NOAA GOES-16

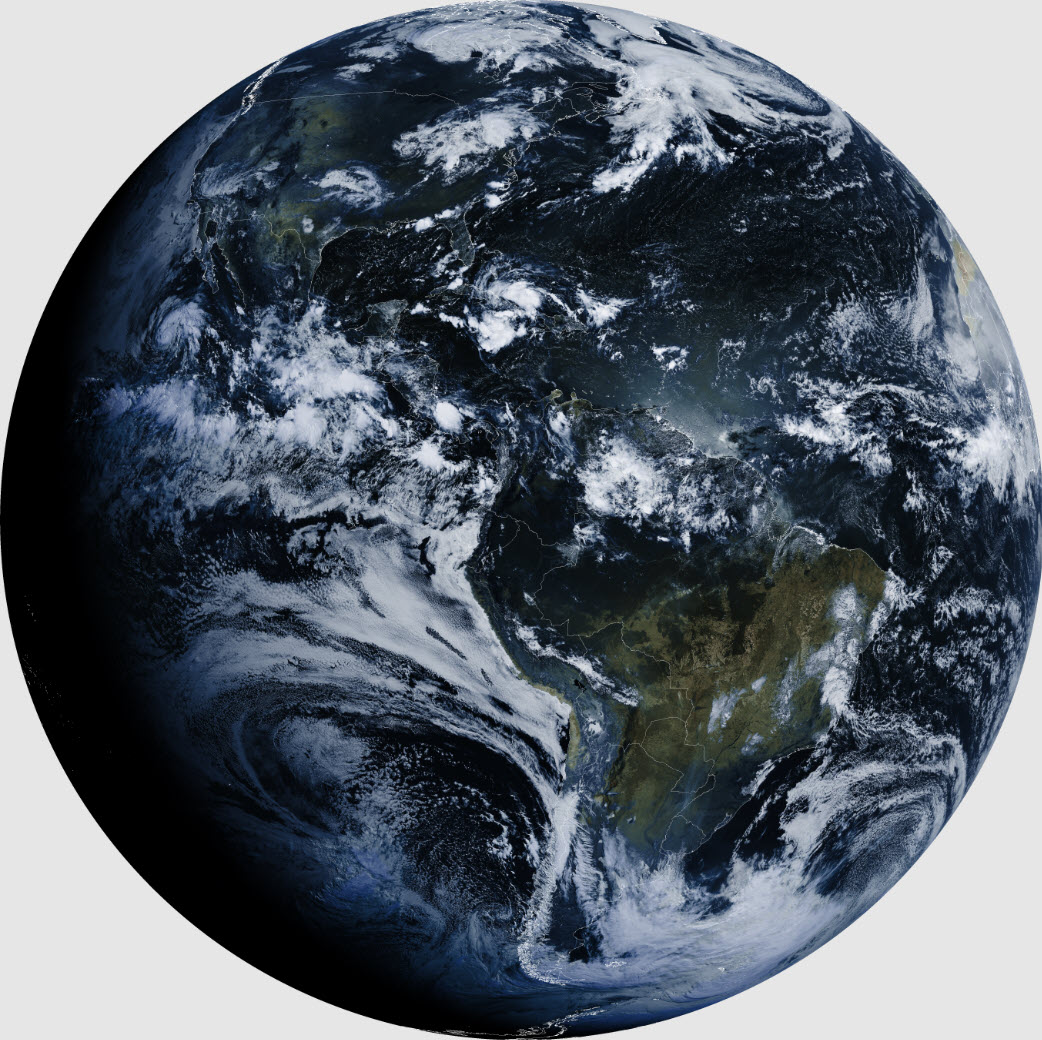

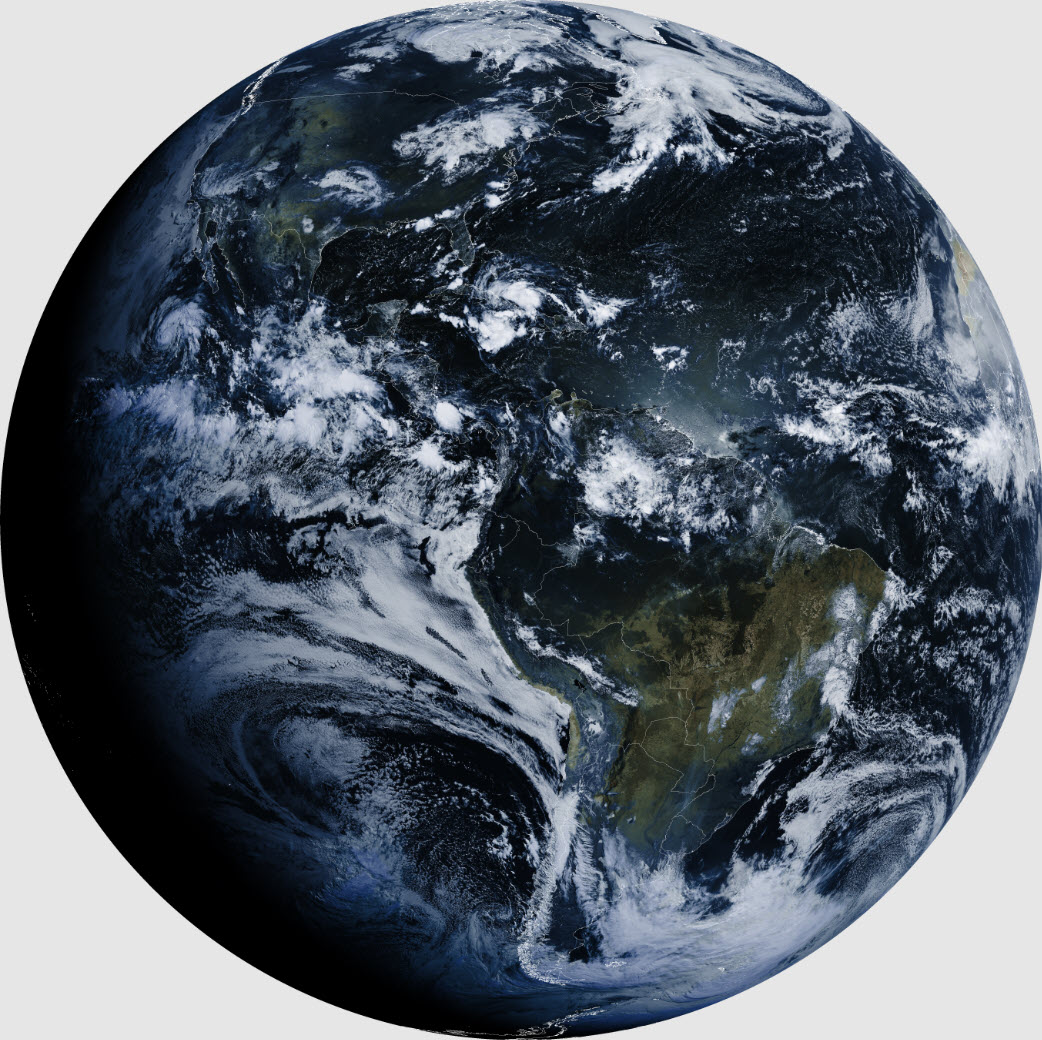

Getting started: The .jpg image above does not do justice

to the original high-resolution .png from GOES-16. Click the

link and zoom-in to view amazing detail.1

Before describing how this

image and many others were successfully received and decoded I will

briefly recount the highlights or lowlights of my first attempt to

receive GOES-16 in October 2018. A previous owner of our house had

abandoned a

DirecTV dish in the backyard. I kept the steel post and

azimuth/elevation mount,

but replaced the TV dish with one that was said to be good for

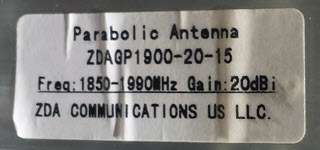

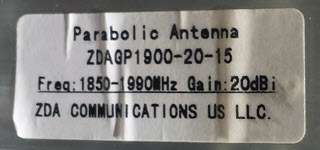

receiving the NOAA GOES satellite. The antenna that I purchased was

manufactured by ZDA Communications, and labeled 1850–1900 MHz, about

200

MHz above the frequency of interest. This first attempt at GOES

reception was doomed, not on account of the antenna, but rather of my

failure to understand or fully appreciate the nature of the challenge.

