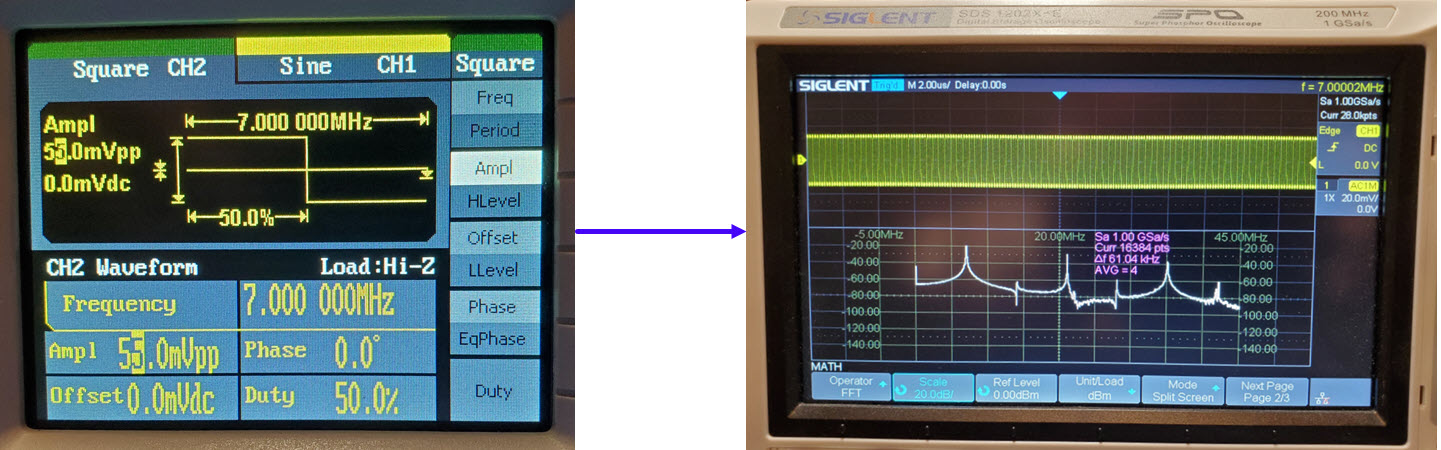

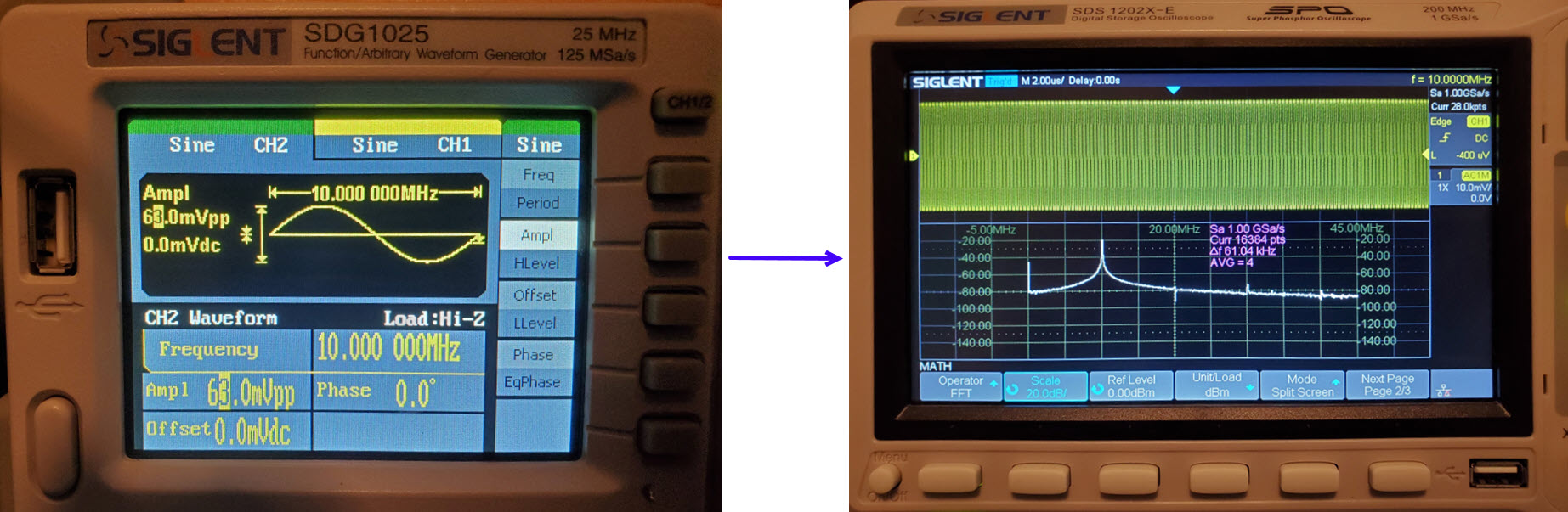

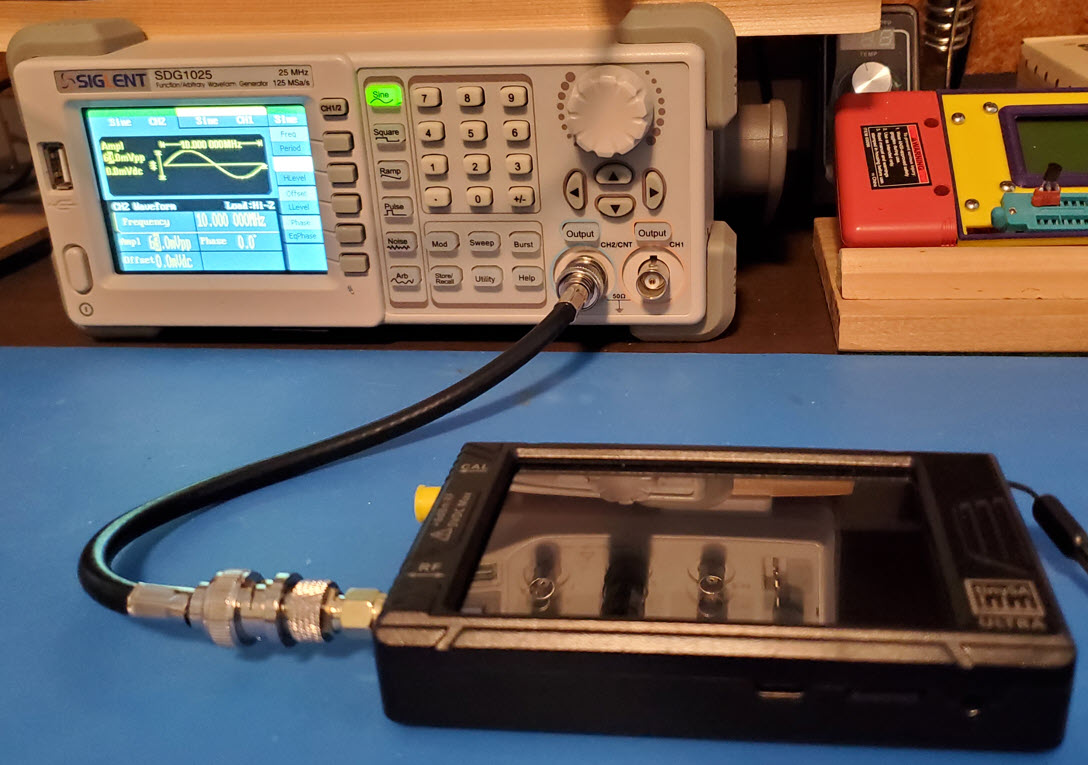

Exercise 1: The setup for this exercise is pictured above.

The Siglent signal generator’s output was jumpered directly to the

oscilloscope’s input using a short piece of 50 ohm coax terminated on

both ends with male BNCs. Three power levels: -10 dBm, -20 dBm, and -30

dBm were crossed with four frequencies: 5, 10, 15, and 20 MHz for

testing. In the illustration below, the signal generator is set to

produce a 10 MHz sine wave at 63 mV peak-to-peak. This output voltage

corresponds to

the -20

dBm power level at 50 ohms.2

It would be pointless to

reproduce a table of results, as the measurement for each power level

was the same as the stimulus power (output of function generator). Oscilloscope measured power at a given

source level did not vary across the 5 to 20 MHz test frequency range.3

Exercise 2:

Along with the advice not to rely on oscilloscope FFT

mode was an

alternative suggestion to use a spectrum analyzer, minimally an

inexpensive tinySA, for making filter measurements. This second exercise examines the tinySA

Ultra for the same

power × frequency values used in Exercise 1. The physical setup is

almost identical, except that a slightly longer length of coax was used,

and the spectrum analyzer end included a BNC-to-SMA adapter.

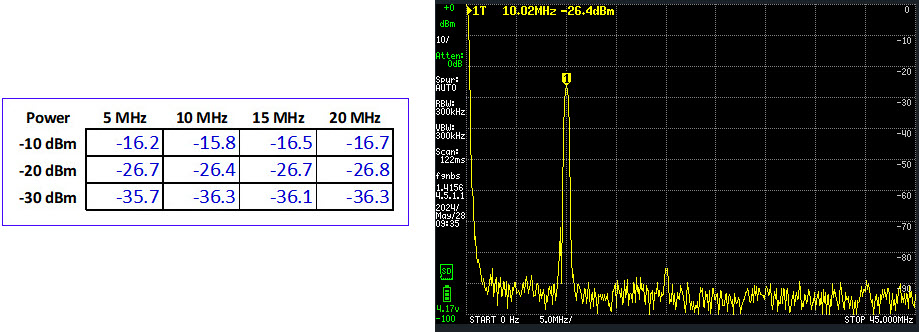

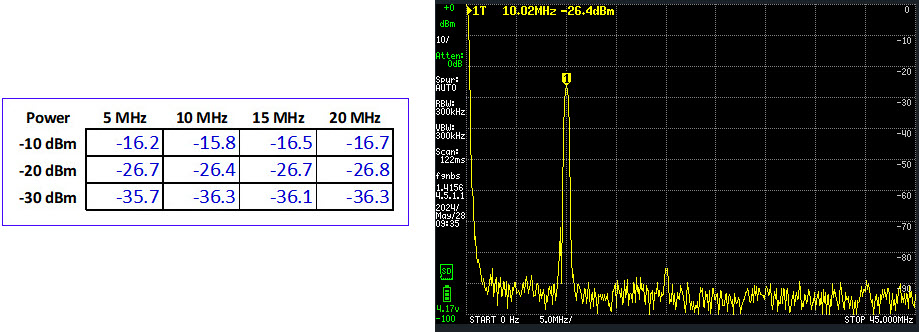

The same 12 measurements were carried

out using the

tinySA Ultra. It would be possible to dispense with a table of

measurements for this study as well. However, the illustration below

shows the values obtained for each combination of power and frequency,

as well as a screen capture of the representative 10 MHz at -20 dBm

signal as received by the tinySA Ultra. Measures averaged -6.35 dBm

from the stimulus power value. In other words, tinySA Ultra reported

the

signals to be consistently weaker than their programmed (and

oscilloscope-measured)

values by about 6⅓ dBm. Otherwise

measurements were consistent between power levels and across

frequencies.

