House of

Geiger: The 3D-printed enclosure for the Geiger

Counter somewhat resembles a house or barn, hence the whimsical name. I

was not able to visualize how to fit the four sub-boards into a project

box. So I decided to start on an enclosure by constructing a basement

for the Geiger

PCB, the board that includes the Geiger-Müller tube and associated

circuitry. Next I

added

a first floor for the microcontroller board. At this point I

realized it would be possible to secure the first floor to the basement

by making a tube cover (slotted blue piece in photo) to fit over the

top of the ground

floor’s baseboard, i.e., its front edge. A small signal conditioning

circuit board occupies the second floor. That component’s

scaffolding is hidden from view in the photo, and not by

accident. Finally, the display screen (skylight) and input

pushbutton (air vent) attach to a separate panel that is caulked, i.e.,

glued, to

the

roof.

Variants of a popular open source Geiger Counter

board may

be purchased from many sources, either assembled or in kit form. The one used in this project came

assembled for $33.47 plus a few dollars shipping. My only complaint

is that I couldn’t find documentation for the tube. It is

marked J303ß. I did find a datasheet for the J305ß, which is probably

similar. My second only complaint is that the tube was too short for the spacing

of spring clips intended to

hold it. I had to move one of them, and solder a jumper wire from the

repositioned clip to its original

foil pad.

Project

components: The Geiger Counter PCB includes a

small speaker which makes the familiar clicking sound when particles

are

detected. It also has a headphone jack and an on-board pin header to

convey

the pulse signal externally. That is where the fun begins—Just

listening to random

clicks produced by

background radioactivity tends to lose interest after a short time.

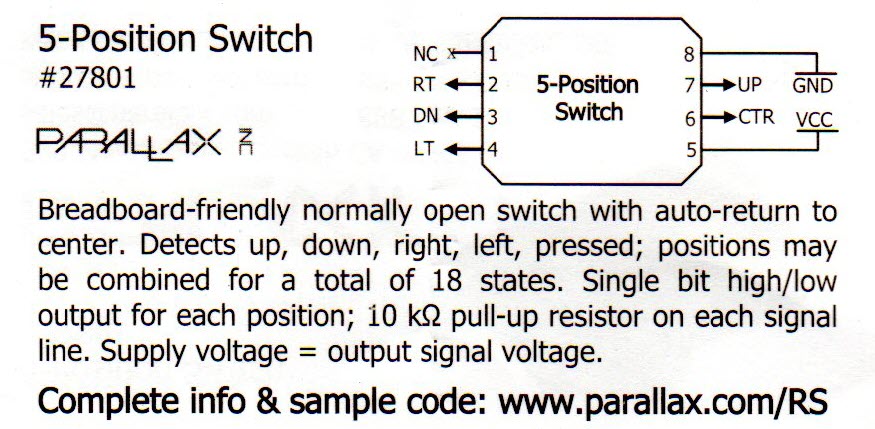

I had a couple of ideas in mind before

starting the project. One was to use a small color OLED as the display

device, and a 5-position pushbutton switch for input. A few years ago,

when

Radio Shack was closing US retail stores, I purchased odds and ends

on-sale, hoping to find interesting uses for them someday. One

such purchase was a switch that looks like a pushbutton but behaves

more like a joystick. It is not a joystick, but a 5-position

switch.

The package insert is reproduced above. My thought was that the

combination of OLED

and multi-position switch could be made to function similarly to a

touchscreen, not the same exactly, but close enough to construct a

numeric calibration

option without the need for a keyboard.

Another preliminary thought was to

include images as part of a ‘quantum coin toss’

option. I will describe this idea further below, but its significance

for the planning stage was that the application would need

memory—bitmaps

consume memory. I started playing with an Arduino Uno and also tested a

Nano,

but encountered trouble on two fronts. One was the bitmaps memory

issue. The other problem is harder to describe. I am not sure that I

understand it completely, but it had to do with the limited interrupt

pin

assignments that are available in these architectures. In any case, the

answer to both problems was to substitute an Arduino Mega 2560. Teensy

would

also

have worked, but the project provided a good excuse to explore a new-to-me

platform.

Microcontroller

interface:

The 1.5 inch color

OLED (this one) supports only SPI

(Serial Peripheral Interface)

connectivity.1

I have wondered why 0.96

inch monochrome OLEDs include i2c support

(Inter-Integrated Circuit serial bus, pronounced

‘i-squared c’), while the

slightly larger color ones are SPI only, at least

those I have found to purchase. In the original Uno-based

exploration, DIO pins 4 - 8 were assigned to SPI, reserving pin 2 for

interrupt input. After changing

to the Mega platform and a different interrupt pin, I left the SPI

assignments as they were.