Getting started: The .jpg image above does not do justice

to the original high-resolution .png from GOES-16. Click the

link and zoom-in to view amazing detail.1

Before describing how this

image and many others were successfully received and decoded I will

briefly recount the highlights or lowlights of my first attempt to

receive GOES-16 in October 2018. A previous owner of our house had

abandoned a

DirecTV dish in the backyard. I kept the steel post and

azimuth/elevation mount,

but replaced the TV dish with one that was said to be good for

receiving the NOAA GOES satellite. The antenna that I purchased was

manufactured by ZDA Communications, and labeled 1850–1900 MHz, about

200

MHz above the frequency of interest. This first attempt at GOES

reception was doomed, not on account of the antenna, but rather of my

failure to understand or fully appreciate the nature of the challenge.

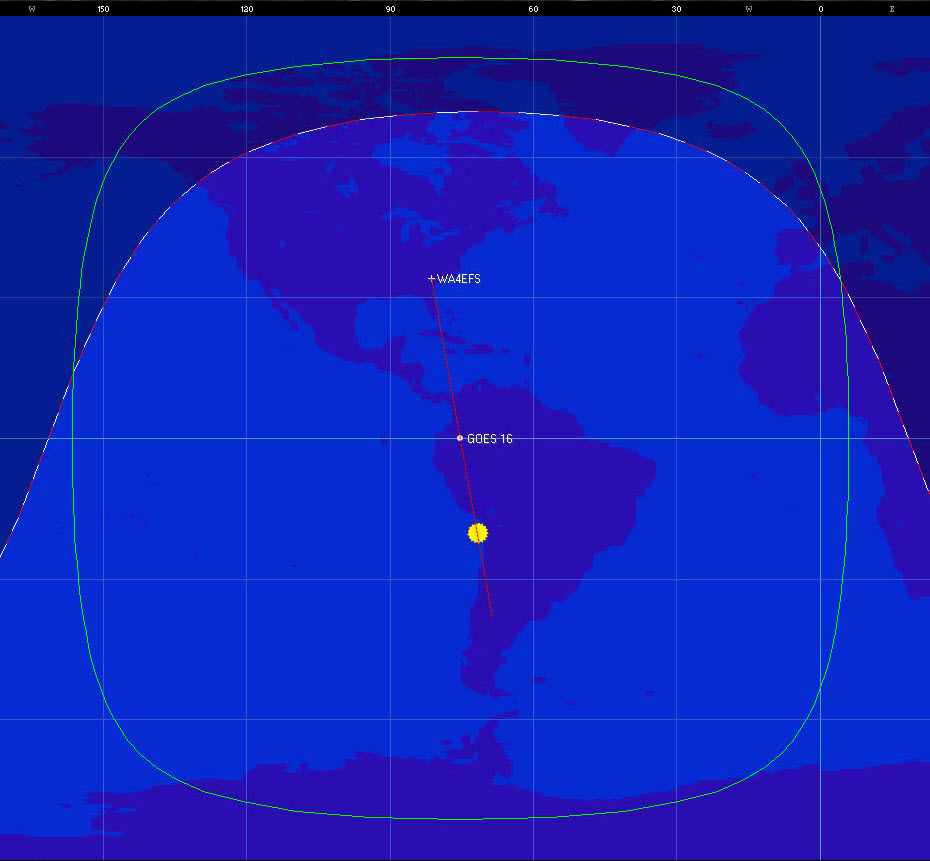

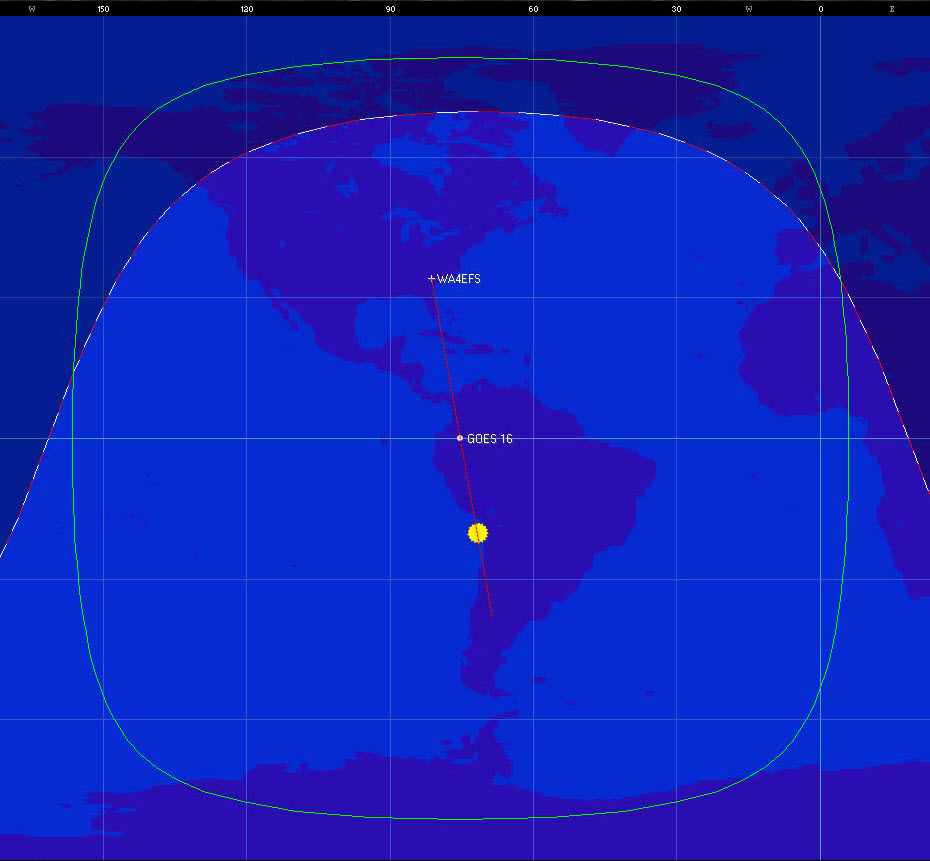

One unusual aspect of this first attempt to receive

GOES-16 was the method of aiming the antenna’s azimuth (bearing from

the antenna to the satellite). I used the satellite tracking program Orbitron to show the time of day that

the sun would share the same bearing as the satellite from my location.

I then

aimed the

antenna toward the sun at that precise moment.

This felt like a clever idea at the time, but it

did not lead to success. Many factors in addition to the antenna’s

azimuth influenced the outcome of this first effort to receive the GOES

satellite.