Exercise 3:

The tinySA is two instruments in one. In addition to its spectrum

analyzer function the unit can also be used as a signal generator.

However, in that application it is limited a producing a sine wave

signal at a specified power level—It does not generate other waveforms,

as a function generator would. Nor is the output level as finely

adjustable as the bench instrument’s is.

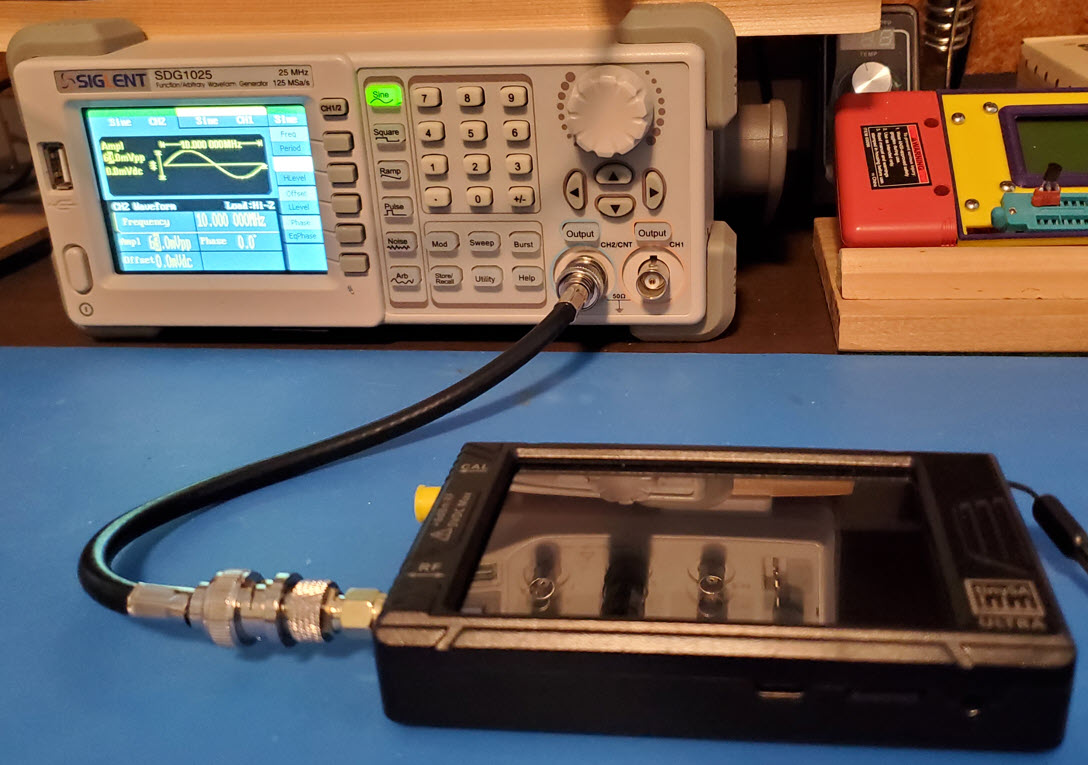

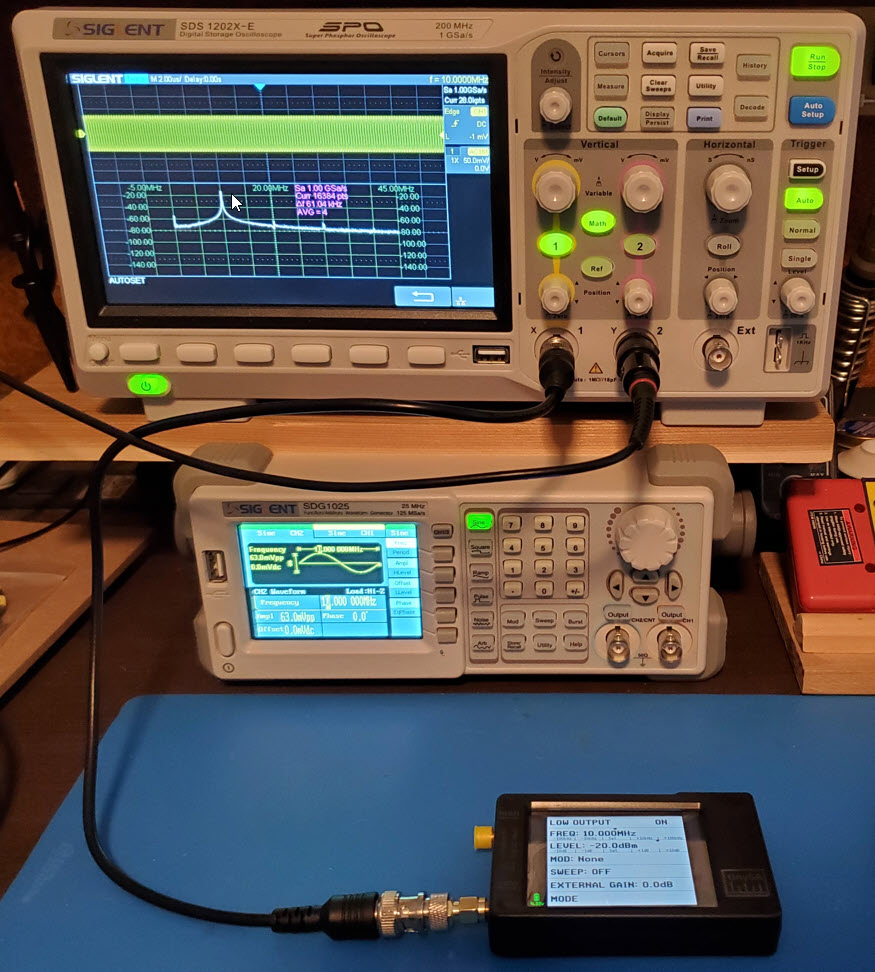

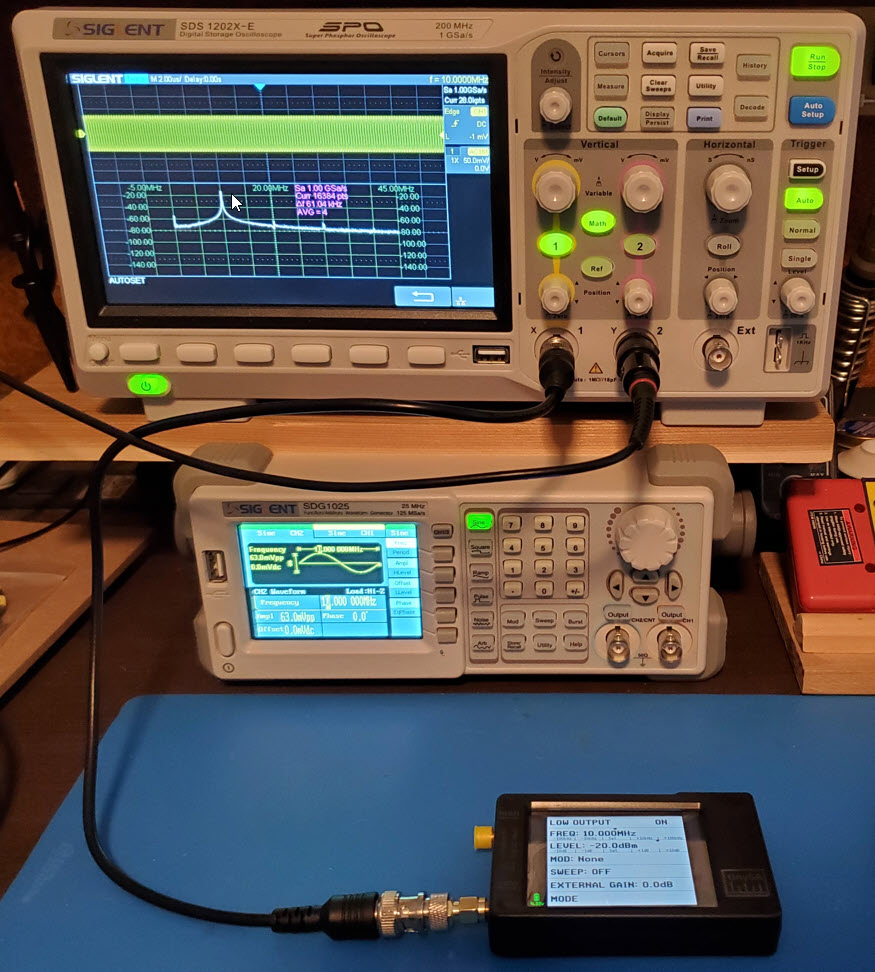

The photo above shows the setup for this

exercise. Although the bench function generator is powered-on, its

outputs are not connected and it is not involved in the exercise.