The Geiger Counter’s output

pulse was a bit messy and also variable. To condition it for input to

the microcontroller I ran it through an inverting Schmitt trigger to a

one-shot (diagram above). Output from the one-shot goes to one of the

Mega’s additional interrupt-capable pins (#18). Consecutively numbered pins 22 - 27 were

assigned to the 5-position switch, in order to make use of a

space-saving double-row

header for the physical connection. SPI and pushbutton pin

assignments are more-or-less arbitrary. However,

pin numbering in the sketch (software) must

correspond to the scheme actually used for connecting devices (or

vice-versa)—this aspect of numbering is not

arbitrary.

Heads

or

tails: It is possible to purchase an attractively

packaged pre-made Geiger Counter, for example this one,

for not much more than the cost of

this

project’s

parts. The main

reason to build or assemble a Geiger Counter is to personalize the

design, in other words to express whatever crazy ideas

come to mind. One such idea was to include a graphical coin toss

option. This idea was partly inspired by the resource described on this page,

which dates from 1996 (impressive!). I had played with the ‘physical

random numbers’ idea previously, but in a project that used electronic

white noise as the source of randomness (write-up here).

Heads

or

tails: It is possible to purchase an attractively

packaged pre-made Geiger Counter, for example this one,

for not much more than the cost of

this

project’s

parts. The main

reason to build or assemble a Geiger Counter is to personalize the

design, in other words to express whatever crazy ideas

come to mind. One such idea was to include a graphical coin toss

option. This idea was partly inspired by the resource described on this page,

which dates from 1996 (impressive!). I had played with the ‘physical

random numbers’ idea previously, but in a project that used electronic

white noise as the source of randomness (write-up here).

Pressing the pushbutton in the ‘down’ direction at the home screen

causes either heads or tails to display for one second, momentarily

replacing the radiation warning graphic that normally decorates that part of the display. By the way,

the radiation image caused some OLED burn-in that can be seen in the

photo

(left) as bright spots on the coin image. It would surely be better

to display multiple bitmaps (or variant forms with contrasting colors)

instead of one constant image, to reduce or prevent burn-in.

The coin toss works as follows. In the Arduino Mega

platform the smallest grained timing function has a resolution

of 4

microseconds. To be precise, the built-in micros() function always

returns a multiple of 4 microseconds. Thus, elapsed time in

microseconds (modulo 8) can be mapped to

parity.2

Since the timing of ‘clicks’ (atomic decay events)

reflects nature’s randomness, I refer to this option as a ‘quantum coin

toss’. Now a curious observation... We humans are not wired to detect

randomness. On the contrary we tend to expect randomness to produce a

sort of short-term balance. A small number of heads or tails should

even-out, we think. Thus, it is easy to become persuaded that the coin

toss

option does not

behave randomly. To verify the process, or rather to ascertain whether

in fact the coin toss is fair, I left the Geiger Counter powered-on and

detecting background radioactivity around the clock for approximately a

week, yielding 44,720 tosses.3 (No doubt this side-study

contributed to the OLED burn-in problem.) I then ran the NIST

random number statistical assessment tool ‘assess’

on the data, the same suite of tests as was used in

the

aforementioned white-noise ‘physical random number’ project.

This weeklong accumulation of data passed 145 of 147 ‘non-periodic template’

tests and the dozen or so other statistical sub-tests that make up the NIST

suite. The

final ‘Universal Statistical Test’ requires a considerably larger

sample size, which would have been desirable, but based on

completed test results, I conclude that this particular implementation

of nature’s coin toss is

fair.

Calibration: Counts

per minute reflect the Geiger-Müller tube’s sensitivity and possibly

also how it is packaged. To convert counts to physical units (radiation

dose) it is necessary to calibrate the counter. Even if calibration

were not needed it would still be fun to construct this option because

it makes use of all five button press directions: north, south, east,

west, and center.4

On first entering the calibration option the digit to the left of the

decimal point is highlighted. Pressing up (north) or

down (south) increases or decreases this digit’s value, with rollover between

‘9’ and ‘0’. Pressing left (west) or right (east) moves editing to the digit on the

left or right of the one that is currently being edited. When editing

is complete, pressing center (pushing the button straight in) causes the ‘Save and return’

option to be highlighted. On accepting this option (another center press) the

edited value takes effect immediately, and is saved to EEPROM to be

restored whenever power is

cycled. To exit the calibration option without saving, press ‘down’ to select the bottom option, and then center-press.