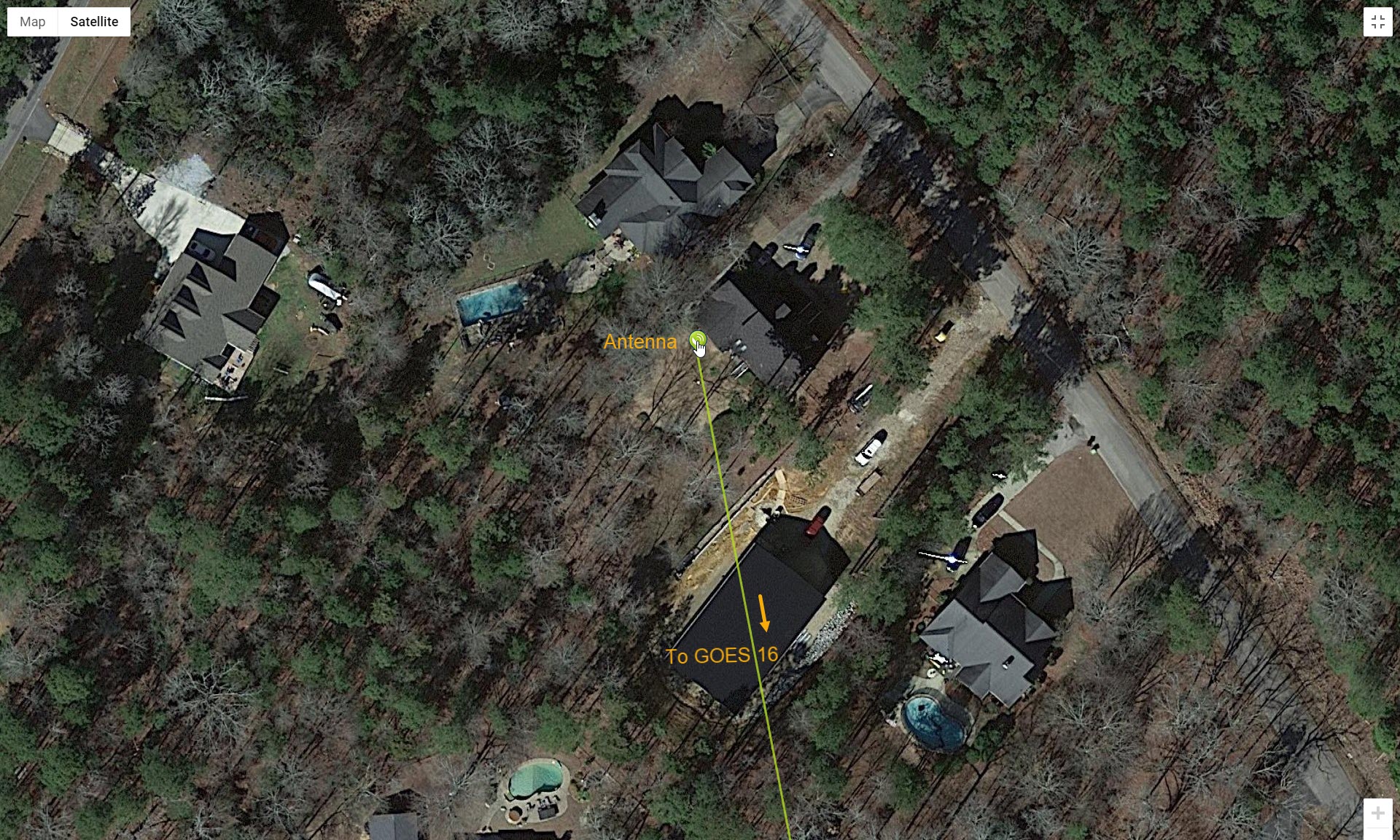

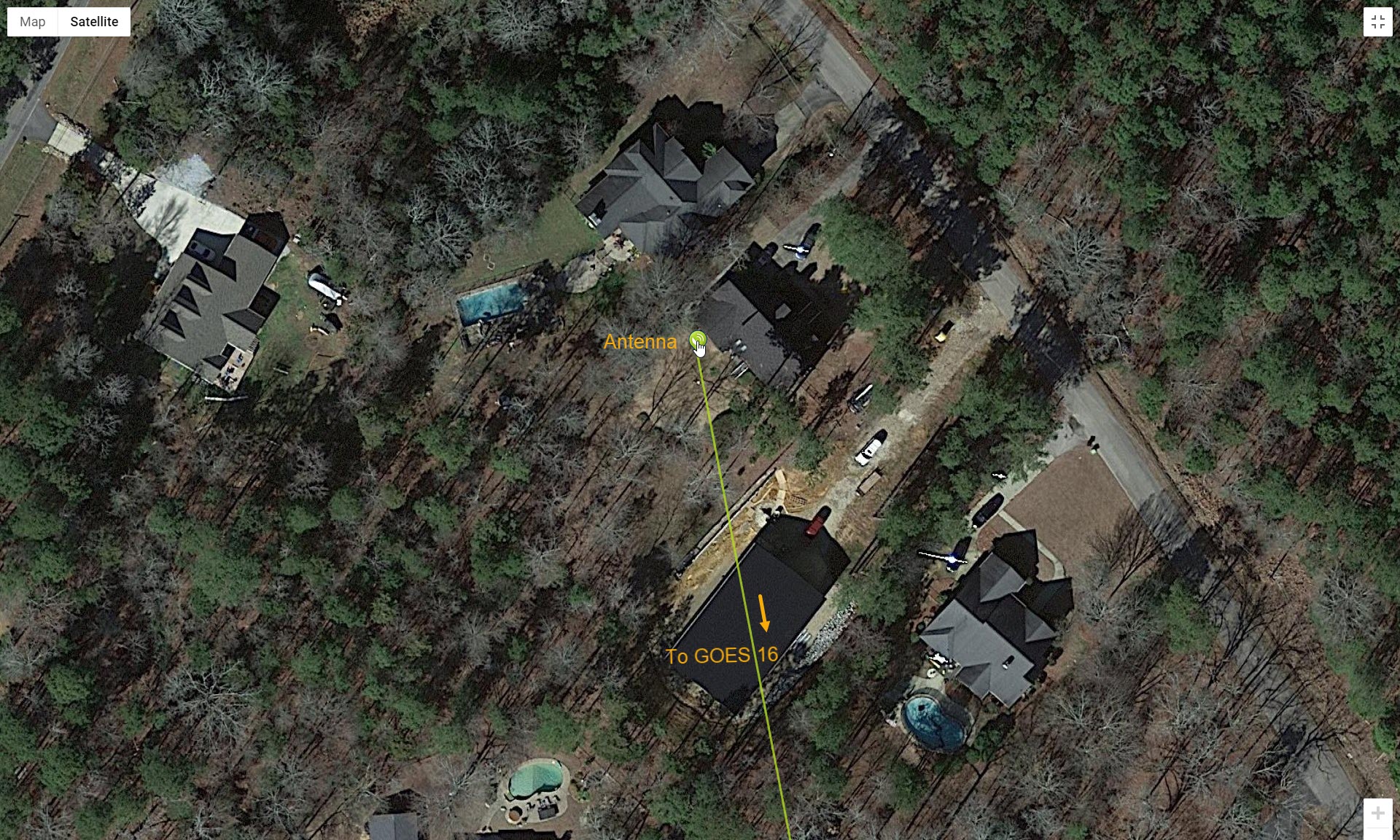

Recently I learned about a fantastic resource

for aiming a dish antenna:

https://www.dishpointer.com/.

This Internet site not only calculates azimuth and elevation

for a selected geostationary satellite, but also

draws a line over a Google image of the location, showing

exactly which way to aim the antenna (photo above).2

Aiming across the neighbor's shed at the indicated point was easier and

surer than using a compass. Moreover, there was no hurry, because

unlike the sun, the shed was not moving.

To adjust antenna

elevation angle, I used essentially the same procedure in 2018 as in

the

effort to be described on this page. Back then the tool set consisted

of a plastic protractor and small ‘pocket’ level; while for try #2, a

digital protractor and larger level were used. It was impossible to

photograph measurement while using the larger implements—not enough

hands. However, in each case the protractor was placed alongside the

‘boom’,

such that the

angle of the boom with respect to the horizon (bubble level)

could be

measured after each adjustment. The mounting mechanism, inherited from

the old DirecTV setup, displayed the same angle measure, and agreed

within a degree or so with protractor readings.