Instead, the tinySA is directly connected to the oscilloscope. Coax and

adapter are the same as in the previous exercise, but this is a

different tinySA, the basic model, not Ultra. It should be possible to

read test values from the photo. Output is a -20 dBm sine wave at 10

MHz. The oscilloscope trace reads above the -20 dBm grid line,

about ¼ up toward the 0 dBm reference level, which would make it about

-15 dBm. This is consistent with the previous exercise. Readings at the

other test frequencies were similarly around 5 to 6 dB stronger than

advertised. For example, here is the 15 MHz measure:

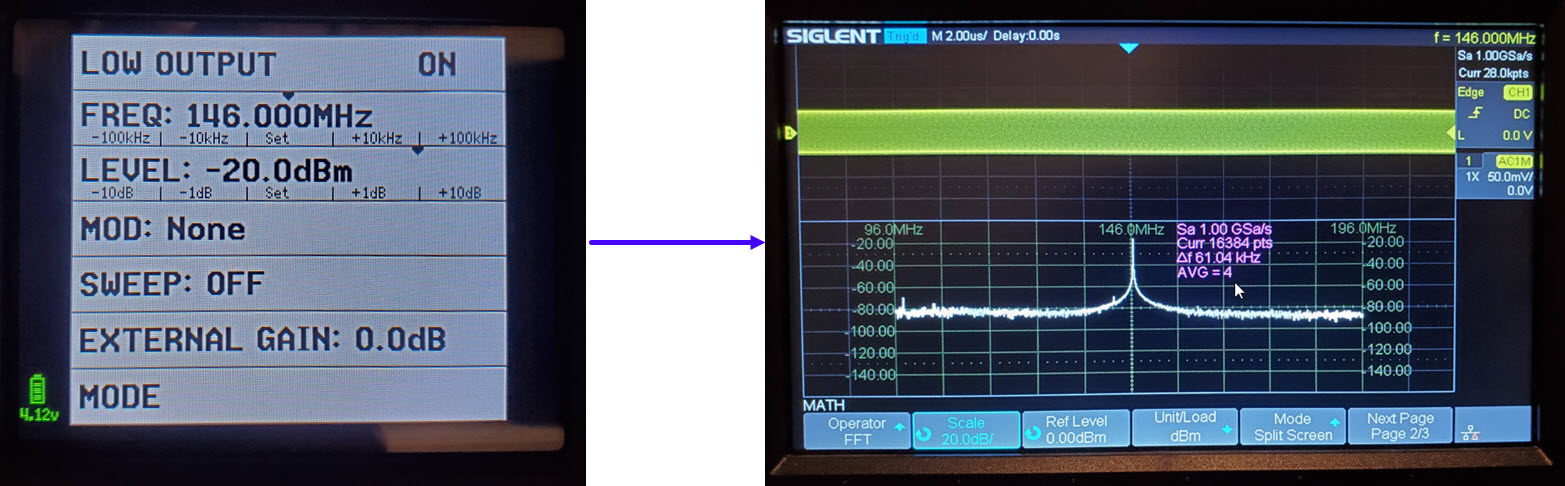

Although the tinySA is not as versatile as the bench

function generator, it has one capability that the Siglent instrument

lacks. tinySA can generate signals in the VHF and even UHF ranges while

the maximum frequency of the bench instrument is 25 MHz. I was curious

as to how the oscilloscope would fare in measuring the power of a 2

meter band signal. This was not an idle curiosity as I had carried out

some preliminary tests in the VHF domain, and was contemplating another.

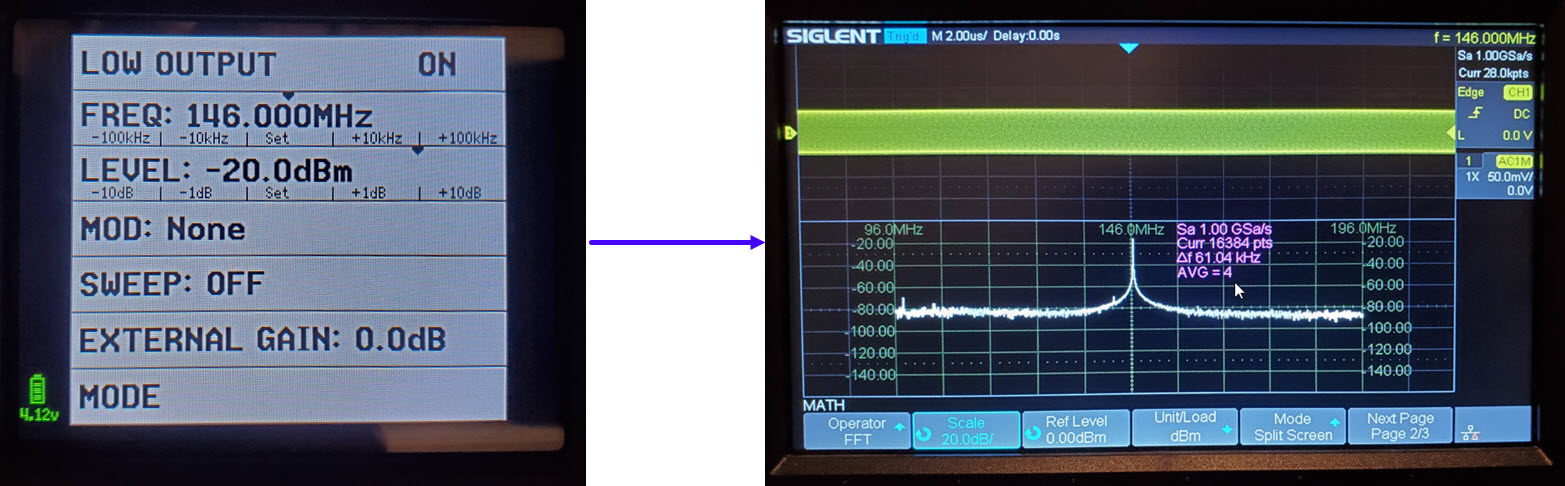

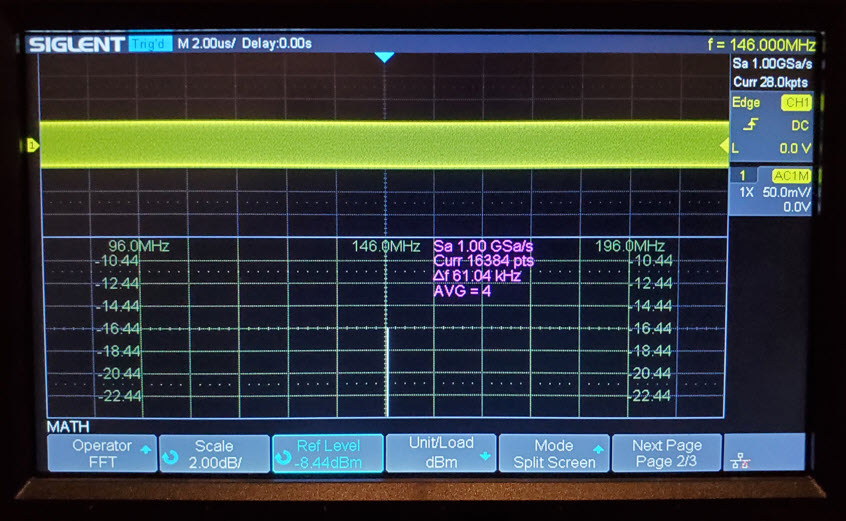

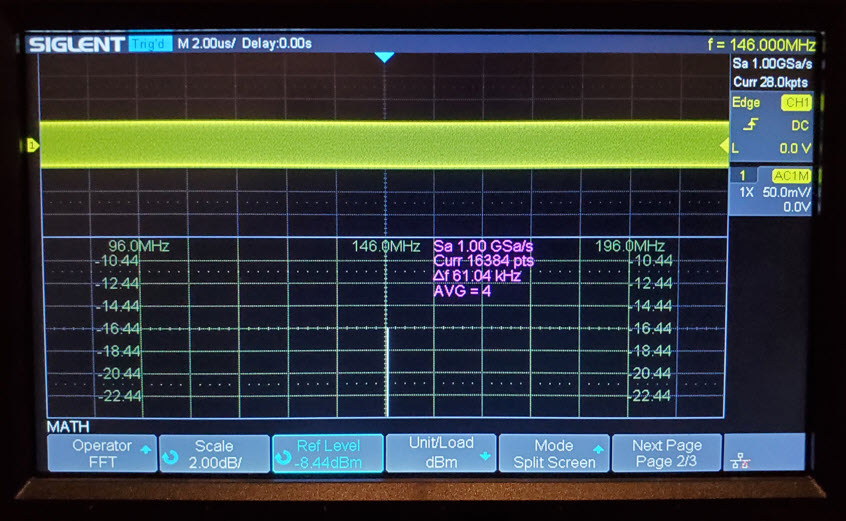

To zero-in on the oscilloscope’s power

measurement at higher precision, I temporarily adjusted the vertical

scale and

allowed the reference level to float. The downside was that the noise

floor could no longer be seen, as noise power fell below the zoomed

display range. On the other hand, the more precise numeric value for

signal power -16.44 dBm was close to the one interpolated for readings

in the HF range (photo below). While it may be optimistic to hope that

tinySA’s generated signal power remains the same at all frequencies,

the fact that the oscilloscope measured a more-or-less constant value

from HF to VHF suggests that generated power is approximately constant

across this much used part of the spectrum. The bane of these

measurements is that we don’t know which instrument has the true or

more nearly true dBm value.

The score is two to one in favor of the function

generator’s output reporting true power, -10 dBm, -20 dBm and -30 dBm,

in that both Siglent bench instruments agree, and neither agrees with the

tinySA.

Exercise 4: Setting aside the puzzling difference in

absolute power measure between the oscilloscope and tinySA, and

recalling that the context of the original motivating issue was filter

measurement, this exercise focuses on the measurement of harmonics and

their relative attenuation with respect to a fundamental. For this and

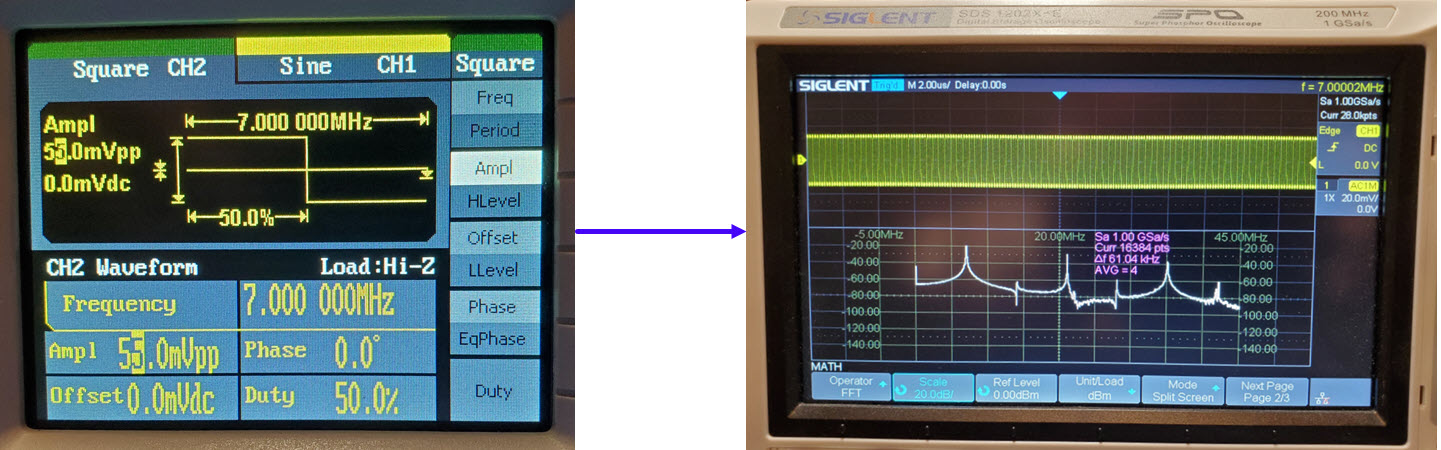

the next two exercises the source signal, i.e., the fundamental, was a

square wave at 7 MHz. I adjusted the function generator’s output to

produce a -20 dBm measure at the oscilloscope. For this measurement the

power scale was temporarily adjusted as before in order to be read with greater precision (not shown). A square wave of 55 mV

P-P sufficed to produce a -20 dBm reading.