There are two ways to ascertain what the

calibration value should be—well

probably more than two, but two that I know about. The first is to use

a measured quantity (source) of radioactivity. Precisely position

the source in relation to the G-M tube and record counts per minute over a

sufficient interval. Finally, subtract out the background and apply

some seriously imposing

formulas to the balance. The other way is to place the unit in the same location as a calibrated

(trusted) instrument and compare readings of the same source, e.g.,

background radioactivity, again over a suitable time period.

Clearly the latter method is less challenging, and should normally

suffice, given that the project is intended for

entertainment, not for scientific work, and most assuredly not for use in a

radiation safety application.

Other

menu options: The

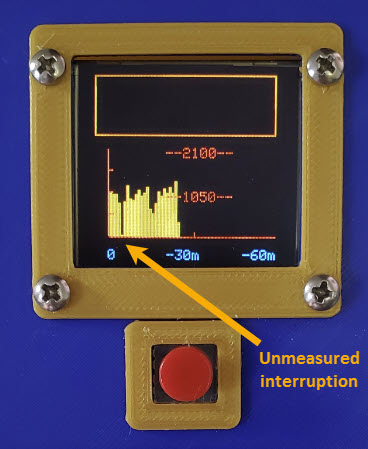

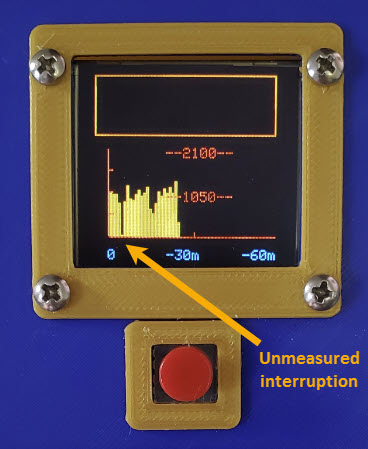

‘Last Minute’ option displays a histogram (photo left) of

second-by-second moving average counts per minute, with the current

time’s count at the left (0-seconds) and the count for one minute

prior at the right-hand end (-60s). This same graph can be displayed for two-seconds from the main screen by pressing ‘up’.

Other

menu options: The

‘Last Minute’ option displays a histogram (photo left) of

second-by-second moving average counts per minute, with the current

time’s count at the left (0-seconds) and the count for one minute

prior at the right-hand end (-60s). This same graph can be displayed for two-seconds from the main screen by pressing ‘up’.

The ‘Last Hour’ option is analogous, displaying a histogram of

extrapolated counts

per hour from the present (leftmost) to one hour ago (rightmost).5

Exiting from menu selection resets counters to zero. When

this

happens a bar is skipped in the hour graph, because the amount of time

spent in the

menu context was not measured. Thus, a missing bar in the ‘Last Hour’

histogram (photo right) represents a time interval of

unspecified duration. Bars to the right of the blank represent data at

least as old as indicated, but possibly older.

The 1½ inch OLED screen does not accommodate much in the way of detail.

To compensate for inadequate space, vertical axis tick values are shown

in the middle rather

than the left edge of the graph, where they would subtract from the

space available for plotting the graph. These reference values are scaled

according to the maximum count recorded during the time period shown.

For example, if say 40 counts are detected during the minute to be

graphed, the ‘Last Minute’ scale doubles to 70. Similarly it can expand

to 3 × 35 or 4 × 35, etc. The base value ‘35’ can easily be changed to reflect different detector sensitivities. It is a named constant in the sketch.

The ‘Random Hex’ option displays a table of random numbers in hex

format. As previously noted, random data

harvesting that relies on background activity is slow, so time is needed to fill out the table. If examined

soon after startup, the table will have

only a few non-zero entries. Consecutive zeros to the end of the table

represent unvalued cells, except by extraordinary coincidence! Perhaps dashes

would have been better for unpopulated cells.

In truth a small table of random bytes

is of little

use or interest, but something had to occupy available vertical

space in the options list! That said, I

did use the option myself, albeit artificially. Before

restoring a calibration number from EEPROM it would be good to know if

a valid calibration value has been stored there. Otherwise EEPROM

might contain only junk, in which case a

default constant should be used instead. So I added a four-byte key

to sign the stored value. That stored constant key came from the

program’s own random generator—a meaningless but appealing self-reference.