To adjust antenna

elevation angle, I used essentially the same procedure in 2018 as in

the

effort to be described on this page. Back then the tool set consisted

of a plastic protractor and small ‘pocket’ level; while for try #2, a

digital protractor and larger level were used. It was impossible to

photograph measurement while using the larger implements—not enough

hands. However, in each case the protractor was placed alongside the

‘boom’,

such that the

angle of the boom with respect to the horizon (bubble level)

could be

measured after each adjustment. The mounting mechanism, inherited from

the old DirecTV setup, displayed the same angle measure, and agreed

within a degree or so with protractor readings.

For the 2018 attempt to receive the GOES

satellite I used a 50 foot (15 meter) run of ordinary high-frequency

coax (RG-8X) from the antenna and LNA to an RTL-SDR inside the house.

This necessitated constructing an outboard biasTee supply and

interface, as the particular RTL-SDR used then was not capable of

supplying biasTee voltage. I won’t attempt to

enumerate all the possible reasons for failure of this first try.

Suffice to say that tuning the SDR around the satellite frequency never

once produced a whisper.

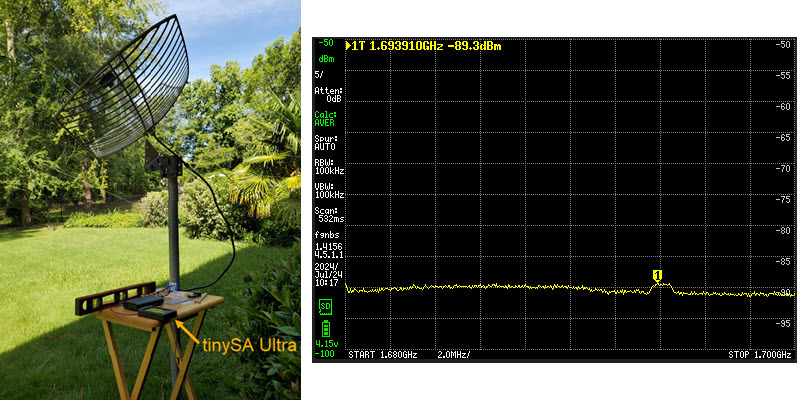

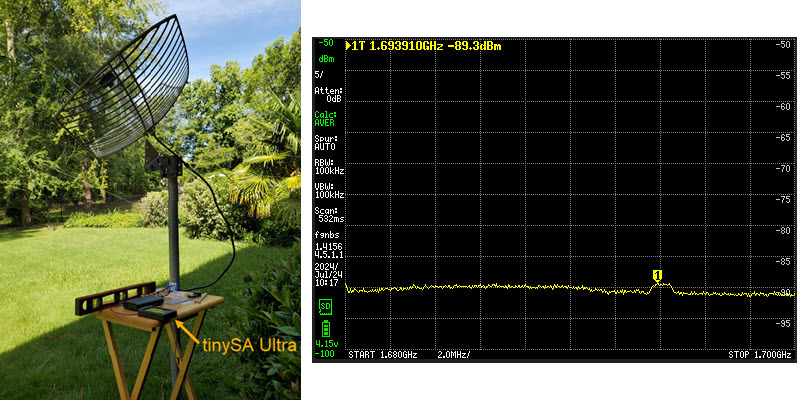

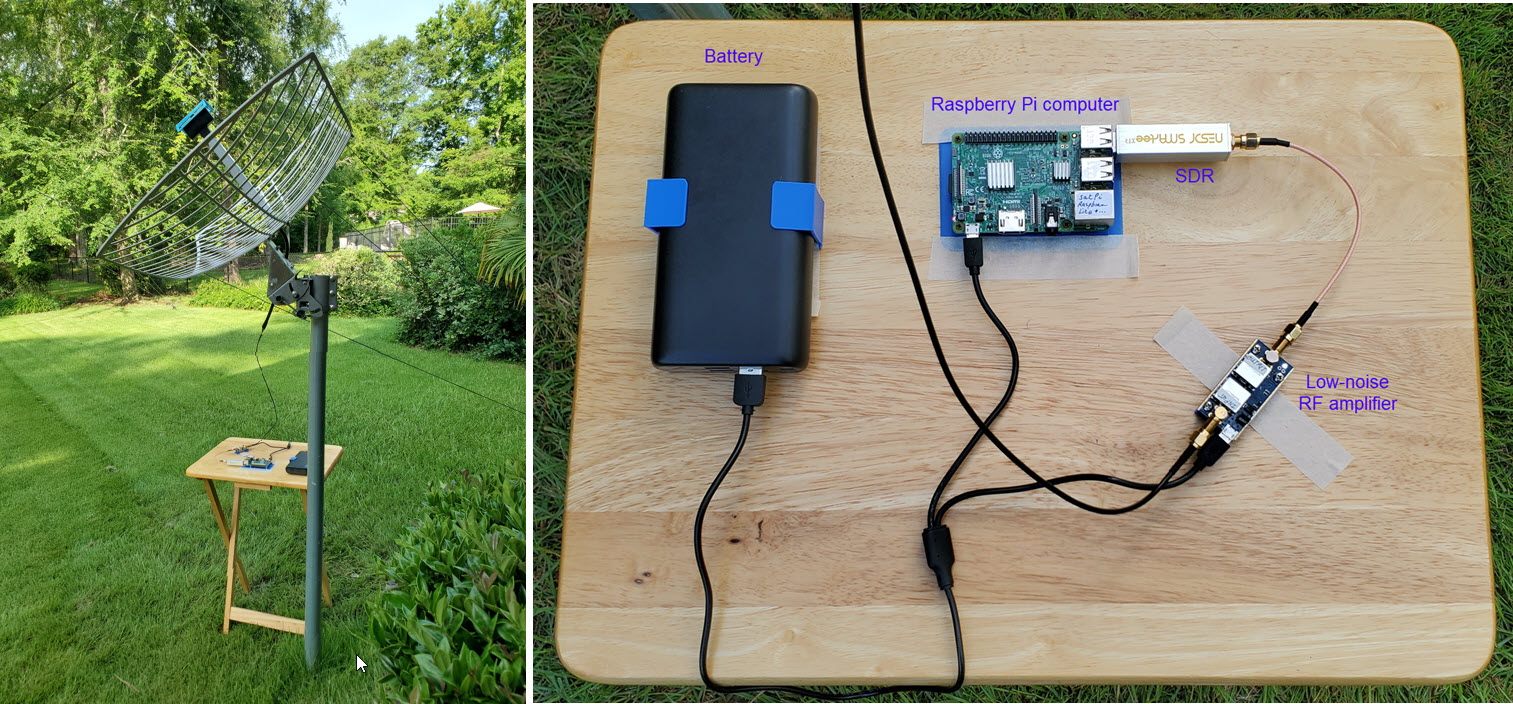

Try #2 (2024): This second attempt to receive

and decode GOES-16 was inspired by a simple idea. I had acquired a

tinySA Ultra (handheld spectrum analyzer) and was thinking about one of

its

extremely useful features. TinySA Ultra can be configured to average

successive sweeps, either a fixed number of times or indefinitely.

Averaging cancels most of the noise, causing the tinySA Ultra to

display a nearly flat line reflecting average noise

power. If there is a signal anywhere in the swept spectrum, it

will stand out in the average of many sweeps. The thought was that it

might be possible to detect GOES-16 using tinySA in averaging mode. If

such a try were to succeed, then it should also be

possible to improve the signal by experimentally manipulating anything

and everything that could be tweaked in the setup. As the above

screen-capture indicates, this sensitive signal detection method did succeed.

Note the 1 to 2 dB bump at the 1694 MHz

GOES frequency. The associated setup photo is

somewhat cluttered, but the antenna connects to a battery powered LNA,

which connects via a short coax jumper to the spectrum analyzer’s

RF input.

