Billions

and Billions

Remembrance of

things past: Most people of my generation recall Carl Sagan’s

‘billions and billions’, pronounced with an

exaggerated hard ‘b’ sound, except that Carl Sagan didn’t actually

utter those words.1 The true source of this

memory was Johnny Carson spoofing Carl Sagan! Be that as it may, there

are billions of stars in our galaxy and billions of galaxies in the

universe, just as Carl Sagan said there are. Perhaps a lesser known

fact is that our amateur radio transmitters spew forth billions and

billions of photons per second. Indeed the word ‘billions’ is much too

small to express the numerosity of the energy packets that we routinely

cast into our world and beyond.

It is not necessary to have studied physics to know

that x-rays are more energetic than visible light—that’s why the dental

technician covers us with a heavy blanket before hastening from the

room to shoot the required annual image of our so-called ‘bite’.

Similarly we know that visible light is more energetic than microwaves,

which are more energetic than VHF/UHF, and so forth through high

frequencies, medium and long waves, all the way down to the Schumann

resonances.2 Come to think of it, a person

does not need to have studied physics in order to learn almost anything

about our universe nowadays. The answer can be found in Google 101 or

StartPage or DuckDuckGo or wherever you like.

Physics, or science in general, often deals with

numbers and I’ve learned over the years that many people are

uncomfortable with numbers. They are okay with reading the word

‘billion’ but the number 1,000,000,000 (which is the same thing) makes

them cringe. A sort of workaround for this problem is an extended set

of words for bigger and bigger quantities, trillion, quadrillion,

quintillion, and so forth. The same works in the other direction,

micro, nano, pico, femto, etc.3 But there

comes a point where you need numbers, as the words become awkward, like

working with Roman numerals—I’m writing this paragraph in MMXXIII.

Maybe the solution is to promise something. “If you

can tolerate a few numbers, I will tell you how many photons a 100 Watt

transmitter shoots forth per second at 7.150 MHz.” But wait, there is

no

need to suffer. With the admittedly unrealistic assumption

that the entire 100 Watts power is effectively radiated at the

specified frequency, I will state the answer to an absurd degree of

precision. It is

twenty-one octillion, one hundred seven septillion, five hundred

fifty-four sextillion, nine hundred sixty quintillion, thirty

quadrillion, ninety-five trillion, six hundred ninety billion, more or

less. How satisfying was that? —Not very!

Biting the numbers

bullet: We are ham radio operators, after all. We must deal with

some numbers, like how long to

cut the dipole wires, or how much reflected power our transmitter is

able to tolerate—oops! We must also have

passed a license exam, though that may have been in the distant past,

and it’s possible we could have forgotten some of those answers. Well,

surely we have not forgotten such fundamentals as the fact that

wavelength is inversely proportional to frequency. Though it may seem

less intuitive, it is just as simple to work out the immense number of

photons per second at 7.150 MHz, as it is to convert

frequency to wavelength, or vice versa. Instead of the speed of light,

a different constant of nature enters the picture. This one describes

how the energy of a photon varies with its frequency.

Planck’s constant is an exceedingly small

number. In ordinary decimal notation it is

0.000000000000000000000000000000000662607015 Joule-seconds. Scientists

and engineers use a more compact notation, 6.626 × 10-34

J-s, but never mind that just yet.

The

energy of a photon is Planck’s

constant multiplied by its frequency in Hertz. You can see where

multiplying this miniscule number by a few billion isn’t

going to tip the scale very far! Now, one last piece of arithmetic

lore...

Dividing by a small number makes a large number. For example, dividing

by one-half is the same as multiplying by two. Dividing by one-tenth is

the same as multiplying by 10, and so forth. More to the point,

dividing power in Watts by the energy of a photon (at a given

frequency) gives the number of photons per second being generated. With

this one additional fact you can check my arithmetic on the 7.150 MHz

problem. —I have been known to be wrong.

Penetrating the mist:

It is one thing to calculate how many photons are generated, but how

many of them are getting through to Timbuctoo?—either

the

one in Mali, or the one in California. Stay tuned.