Serial

data: In order to study long-term

background radioactivity, or for

that matter any source of activity, it is necessary to capture data for

analysis. To do this, connect the device’s USB jack to a computer USB

port, the same as when programming the Arduino. The counter’s

serial data stream can be displayed via the Arduino

IDE’s serial monitor or PuTTY or Termite or any such serial COM

utility. Textual data can be captured to the

clipboard or saved to a file. From there the data can be imported to a spreadsheet

application or to statistical analysis utilities, and so forth.

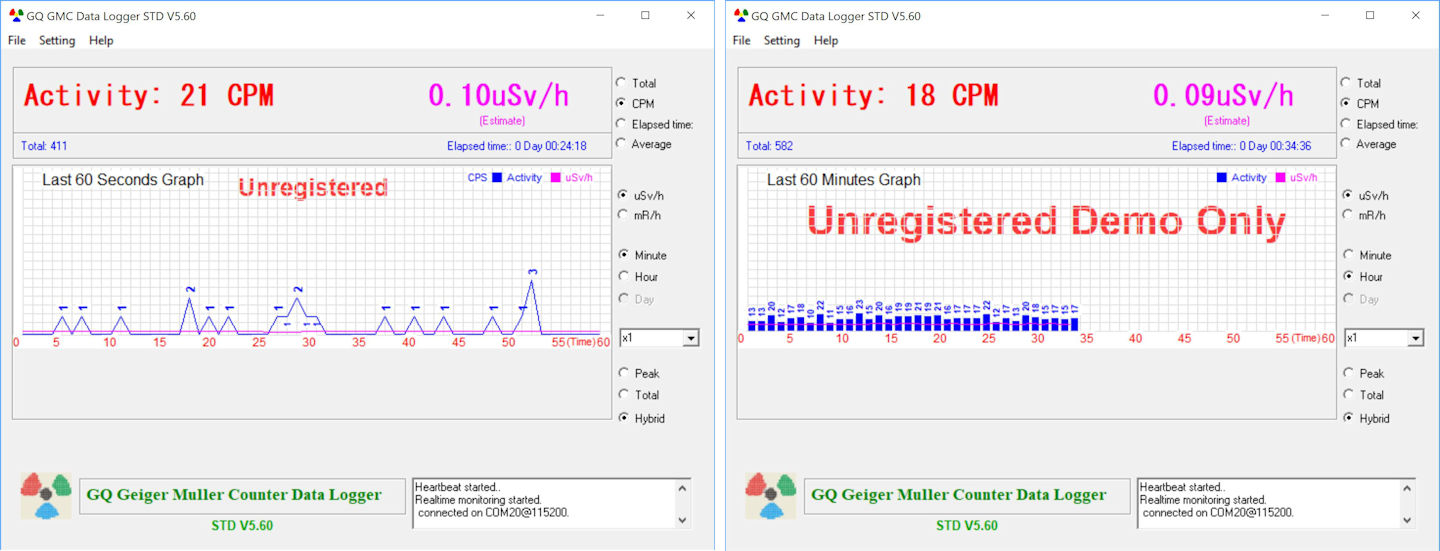

RFC1201:

A company called GQ Electronics sells

Geiger Counters in several models, and offers their GQ GMC Data Logger application

software for download. The interface specification is an RFC.

It is possible to register GQ

Electronics Data Logger software, although I have not done so. The

application is almost surely designed for interfacing with the

company’s own Geiger Counters, but can be interfaced with other units

as well, at least partly so. The project Geiger Counter’s

microcontroller is coded to respond appropriately to documented start

and stop heartbeat commands: <HEARTBEAT1>> and

<HEARTBEAT0>>. These commands start or stop the real-time

upload

of counts per second. As this feature is implemented in the present

project, the Geiger Counter sketch transmits a constant as the first

byte and the count (up to 255) as the second byte of the heartbeat, not

a 14-bit datum as specified in the RFC, but good enough—I hope never to

detect more than 255 counts per second with this counter! In any case,

the format works. Received ‘heartbeat’ counts effectively enable graph

and activity

display features of the Data Logger, with limitations.

In the above screen captures, the Data Logger

application was receiving and displaying data from this project’s

Geiger Counter, not one of the GQ Electronics models, which are

admittedly much nicer. But as I said there are limitations. My sketch

(download link below) does not honor a time sync request from Data

Logger, not yet anyway. Thus, after about an hour the application

displays the message “Time Sync Failed! Task rescheduled within 30

seconds.” However, the program continues to receive and display counts.

Another caution is that the displayed ‘estimated’ dose value does not

reflect the sensitivity of the unknown counter that was interfaced.