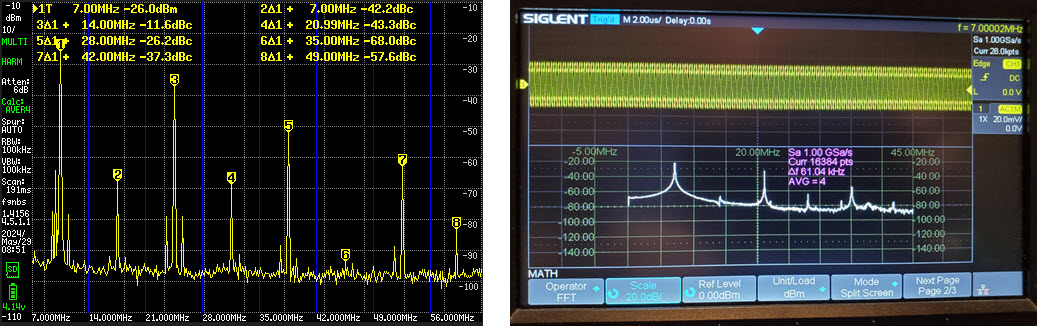

The generated square wave produced

significant harmonics, as expected (above right). The 21 MHz harmonic looks to be at

about the -30 dBm dotted line, while the 35 MHz harmonic is just above

the -40 dBm grid line, roughly -38 dBm. The next part of this exercise

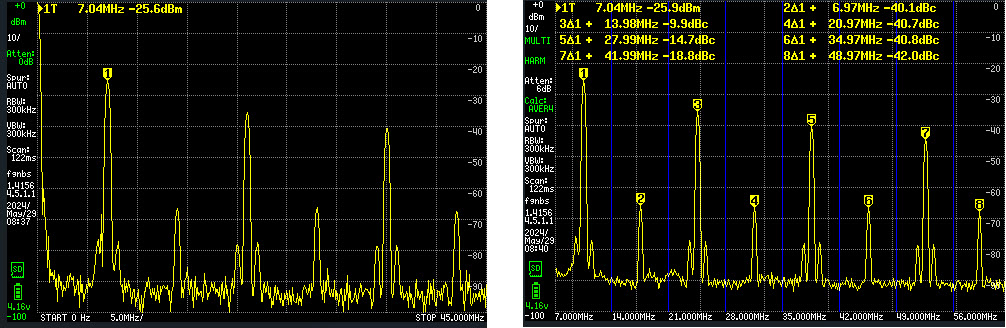

was to observe the same signal on the tinySA Ultra. A neat feature of

the tinySA is its harmonic measurement mode. In this measurement mode,

the unit puts markers on each harmonic peak and displays numeric power

deltas. One other difference is that after the fundamental frequency

and measurement span have been specified,

tinySA adjusts the display range automatically. Evidently the term ‘span’ in

this context refers

to the span above the fundamental, not to the total display width. The

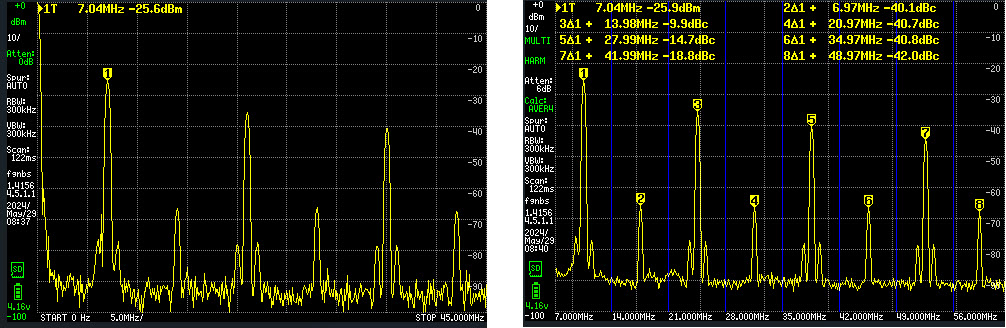

side-by-side image below shows tinySA’s normal spectrum display (left)

and the harmonic measurement display (right).

Note that the fundamental was measured to be -25.6

to -25.9 dBm, or roughly 6 dB weaker than the corresponding

oscilloscope measure, same as in the preceding sine wave exercises.

tinySA’s harmonic measurement display confused me at first. Numeric

frequency numbers are offsets from the fundamental frequency, not

absolute frequencies. Thus marker 3∆1 refers to 7 MHz + 14 MHz = 21

MHz; similarly marker 5∆1 refers to 7 MHz + 28 MHz = 35 MHz. The 21 MHz

(true frequency) harmonic is measured at -9.9 dBc and the 35 MHz

harmonic at -14.7 dBc.4 Textual labels at the bottom of the graph are also confusing. These refer

to the harmonic frequencies not to nearby grid lines. All this is

probably well-understood by experienced users of the TinySA (or other

spectrum analyzers) but was new to me.

If absolute power values are ignored and only

harmonic suppression values considered, the 21 MHz harmonic suppression

is essentially identical to the oscilloscope measure, and the 35 MHz

one about 3 dB stronger (less suppressed) as measured by tinySA.

However, it should be noted that the oscilloscope estimates were made

by eye at a coarse scale (20 dB/scale division).

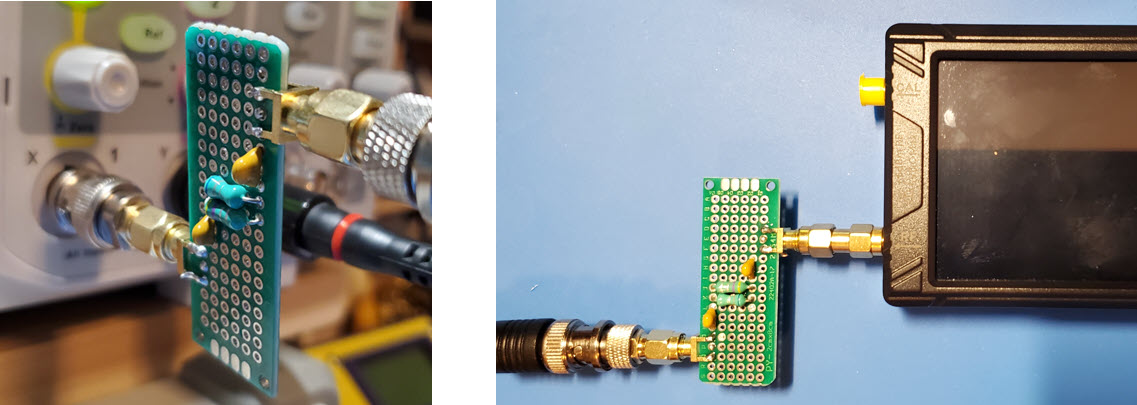

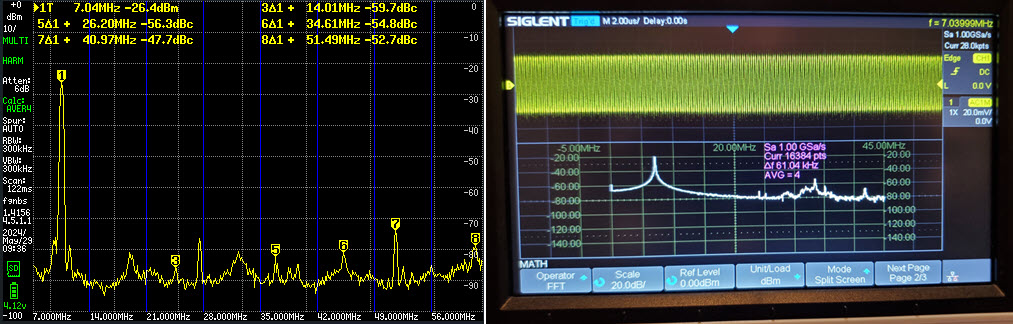

Exercise 5: This exercise and the next one dip into filter

testing. The first test ‘filter’ (not really proven to be a filter at

this point) was a 3-component low pass Chebyshev type, two capacitors

and an

inductor. The filter was connected either to the oscilloscope or tinySA

Ultra using the same coax jumper as in the previous exercise, with a

suitable adapter on the instrument end.

Two questions spring to mind. First does the filter

do anything? That question is most easily assessed by comparing tinySA

harmonic deltas measured with the filter IN to those with the filter

OUT (Exercise 4). The stimulus (source signal) is the same in both

measurement setups, a 7 MHz square wave and -20 dBm or -26 dBm power

level, depending on which instrument you believe. Based on this comparison the

putative low pass filter does seem to do something. Its effect is

most pronounced at 35 MHz and above. The 3∆1 measure (21 MHz true)

decreases by a mere 1.7 dB, while the 5∆1 measure (35 MHz harmonic)

decreases by 11.5 dB, that is from around -40 dBm to -50 dBm.