* * *

When the operator says you are 5-9 in Timbuctoo, it is best not to take

the report too literally. Surely every station cannot be 5-9 in

Timbuctoo! Alas, politeness has overtaken accuracy in the signal

reports business. Your true signal is more likely to be the one

illustrated pictorially on the left. For the sake of this exercise,

let’s assume that the transmitted signal is received as S3 in

Timbuctoo, and that the S-meter has been calibrated. The latter would

rarely be a safe assumption, but we have to start somewhere. According

to hamwaves.com,

a reading of S3 equates to -109 dBm at 50 ohms,

provided

that the S-meter is ‘well-designed’ and has been

calibrated for the high frequencies.4 But,

what does that mean?

When the operator says you are 5-9 in Timbuctoo, it is best not to take

the report too literally. Surely every station cannot be 5-9 in

Timbuctoo! Alas, politeness has overtaken accuracy in the signal

reports business. Your true signal is more likely to be the one

illustrated pictorially on the left. For the sake of this exercise,

let’s assume that the transmitted signal is received as S3 in

Timbuctoo, and that the S-meter has been calibrated. The latter would

rarely be a safe assumption, but we have to start somewhere. According

to hamwaves.com,

a reading of S3 equates to -109 dBm at 50 ohms,

provided

that the S-meter is ‘well-designed’ and has been

calibrated for the high frequencies.4 But,

what does that mean?

dBm to Watts:

First, observe that the letter ‘m’ in dBm stands for ‘milliwatt’.

That’s easy enough. However, at this point it becomes necessary to

introduce a swear word. If you already hang out with swear words, then

this one is not particularly fearsome. It is the word ‘logarithm’. More

precisely it is the common logarithm, where ‘common’ refers to base-10,

the number base that is commonly

used for counting things. The symbol dB (decibels) is nothing more than

ten times the base-10 logarithm of a number. One of the shortcuts we

learn in ham radio is that a 3dB power gain corresponds to doubling the

power. Doubling, of course, is the same as multiplying by 2, and the

base-10 logarithm of 2 is approximately 0.3, which multiplied by 10

makes 3 dB.

Before losing track let’s return to the S-meter

reading. Our signal was S3, or -109 dBm in Timbuctoo. Although these

intermediate steps are probably explanation overkill, to be clear, -109

dB means

that the logarithm of the power ratio is -10.9 (divide dB by 10). To

work backwards from dBm to power, multiply 1 milliwatt (.001 Watts) by

10-10.9. As may be expected, the result is a very

small quantity. Expressed to an absurd number of

decimal places the value works out to be

.0000000000000125892541179416721... Watts. Believe it or not, there is

a prefix for this miniscule amount of power. Rounded to 3 places, it is

12.6 femtowatts.

The number of photons per second impinging upon the

receiver is this small number divided by the previously computed energy

of a photon at 7.15 MHz (Planck's constant multiplied by 7,150,000 Hz).

Drum roll... The number is 2,657,283,732,002 (more or less). In words,

it is two trillion, six hundred fifty-seven billion, two hundred

eighty-three million, seven hundred thirty-two thousand and two photons

per second. In contrast to the enormous number that was computed for

the transmit power, this one is small enough to be dollars instead of

photons! As dollars it would be a small fraction of the US national

debt.5

Photons per unit

area per second: Counting energy packets that equate to an

S-meter reading was messy to say the least. However, to continue in the

spirit of glorifying big numbers, and expressing them to preposterous

precision, the exercise can be carried one step

further. The concept is called ‘photon flux’. Stay tuned.

* * *

Here comes another swear word, ‘isotropic’. It is

the ‘i’ in dBi, in case you happen to have seen that symbol. The term

‘isotropic’ means ‘same in every direction’. Ham radio antennas are not isotropic. On the other hand,

the gain of a directional antenna may be conveniently expressed in dBi

units, or decibels over isotropic. For example, the gain of a dipole

(in free space) is 2.15 dBi. The dipole itself often serves as a comparison

reference for expressing the gain of other antenna types. Decibels

(logarithms)

are additive, so if a Yagi antenna has 8 dB forward gain with respect

to a dipole, it would be the same to say its forward gain is

approximately 10

dBi. Bear in mind that real antennas are not ideal antennas. Real

antennas are affected by their height above ground, and countless other

installation-specific environmental factors.