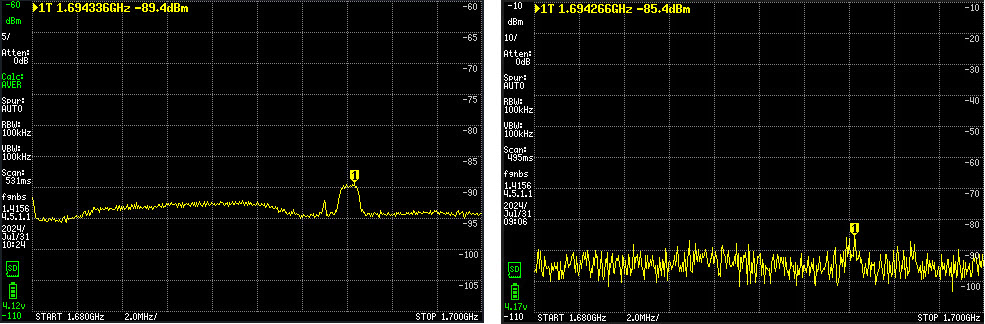

Starting from a small bump in the tinySA average of

many sweeps, I tweaked azimuth and elevation and even the spacing

between the secondary reflector and feed (boom), as was suggested in

this informative tutorial. However, inverting the small

reflector made no difference. I did not adjust the antenna’s skew—That

would have been tricky with my makeshift mount adapter. Some

adjustments seemed to help a little, but none made the signal stand out

in real-time (not averaged) sweeps of the 1.68 GHz to 1.7 GHz spectrum.

Having made only marginal progress I began to wonder

about the antenna, whether it was really capable of good reception at a

frequency that was substantially different from its design frequency.

Many others had reported positive results from this antenna, but I had

doubts. Then I did something that may have been foolish. I bought

another antenna.

The Nooelec GOES

antenna from Amazon advertised a center frequency of 1.7 GHz and

the label on the boom clearly confirmed this

advertised specification, although my nanoVNA rendered a different

opinion...

Nevertheless I proceeded to substitute this antenna for testing. The

Nooelec appeared physically identical to the ZDA 1.9 GHz dish. The

mount attachment was the same, so it was an easy swap.

In spite of my pessimism the signal was unmistakably

better from the Nooelec antenna, other things being equal. In fact the

GOES signal could also be seen in a real time sweep (right image

above). Knowing a signal was there (marker 1) might have helped. At

last there was hope of receiving something from GOES, probably not

much, but possibly a proof of concept. It was time to substitute an SDR

for the tinySA.