The second question that can be addressed in this

rather crude filter context is whether the oscilloscope agrees with the

tinySA Ultra, in regard to the relative effect of the filter. Does the

oscilloscope show a similar trend to the one outlined in the previous

paragraph? Although the scale is coarse in the oscilloscope screen

image (right-hand photo above), the 15 MHz harmonic power decrease is

in approximate agreement with the same from tinySA. At 15 MHz the

oscilloscope trace peak falls just below the -30 dBm dotted line (or

roughly 11 dB below the fundamental). The 35 MHz oscilloscope peak

falls just above the -60 dBm grid line, not quite 40 dB below the

fundamental. Without the filter, the oscilloscope had indicated just

above the -40 dBm grid line for this harmonic (first photo in Exercise

4). The change from filter OUT to filter IN is roughly -20 dB. In

summary, the general form of the filter effect is the same for

both instruments, but both absolute power measures and deltas differ to

an extent.

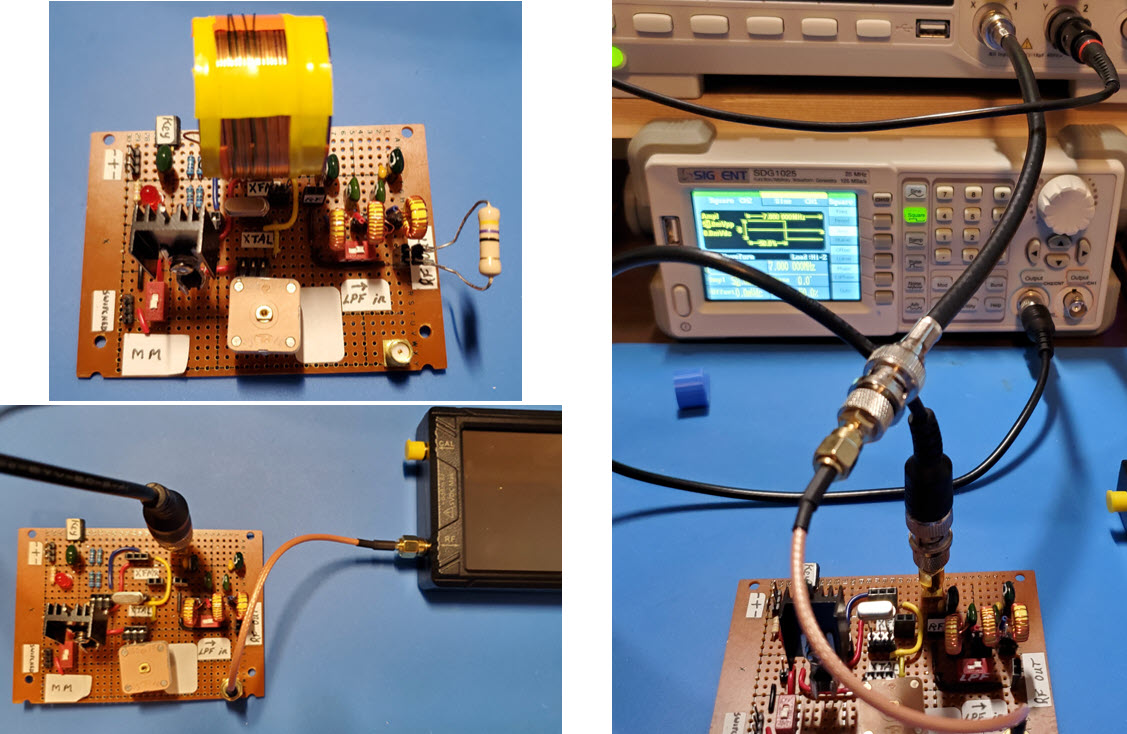

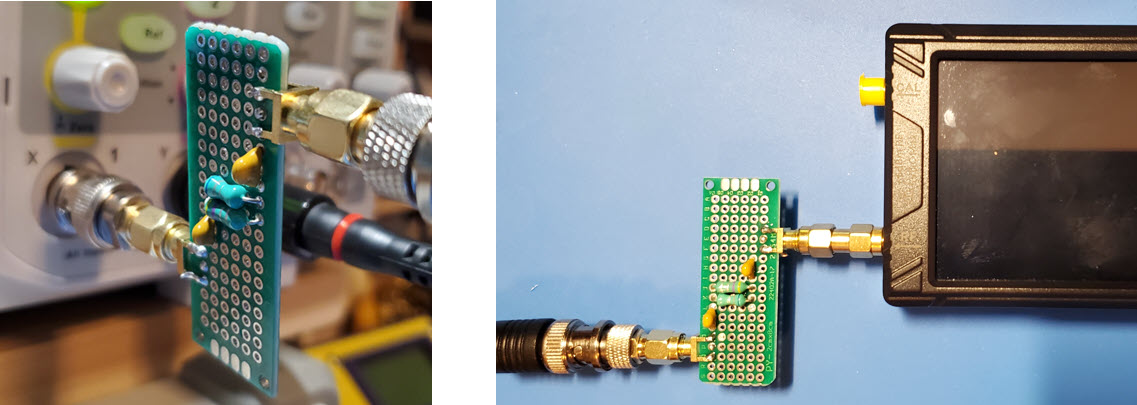

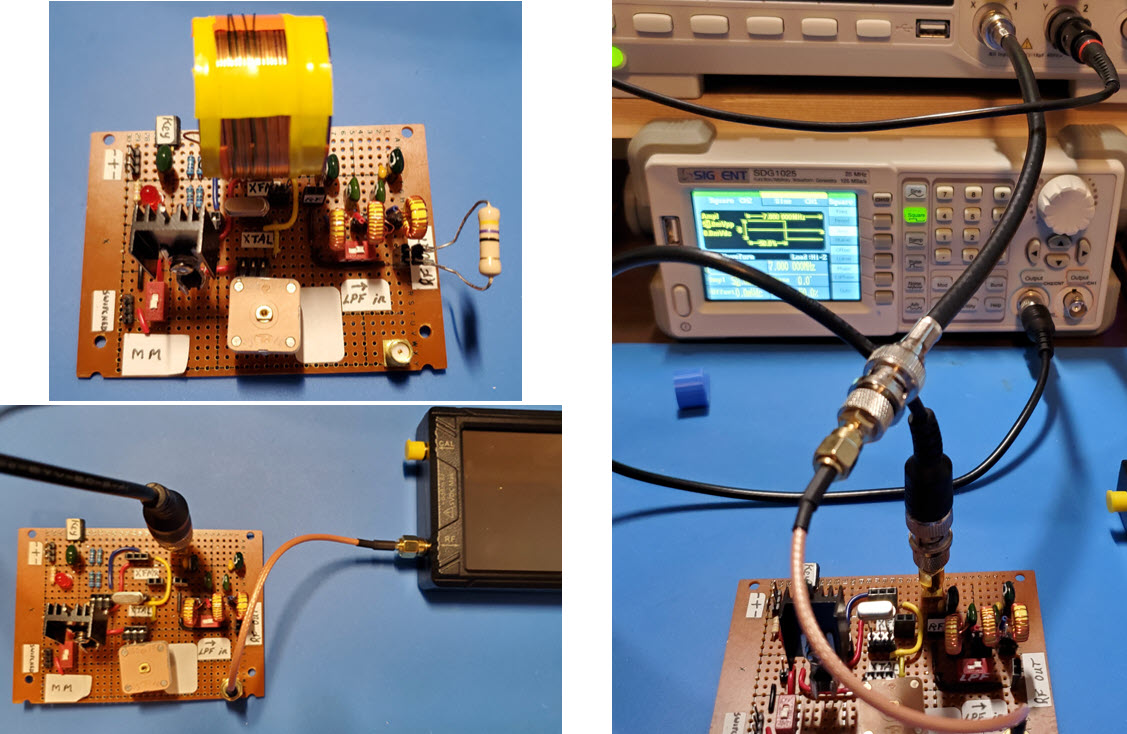

Exercise 6: I recalled having made a 3-stage low pass

filter for 7 MHz, and thought that it had been constructed as a

separate

plugin unit—in fact I was sure it had. However, I have not been able to

locate that construction. Instead I found a Michigan Mighty Mite transmitter with the same

3-stage filter installed (top left photo). Luckily the output

transformer (big

coil at top) could be unplugged, in effect disconnecting the

transmitter from the filter stage. I added a couple of SMA jacks to the

perf board for convenience, and configured filter input and filter output connections

as shown in the photos above. The

upper left photo shows the transmitter before pulling off the output

transformer and dummy load. Of course, the

transmitter was not powered-on during any part of this exercise. The

right hand photo shows the function

generator connected to the filter near the top of the perforated board,

with the filter’s output going to the oscilloscope via an RG-316

jumper, plus an SMA-to-BNC adapter and short piece of 50 ohm coax. The

lower left photo

shows the analogous connection to the tinySA Ultra.

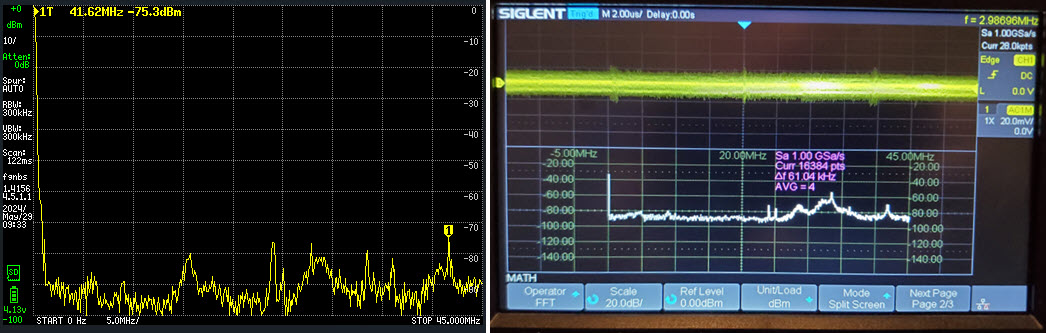

The first thing observed with this filter was a

noticeable increase in noise that appears in both oscilloscope and

tinySA measurements. The illustration above shows representative

tinySA and oscilloscope screens with the filter attached but no

stimulus. It can be guessed that the mess of wires and components on

the Mighty Mite

board were acting as an antenna.

The effect of inserting this particular low pass

filter in the signal path is clear at a glance. Both the tinySA Ultra

and oscilloscope displays show that power is preserved at the

fundamental frequency (essentially unchanged from its measurement with

no filter),

while all the observed harmonics are significantly suppressed. There is

no need to examine the numbers, but deltas range from approximately -50

to -60 dBc, thus confirming the conclusion of casual inspection. It was

reassuring finally to obtain one clearcut result from these somewhat tedious filter

measurements.