The word isotropic

plays an important role in a concept called the ‘inverse square law’. I

don’t want to make more of this than is obvious. If a substance

emanates outwards from a point equally in all directions, then at any

given distance the substance will be dispersed evenly on the surface of

an imaginary sphere whose radius is said distance. In school

we either deduced or memorized (and then quickly forgot) the formula

for the surface area of a sphere 4πr2, where r stands for its radius. In the

inverse square law, the letter d

(distance) replaces r

(radius) in this expression.

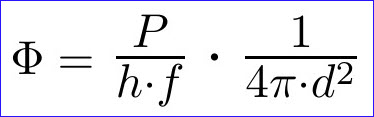

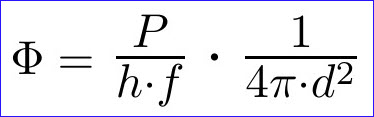

Putting the inverse square law together with the count of photons at

the source leads to the concept of photon flux,

sometimes denoted by an uppercase Φ.

Flux is simply the number of photons per second per unit area at a given distance

from the source.

At this point it may be necessary to

apologize for sneaking in a potentially frightening formula. But

each of

the symbols in the formula stands for something that has been explained

already, P for power in

Watts, h for Planck’s

constant, f for frequency in

Hz, and d for distance in

whatever units you want. If distance is specified in meters, then area

will be meters squared, and so forth. As illustrated here, the photon

flux calculation assumes isotropy. For convenience the formula has been

split into sub-expressions to emphasize the radiative source (left) and

its inverse square diminution (right).6

At this point it may be necessary to

apologize for sneaking in a potentially frightening formula. But

each of

the symbols in the formula stands for something that has been explained

already, P for power in

Watts, h for Planck’s

constant, f for frequency in

Hz, and d for distance in

whatever units you want. If distance is specified in meters, then area

will be meters squared, and so forth. As illustrated here, the photon

flux calculation assumes isotropy. For convenience the formula has been

split into sub-expressions to emphasize the radiative source (left) and

its inverse square diminution (right).6

Effective area:

Ham radio transmit antennas are not isotropic. And receive antennas

don’t resemble a chunk from a spherical collecting surface. Moreover,

who’s going to climb an antenna tower with a tape measure in hand, and

what

would they

do with it if they did? As it happens, nobody has to climb the tower,

or measure antenna parts because, according to this page, “the effective

area of an antenna ... is the area of the idealized antenna that

absorbs as much net power from the incoming wave as the actual antenna

[does].” With a few lines of symbol manipulation that same page deduces

the effective area of a (Hertzian) dipole7

to be three times the wavelength squared divided by 8π.

In the spirit of fudging when expedient to do so, I will use this

expression to compute the area of the make-believe receive antenna in

Timbuctoo.

The frequency 7.150 MHz falls in the 40 meter ham radio

band. At this frequency the free-space

wavelength is closer to 41.9

meters, but no-matter. Let’s say λ ≈ 40 meters. That should be close

enough. Applying the effective area formula from the preceding

paragraph we get approximately 190 m² for the area of the receive

antenna. (Check me!) At this point it is time to let go the excessive

precision of photon counts. Dividing 2,657 billion by 190 meters

squared obtains a flux of approximately 14 billion photons per second

per meter squared at the receiving antenna. Hmm. Now I’m thinking of

even crazier calculations, like given the distance to Timbuctoo, how

would the antenna’s measured

gain compare to the isotropic flux calculation for the same distance.

Of course it would not be necessary to use photon flux in the

calculation, as the same comparison can be done with power in Watts.

Big numbers

on this page are just for fun.

Wrap up and wind

down:

Waves are everywhere, especially in ham radio,

long waves, medium waves, shortwaves, waves of voltage and current on

the transmission line and antenna, electric and magnetic components of

the RF wave, in-phase and quadrature to the SDR, and so on.

Wrap up and wind

down:

Waves are everywhere, especially in ham radio,

long waves, medium waves, shortwaves, waves of voltage and current on

the transmission line and antenna, electric and magnetic components of

the RF wave, in-phase and quadrature to the SDR, and so on.