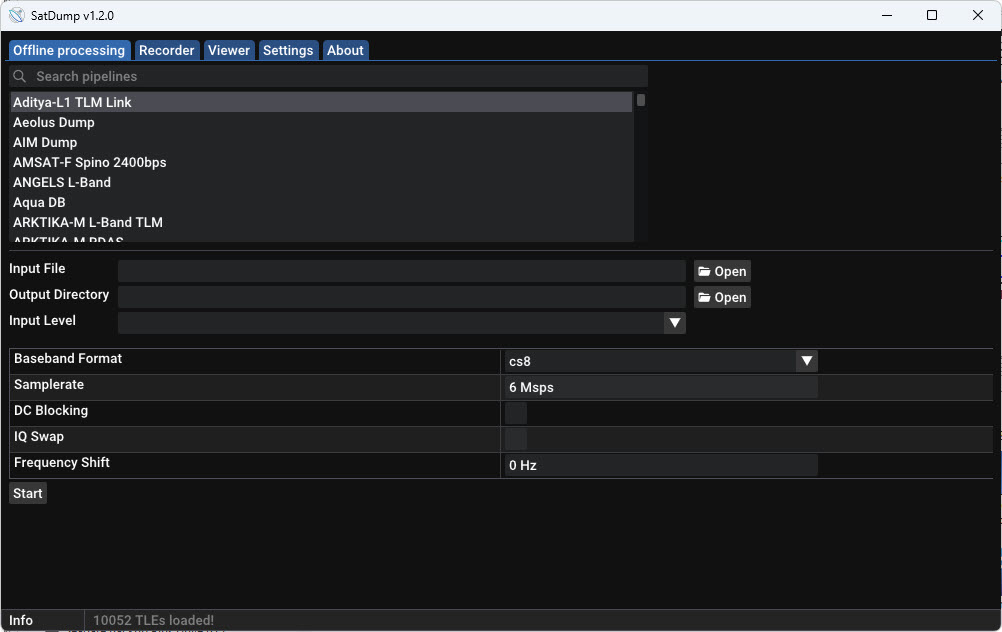

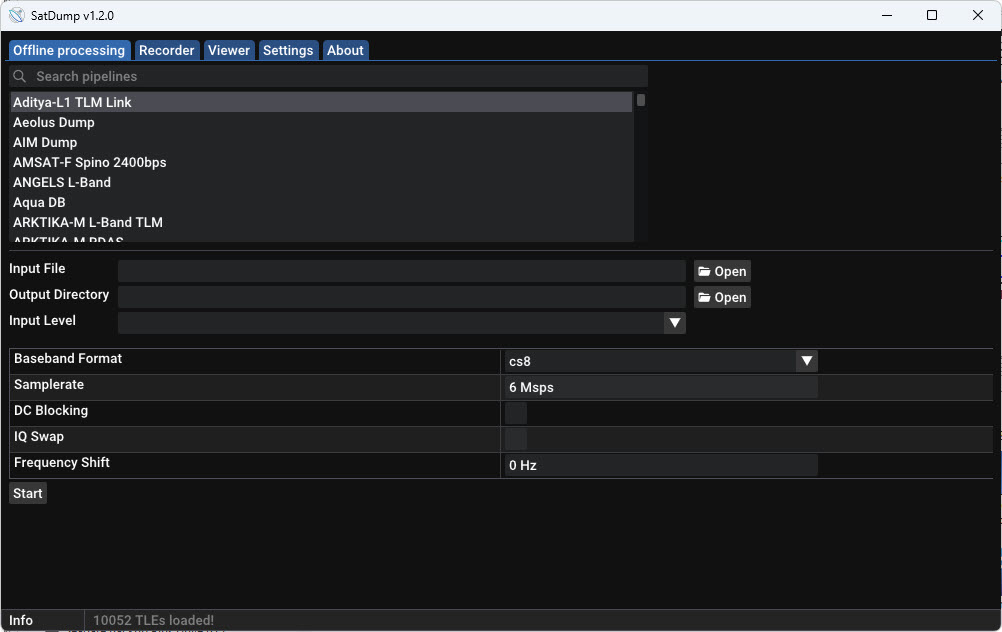

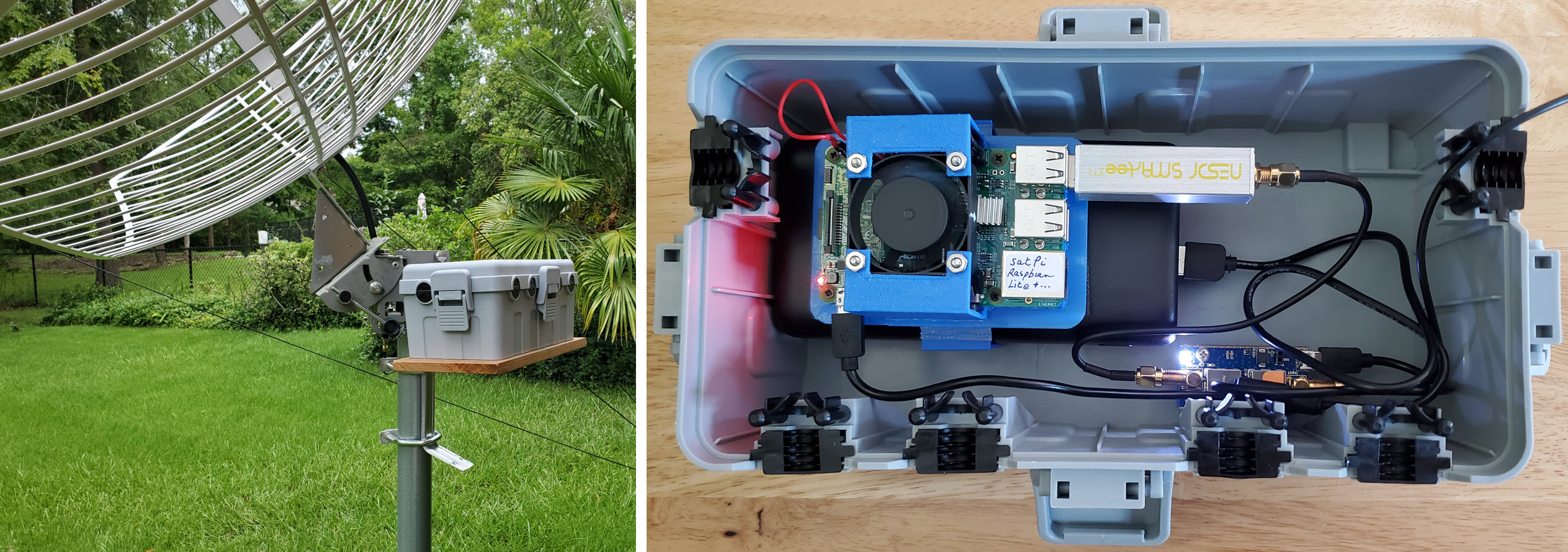

Receiving and Decoding: Up to this

point I had given little thought to the

next phase. I was only dimly aware of various software options for

decoding GOES transmissions. My thought was to run the LNA output to an

SDR on the desktop computer, using RG-8X coax, like in the 2018 try.

Anticipating this approach I installed SatDump

on the computer (screenshot above), but continued to seek and

read additional information on the general subject. This background

research led to another fantastic resource: https://usradioguy.com/receiving-goes-hrit-with-satdump.

Among its many useful suggestions, this article advises to install

SatDump

on a Raspberry Pi. Immediately I realized that doing this would

eliminate the need for a coax run between the antenna and my desk (or

anywhere). With luck it would be possible to place the Raspberry Pi

outside next to the antenna and operate the program via an SSH terminal

connection.3 Several Raspberry Pi’s

were on-hand, so I picked one to use for this purpose.

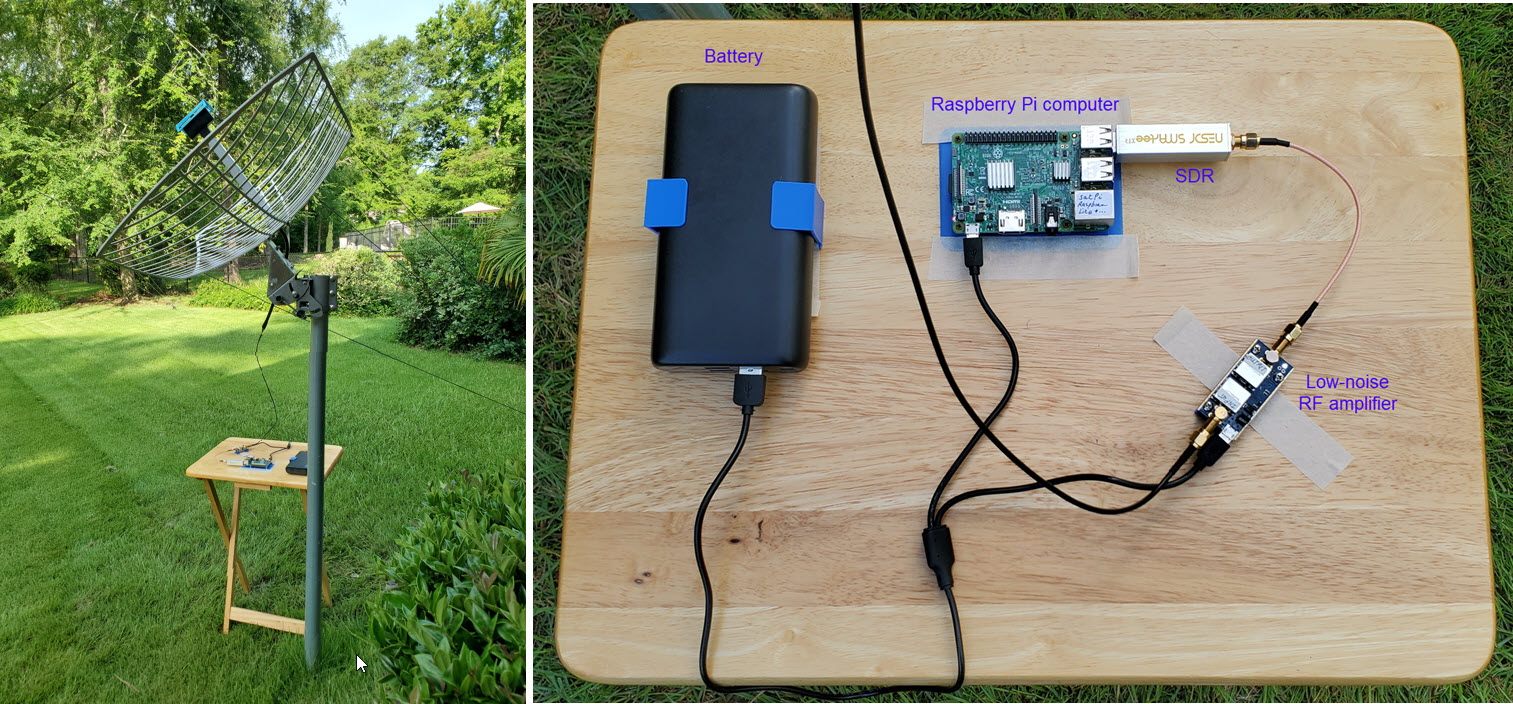

Following guidance from the ‘usradioguy.com’ web

page, I built a Raspberry Pi-3B command-line SatDump install on a small

capacity microSD. GOES data (if any were received) could be transferred

to my desktop from the microSD, thus not burdening the Pi with any

appreciable data storage requirement. I didn’t expect to receive much

data. In truth, I didn’t expect to receive any image data, imagining that the

signal was simply not strong enough.