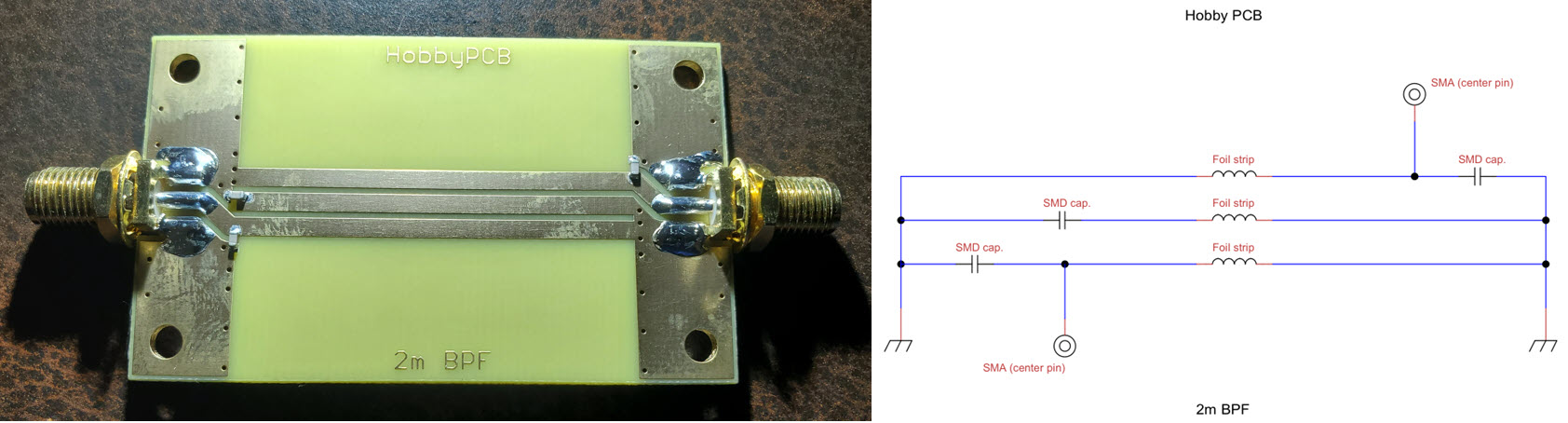

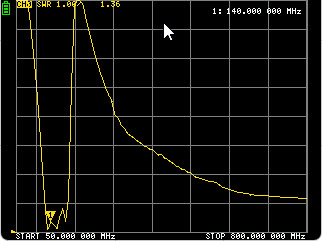

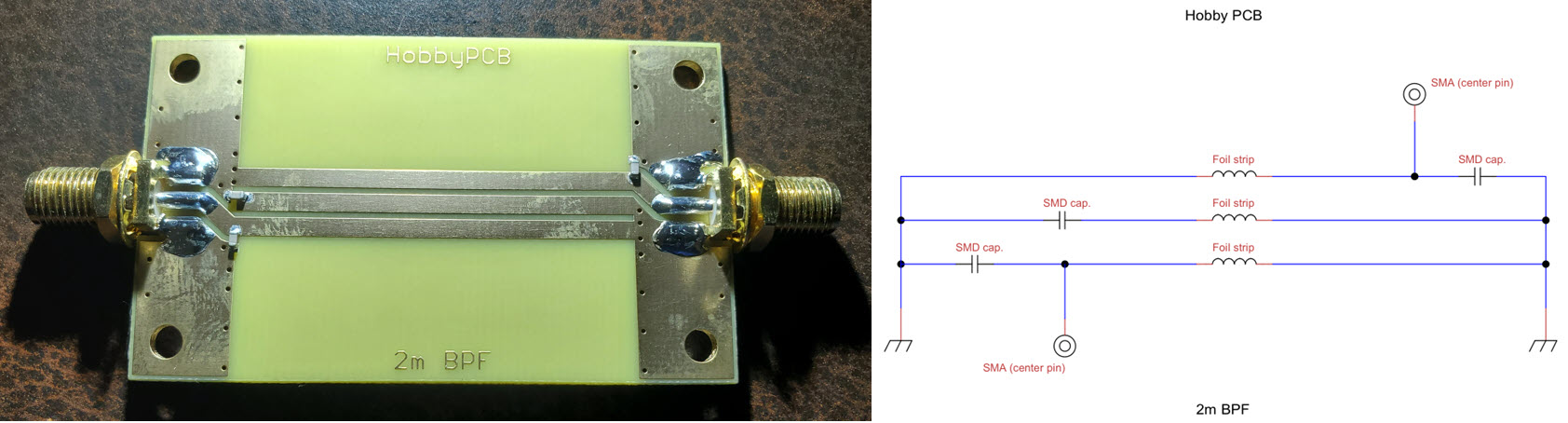

Exercise 7: This exercise explored parameters of a

store-bought 144 MHz band pass filter, this one. The circuit diagram reproduced above is

unofficial

and may be inaccurate. It is my attempt to trace the circuit shown in

the photo.5 Based on the length and width of the foil

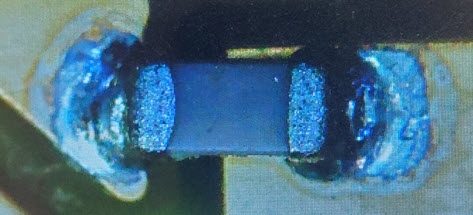

tracks, as measured with a millimeter rule, an on-line calculator yields the value 32 nH for each

of the inductors. Components labeled ‘SMD cap.’ on the diagram were not

marked, and could not be measured in the circuit—See enlarged view at

right. (I was not

inclined to desolder them for measurement.)

Exercise 7: This exercise explored parameters of a

store-bought 144 MHz band pass filter, this one. The circuit diagram reproduced above is

unofficial

and may be inaccurate. It is my attempt to trace the circuit shown in

the photo.5 Based on the length and width of the foil

tracks, as measured with a millimeter rule, an on-line calculator yields the value 32 nH for each

of the inductors. Components labeled ‘SMD cap.’ on the diagram were not

marked, and could not be measured in the circuit—See enlarged view at

right. (I was not

inclined to desolder them for measurement.)