Waves correspond to the natural way of thinking

about radio, as we know it. They form a conceptualization that works,

and has passed the test of time. Nevertheless it is fun to contemplate

the magic of radio in a different way, to visualize billions and

billions of infinitesimal beadies shooting forth, bouncing and

penetrating and otherwise wending their way to remote and exotic places.

1. Chapter 1 in Sagan’s posthumous Billions & Billions... Sagan did intentionally

pronounce the word with a hard ‘b’ to emphasize that he was not saying

‘millions’.

2. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Schumann_resonances

3. https://www.varsitytutors.com/hotmath/hotmath_help/topics/big-and-small-numbers

4. S-meter calibration differs for VHF/UHF. For

example, S9 at HF translates to -73 dBm at 50 ohms, while for VHF/UHF

it is -93 dBm.

5. 8.4% at the time of this writing (https://www.usdebtclock.org/).

6. In the flux formula, frequency is sometimes

expressed as the speed of light divided by wavelength (f = C/λ), which puts wavelength in

the numerator and the constant C in the denominator.

7. Directivity = 3/2.

Project descriptions on this page are intended for entertainment only.

The author makes no claim as to the accuracy or completeness of the

information presented. In no event will the author be liable for any

damages, lost effort, inability to carry out a similar project, or to

reproduce a claimed result, or anything else relating to a decision to

use the information on this page.

When the operator says you are 5-9 in Timbuctoo, it is best not to take

the report too literally. Surely every station cannot be 5-9 in

Timbuctoo! Alas, politeness has overtaken accuracy in the signal

reports business. Your true signal is more likely to be the one

illustrated pictorially on the left. For the sake of this exercise,

let’s assume that the transmitted signal is received as S3 in

Timbuctoo, and that the S-meter has been calibrated. The latter would

rarely be a safe assumption, but we have to start somewhere. According

to hamwaves.com,

a reading of S3 equates to -109 dBm at 50 ohms,

provided

that the S-meter is ‘well-designed’ and has been

calibrated for the high frequencies.4 But,

what does that mean?

When the operator says you are 5-9 in Timbuctoo, it is best not to take

the report too literally. Surely every station cannot be 5-9 in

Timbuctoo! Alas, politeness has overtaken accuracy in the signal

reports business. Your true signal is more likely to be the one

illustrated pictorially on the left. For the sake of this exercise,

let’s assume that the transmitted signal is received as S3 in

Timbuctoo, and that the S-meter has been calibrated. The latter would

rarely be a safe assumption, but we have to start somewhere. According

to hamwaves.com,

a reading of S3 equates to -109 dBm at 50 ohms,

provided

that the S-meter is ‘well-designed’ and has been

calibrated for the high frequencies.4 But,

what does that mean? At this point it may be necessary to

apologize for sneaking in a potentially frightening formula. But

each of

the symbols in the formula stands for something that has been explained

already, P for power in

Watts, h for Planck’s

constant, f for frequency in

Hz, and d for distance in

whatever units you want. If distance is specified in meters, then area

will be meters squared, and so forth. As illustrated here, the photon

flux calculation assumes isotropy. For convenience the formula has been

split into sub-expressions to emphasize the radiative source (left) and

its inverse square diminution (right).6

At this point it may be necessary to

apologize for sneaking in a potentially frightening formula. But

each of

the symbols in the formula stands for something that has been explained

already, P for power in

Watts, h for Planck’s

constant, f for frequency in

Hz, and d for distance in

whatever units you want. If distance is specified in meters, then area

will be meters squared, and so forth. As illustrated here, the photon

flux calculation assumes isotropy. For convenience the formula has been

split into sub-expressions to emphasize the radiative source (left) and

its inverse square diminution (right).6  Wrap up and wind

down:

Waves are everywhere, especially in ham radio,

long waves, medium waves, shortwaves, waves of voltage and current on

the transmission line and antenna, electric and magnetic components of

the RF wave, in-phase and quadrature to the SDR, and so on.

Wrap up and wind

down:

Waves are everywhere, especially in ham radio,

long waves, medium waves, shortwaves, waves of voltage and current on

the transmission line and antenna, electric and magnetic components of

the RF wave, in-phase and quadrature to the SDR, and so on.