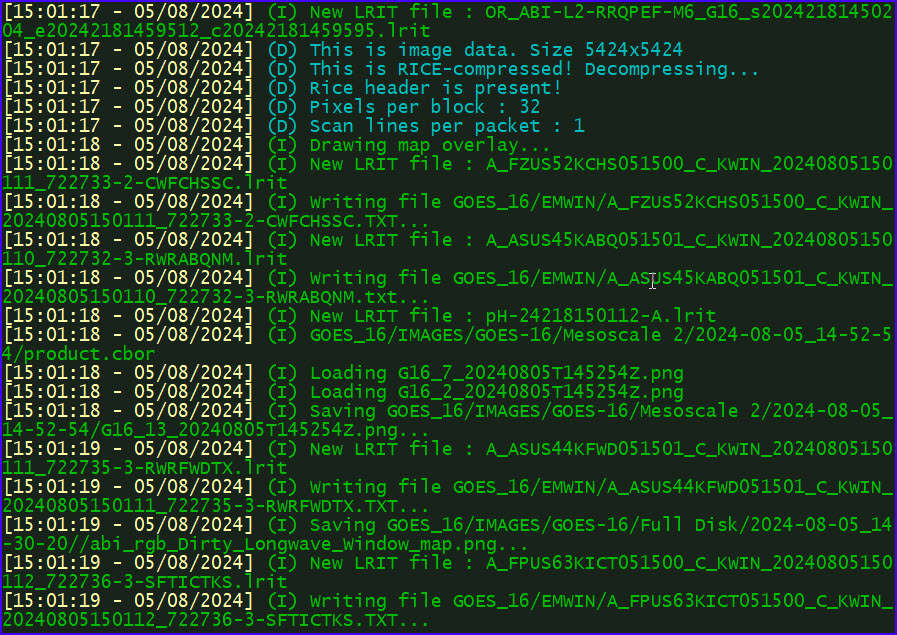

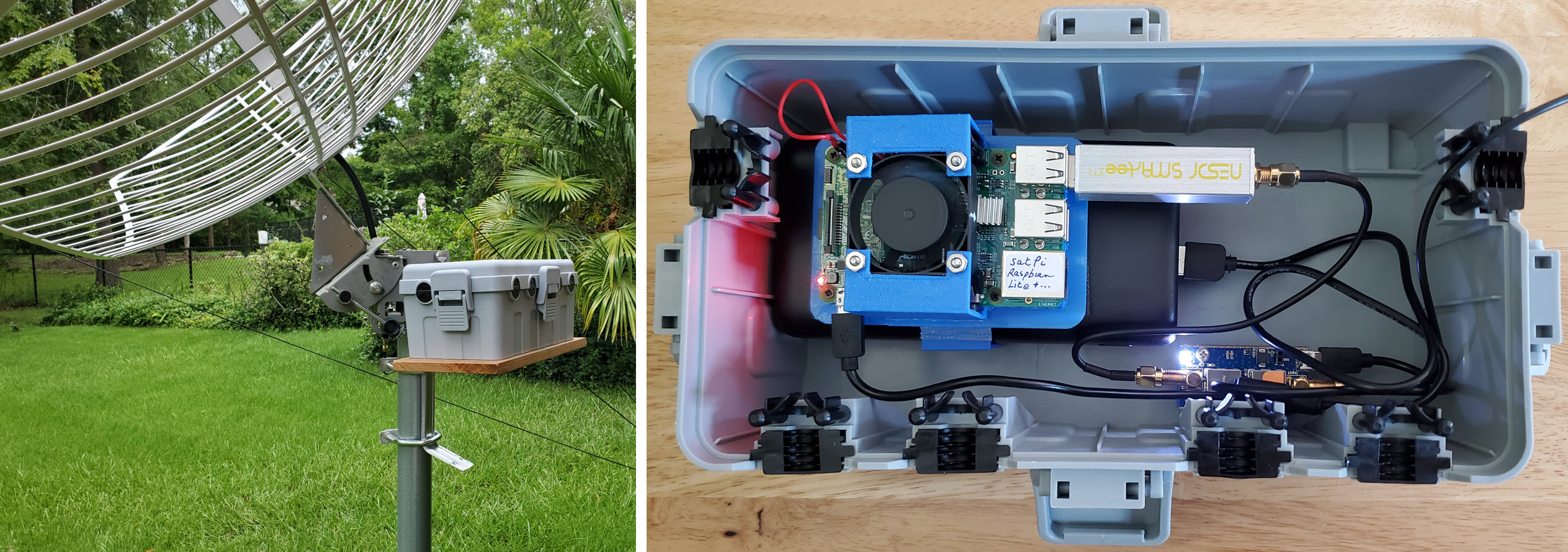

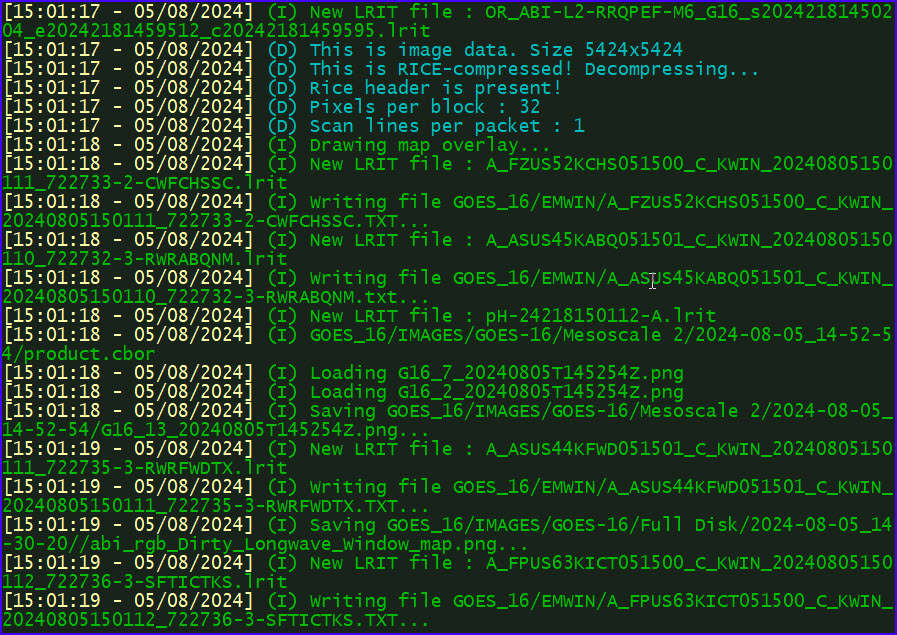

To my astonishment the very first test run of the

remote Raspberry Pi setup pictured above produced many clean text files

and several partial images. Some smaller images were nearly

intact. In the previous tinySA testing phase I had used three different

LNA / SAW filters, procured at different times in the past. One of them

seemed to produce relatively the same signal to noise at a few dBm

lower that the other two, which were indistinguishable from one

another. There would be no harm trying the one with lower power output

in the data acquisition setup. After making this substitution I got

nothing at first. However, informational messages from SatDump

suggested that the gain was too low. On increasing gain, a miraculous

result occurred. Decoding became error-free. All those red lines were

gone from the SatDump log. Even the largest high-resolution images were

perfect. How could that be?