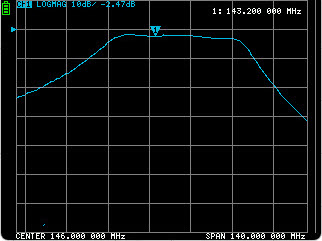

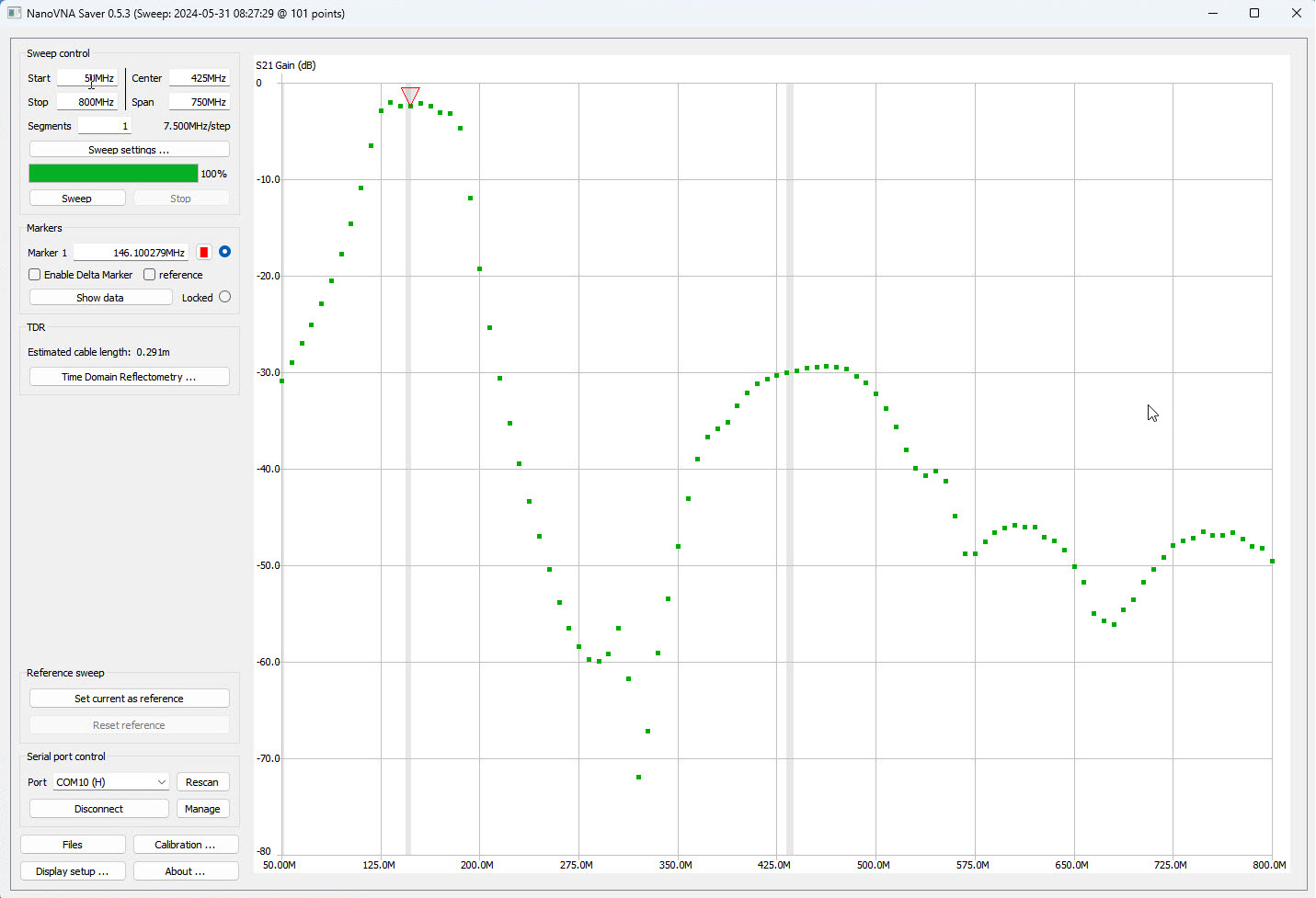

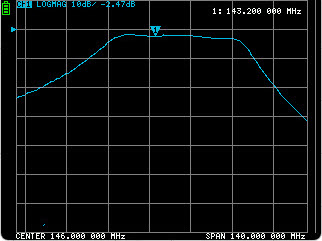

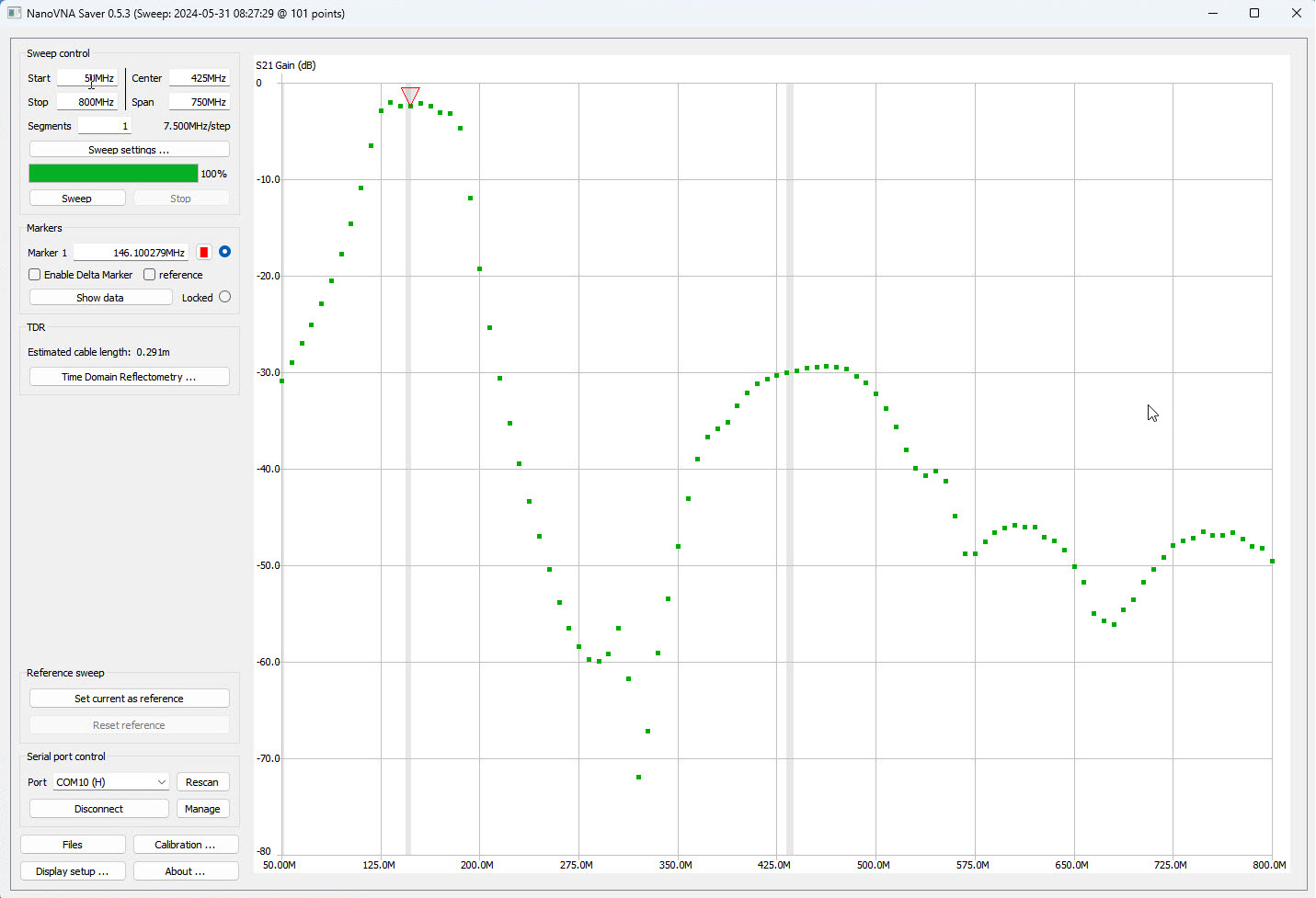

I first examined this filter using the NanoVNA and

subsequently tried a few things with a broad-spectrum RF noise source

and tinySA Ultra. For the NanoVNA observations, the filter was

connected between S11 and S21. Various frequency ranges were tried.

Testing a narrow frequency span resulted in a nearly flat line. I

wanted to see a bump, but this particular filter has a broad pass band.

The screenshot (left) reflects one of many frequency

ranges tested. The display does not include labels for the vertical

scale. However, the NanoVNASaver computer application does indicate

ordinate values. Several measurements were made using the computer

application

as well. Those graphs will be omitted from this summary, partly

in the interest of space, but also because none of them resembled the

specification graphs on the HobbyPCB web page. Those graphs reflected an enormous frequency range (50 to 900

MHz)—I should have noticed!

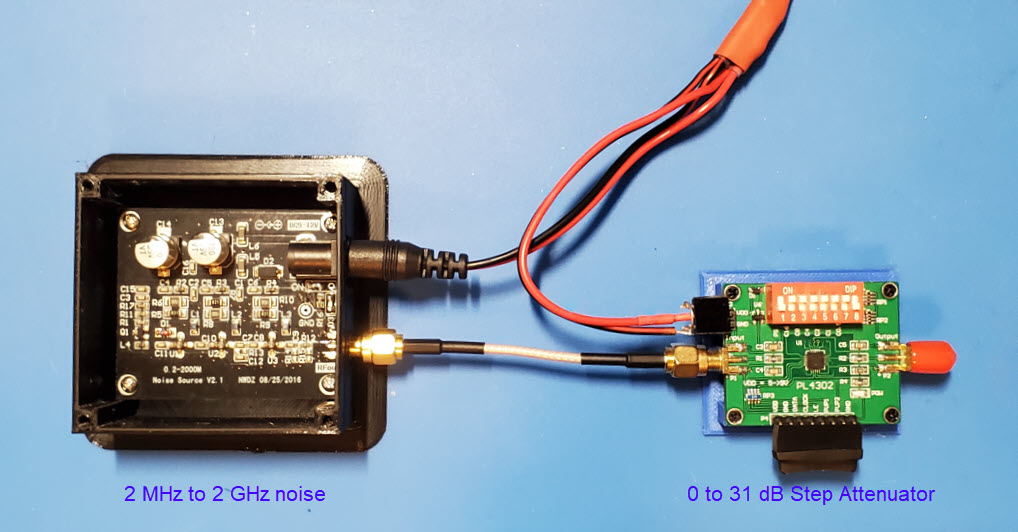

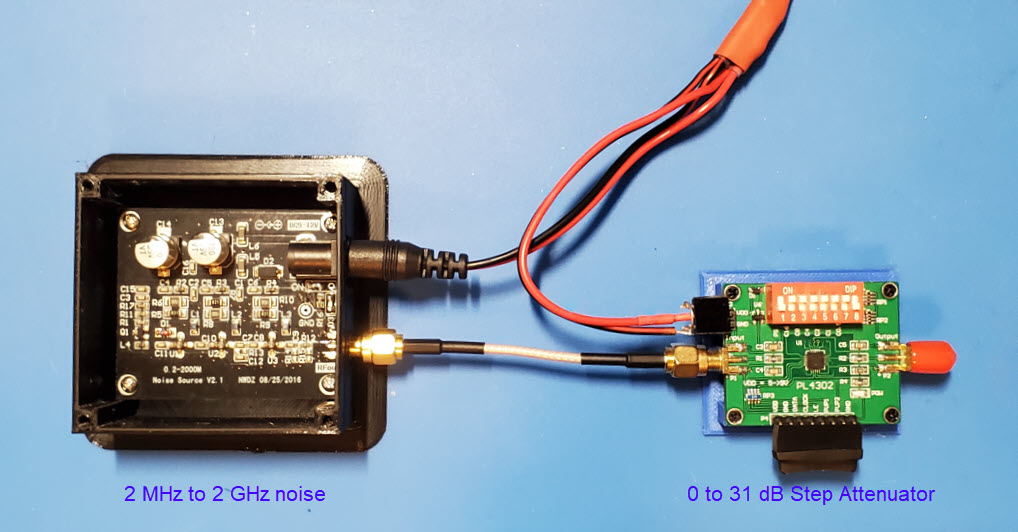

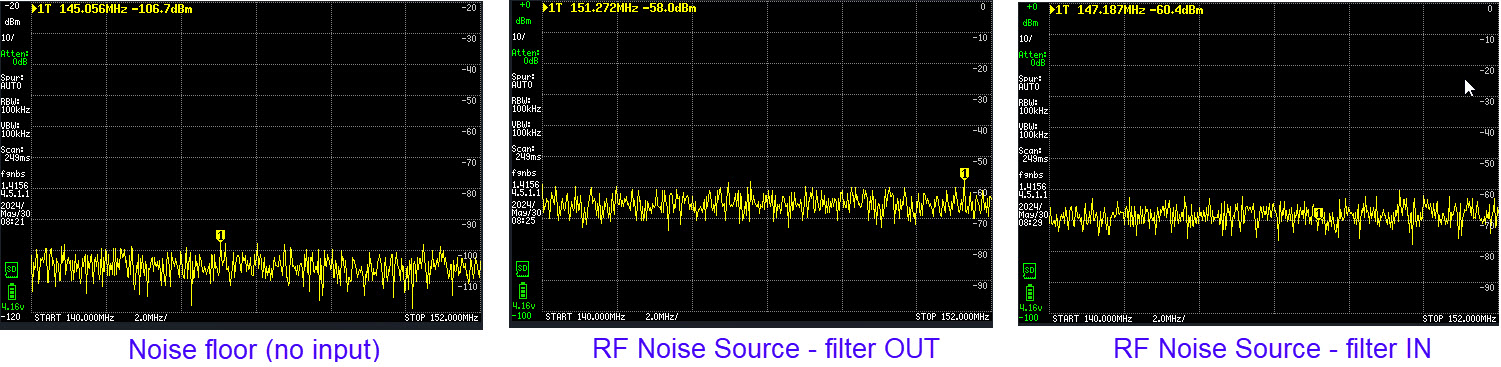

The stimulus configuration illustrated above

consists of a

broad-spectrum RF noise source, 2 MHz to 2 GHz, followed by a step

attenuator. In the photo the attenuator’s DIP switches are set to -31

dB. However, attenuation was subsequently changed to

-16 dB for this exercise, producing between -70 dBm and -60 dBm of

noise power. The attenuator’s output (rightmost SMA connector with red

cover) was connected to the 144 MHz bandpass filter using a double male

SMA adapter. In turn the filter’s output was connected to the tinySA

Ultra’s RF

↔ jack using another short RG-316 jumper. For background levels, the

filter was omitted and the step attenuator was connected directly to the

spectrum analyzer.