Thus the displayed estimated dose is not valid in this context. I do not know if Data

Logger’s dose calculation can be calibrated for an unlisted instrument.

In truth the main appeal of this application was its colorful

appearance. For any sort of meaningful study it would be advisable to

upload raw values, and select a suitable analysis utility from the wealth

of such tools that are available.

Concluding thoughts: The Arduino Mega microcontroller code is

available for download as a zipped folder: Geiger sketch and bitmaps.

Component interconnections do not require a

diagram, as they are documented by pin numbering in the sketch. In any

case

this write-up is not intended as a ‘How to’ reproduce what I did (there

are better models to follow), rather as a story about having fun with

the popular open-source Geiger Counter board. Other similar projects might aim for a more practical or

useful result than the construction described in these paragraphs.

1. Adafruit’s GFX

library (1.4.2) default font does not include the Greek letter

mu.

(Lowercase μ stands for ‘micro’ as in microsecond or microsievert.) Nor

was the character to be found elsewhere in the library’s fonts folder.

Well, there was one font (not sure if it is part of the library or an

add-on) called TomThumb, but I couldn’t get that one to work at all.

Small things are sometimes the most distracting. I spent probably two

days attempting without success to construct a GFX-compatible font that

included the letter mu. But then the realization dawned that mu stands

for ‘mirror u’ (joke). This thought led to a shameless

kludge that consisted of printing ‘u’, then erasing and drawing

pixels to reverse the English letter’s base. And since μ always follows

space

in the display I added a tick at the letter’s starting cursor position

-1 to curve the new left-side

stem, a sure giveaway to any font-sensitive eye.

2. This, of course, says nothing

about possible bias in the mapping of elapsed time to parity. However,

flipping the meaning of the timing function’s mapping, i.e., the

meaning of (microseconds (mod 8) == 0), on successive

invocations of the function should counter built-in bias. I got this

idea from https://www.fourmilab.ch/hotbits/how3.html,

where, in addition to flipping the parity mapping, time deltas are

used—intuitively better, but slower.

3. Only one coin toss can be harvested in a given second by the method

described. No clicks means no coin toss. Multiple clicks in the same

second yield just one toss. Thus, relying only on background

radioactivity, bit-harvesting by the method of this project is

impractically slow.

4. The Radio Shack

#27801 (Parallax) 5-position switch also supports combinations of

directions

for a total of 18 states. However, only primary button presses were

used in

this project.

5. The actual counts per hour (CPH)

value cannot be known until at least one hour has elapsed. Thus, the

CPH graph depicts minute-to-minute estimated rates, computed by summing

CPMs over each second of the preceding minute..

Project descriptions on this page are intended for entertainment only.

The author makes no claim as to the accuracy or completeness of

information presented. In no event will the author be liable for any

damages, lost effort, inability to carry out a similar project, or to

reproduce a claimed result, or anything else relating to a decision to

use the information on this page.

Heads

or

tails: It is possible to purchase an attractively

packaged pre-made Geiger Counter, for example this one,

for not much more than the cost of

this

project’s

parts. The main

reason to build or assemble a Geiger Counter is to personalize the

design, in other words to express whatever crazy ideas

come to mind. One such idea was to include a graphical coin toss

option. This idea was partly inspired by the resource described on this page,

which dates from 1996 (impressive!). I had played with the ‘physical

random numbers’ idea previously, but in a project that used electronic

white noise as the source of randomness (write-up here).

Heads

or

tails: It is possible to purchase an attractively

packaged pre-made Geiger Counter, for example this one,

for not much more than the cost of

this

project’s

parts. The main

reason to build or assemble a Geiger Counter is to personalize the

design, in other words to express whatever crazy ideas

come to mind. One such idea was to include a graphical coin toss

option. This idea was partly inspired by the resource described on this page,

which dates from 1996 (impressive!). I had played with the ‘physical

random numbers’ idea previously, but in a project that used electronic

white noise as the source of randomness (write-up here).

Other

menu options: The

‘Last Minute’ option displays a histogram (photo left) of

second-by-second moving average counts per minute, with the current

time’s count at the left (0-seconds) and the count for one minute

prior at the right-hand end (-60s). This same graph can be displayed for two-seconds from the main screen by pressing ‘up’.

Other

menu options: The

‘Last Minute’ option displays a histogram (photo left) of

second-by-second moving average counts per minute, with the current

time’s count at the left (0-seconds) and the count for one minute

prior at the right-hand end (-60s). This same graph can be displayed for two-seconds from the main screen by pressing ‘up’.