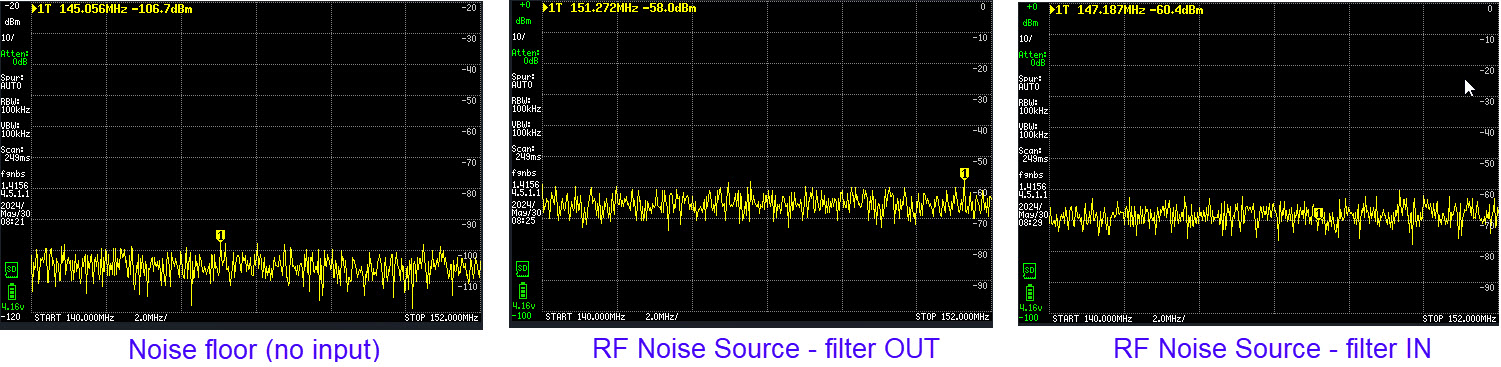

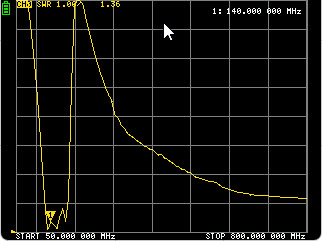

With no input at all (tinySA input not connected)

the noise floor was between -100 dBm and -110 dBm. Not surprisingly,

given the NanoVNA measurements and the published filter specification,

the noise remained flat across the tested frequency span with the band

pass filter in the chain. The level is slightly diminished with the

filter in, a few dB below the middle graph’s measurement. Not much can

be said about these noise measurements. Likely, the observed frequency

span is

too narrow. However, the original idea of these exercises was to

compare TinySA measurements with an oscilloscope’s math mode, so why

not!

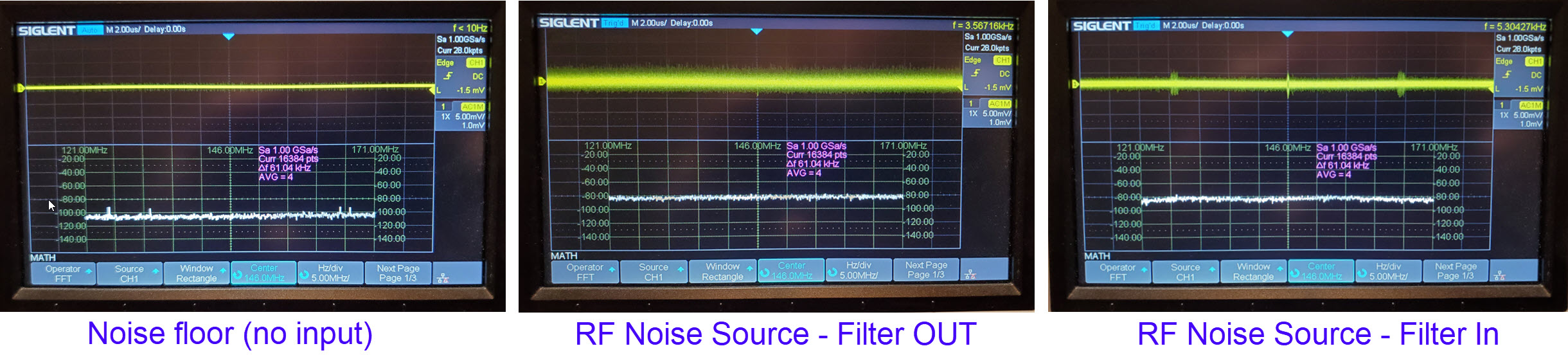

Interestingly, absolute power levels are in

agreement between the oscilloscope and TinySA Ultra in this frequency

range. The oscilloscope’s vertical scale is more compressed than

tinySA’s. However, power is approximately the same, within display

resolution. The oscilloscope’s frequency span (50

MHz) is larger than in the tinySA screenshots.

A great many more observations were made than

were

recorded in screenshots or photos, and unfortunately direct comparisons

are not possible for each test condition. Before starting this exercise

I had expected to see a hole or a bump in the noise due to the filter.

No such effects were observed in any of the tests conducted, but stay

tuned!

Exercise 8: This exercise may be considered a ‘last gasp’

144 MHz filter study, having no relevance to the oscilloscope FFT

question. After reexamining the band pass filter’s specification graphs,

with particular attention to the abscissas, I thought it should be

possible to reproduce a spectrum display having the same shape by

suitable scaling and signal averaging. That turned out to be the case.

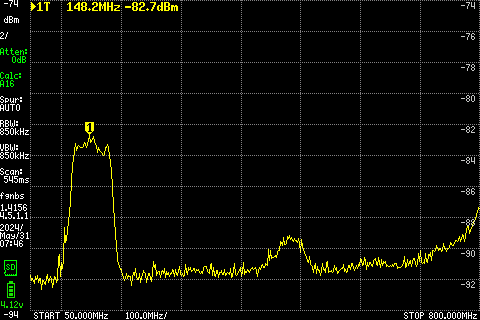

The TinySA Ultra screenshot above reflects a running

average of 16 sweeps through the 144 MHz filter. The RF noise source

was the same as in exercise 7, with the same attenuation settings, etc.

However the sweep spans 50 to 800 MHz and

the vertical (power) scale has been adjusted to 2 dBm/div with

auto-leveling. The larger of the two bumps is centered near the top of

the 2 meter ham band (marker 1). The smaller bump is around 3×

the pass band frequency.

Emboldened by success, if the preceding can be

regarded as such, I decided to have another go with the NanoVNA using

the same broad frequency range for the stimulus. The 144 MHz band pass

filter was connected between S11 and S21 as before.

OK the above graph is big! —Forget any concern for conserving space. As with the preceding

spectrum analyzer noise graph, the above reflects an average of 16

sweeps. In this case averaging makes no difference as the same points

are recorded on each sweep. I chose the ‘Gain’ format because the shape

was indistinguishable from the S21 log MAG plot. However, NanoVNASaver

plots both S11 and S21 log MAG graphs together and they overlap near

the interesting part. It was clearer to plot just S21 Gain. By the way,

the grey bands (vertical strips) in NanoVNASaver graphs represent ham

radio bands.

One of the NanoVNA screenshots resembled

the bottom product specification graph on the HobbyPCB page.

The part at marker 1 is

virtually identical in the comparison graph, while the right part of

the trace to 800 MHz was flat in the specification. However, I do not

know about

the measurement conditions or scale of the latter, which no doubt were

different. Throughout this exercise I have looked for similarities of

shape,

deliberately neglecting the meaning of measurements. In a sense the

objective was to prove that the 144 MHz band

pass filter was in fact a filter. The absence of a salient change

in noise power, as observed in the preceding exercise had led me to

wish for more demonstrable evidence. Similarities in form between the

graphs of this final exercise and the filter specifications would seem

to constitute persuasive evidence for

the supposition in question.

Endnotes

1. AKA math mode. FFT stands for Fast Fourier

Transform, a mathematical procedure for converting a time domain

function to

the frequency domain.

2. Power is RMS voltage squared divided by impedance.

63 mV P-P divided by 2*√2 = 22.27 mV RMS (or 0.02227 volts). 0.02227

volts squared divided by 50 ohms is .0000099225 watts (.0099225 mW).

[An easy-to-remember formula for RMS power in watts as a

function of peak to peak voltage is P = E2p-p

/ 8Z. The result is the same, of course, because (2√2)2 =

8.] Converting .0099225 mW to dBm,

10 times Log(.0099225) is -20.03, close enough. By

similar calculation, 200 mV corresponds to -10 dBm, and 20 mV to -30

dBm.

3. Oscilloscope: AC coupled, 50 ohms. FFT:

1 GSa/sec, 45 MHz swath of specturm, 214 bins. Display: 0

dBm reference, 20 dB per solid grid line, unless otherwise noted.

4. dBc stands for ‘decibels relative to carrier’.

5. The reverse side of the PCB (not pictured) has a foil covering to which the SMA jacks are soldered, making a common ground.

Project descriptions

on this page are intended for entertainment only.

The author makes no claim as to the accuracy or completeness of the

information presented. In no event will the author be liable for any

damages, lost effort, inability to carry out a similar project, or

to reproduce a claimed result, or anything else relating to a decision

to use the information on this page.

Exercise 7: This exercise explored parameters of a

store-bought 144 MHz band pass filter, this one. The circuit diagram reproduced above is

unofficial

and may be inaccurate. It is my attempt to trace the circuit shown in

the photo.5 Based on the length and width of the foil

tracks, as measured with a millimeter rule, an on-line calculator yields the value 32 nH for each

of the inductors. Components labeled ‘SMD cap.’ on the diagram were not

marked, and could not be measured in the circuit—See enlarged view at

right. (I was not

inclined to desolder them for measurement.)

Exercise 7: This exercise explored parameters of a

store-bought 144 MHz band pass filter, this one. The circuit diagram reproduced above is

unofficial

and may be inaccurate. It is my attempt to trace the circuit shown in

the photo.5 Based on the length and width of the foil

tracks, as measured with a millimeter rule, an on-line calculator yields the value 32 nH for each

of the inductors. Components labeled ‘SMD cap.’ on the diagram were not

marked, and could not be measured in the circuit—See enlarged view at

right. (I was not

inclined to desolder them for measurement.)