Before this first data acquisition run with the

lower-output LNA/SAW filter, I had made a list of five things to try

for

improving the signal. Now there was no need to proceed to item #2 on

the list. After making one single change, the LNA/SAW filter swap,

SatDump reported zero errors. This performance was sustained in

many hours of additional decoding, over more than a week. (One

red line displays on first starting the program, where it begins to

receive data at a random point, e.g., in the middle of a file—after

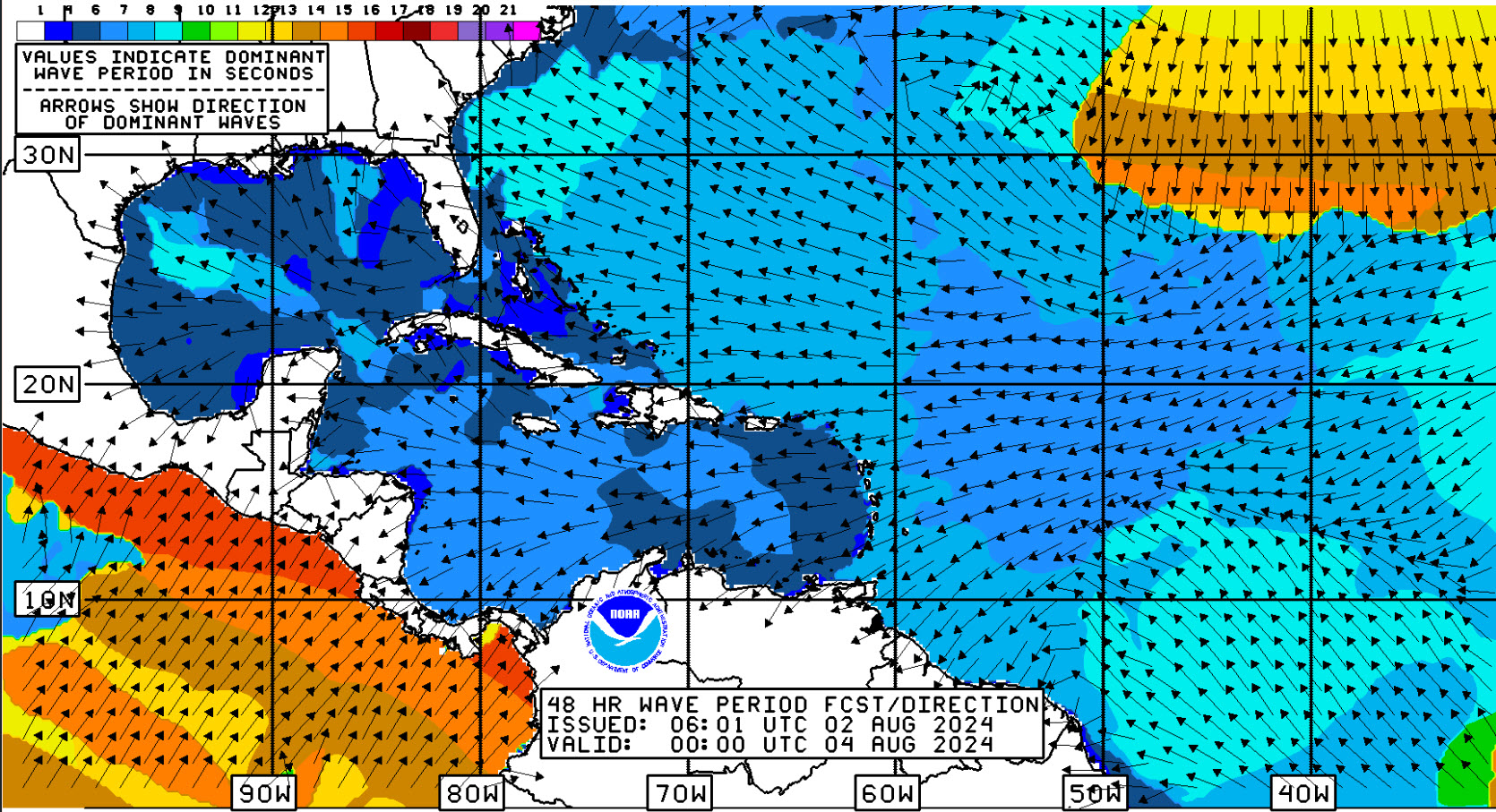

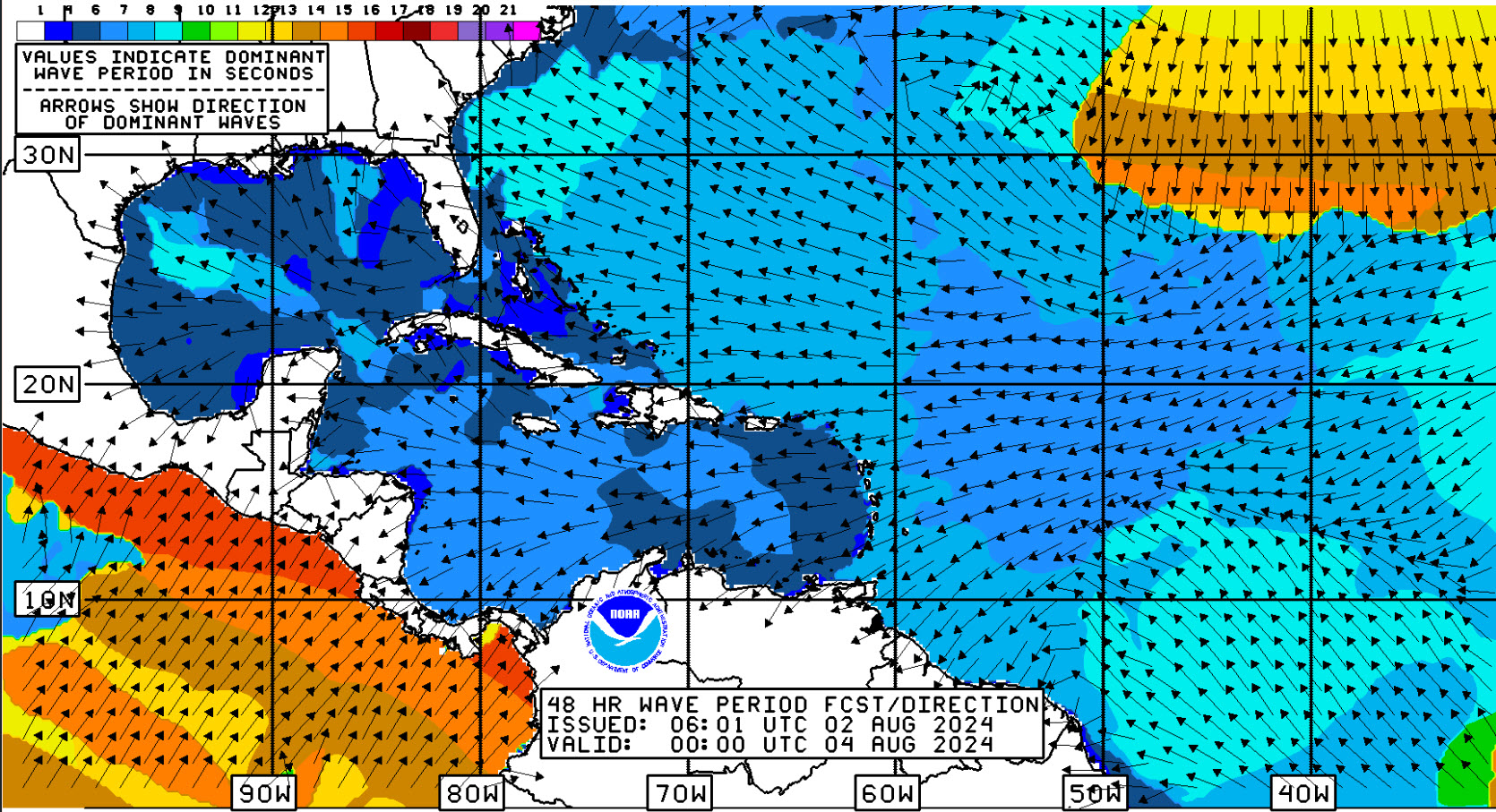

that, few or no additional errors.) A typical data acquisition session

lasts

about 80 minutes (an arbitrary interval), during which time voluminous

data are acquired—too much to review meaningfully. In addition to

hundreds of forecasts and satellite acquired photo images there

are also National Weather Service charts, such as the colorful example

below.

The quantity of data received and decoded would

resist meaningful analysis and review, except by meteorological

professionals, certainly not by me. TV weather forecasts and

our backyard weather station provide entirely satisfactory practical

information. The appeal of acquiring forecasts and

beautiful images directly from the NOAA GOES satellite is not so much

for their usefulness as for the satisfaction of having made the

exercise work. For the most part I have merely followed ideas and

suggestions published on-line by others. Still this NOAA GOES project

was a challenge, and one that yielded a pleasing reward for modest

investment.

Addendum 1: A folding table with taped-on components is

of no use when it is raining. I was curious whether GOES data would be

received through the rain and

clouds of tropical storm Debby, which meandered slowly northward, close

to our location on August 8, 2024.

The dry box is approximately 10½ inches long × 5½

inches wide by 5 inches in height. There is plenty of room for GOES

project components. However, short coax jumpers are stiff and awkward

to fit, so

I used a longer more flexible jumper between the

LNA and SDR. The fan in the photo is another story. It was not needed

on August 8, when the temperature was 72° F. (22° C.)—I will

return to the cooling concern.

Rain fell for 24 hours, sometimes heavy, other times

light. In early afternoon this high-resolution image of the hemisphere was

received. Both Debby and Emilia (Pacific storm) are clear in

the zoom-able image, which was timestamped 16:30 UT on August 8, 2024.

The antenna is situated near the south wall

of the house, leaving the dry box in shade until early afternoon. Of

course, when it is not raining, the top can be

left off the box. Nevertheless, it seemed

prudent to take steps to prevent overheating the electronics.

Unfortunately I

know nothing about the technicalities of cooling. Intuitively, though,

it

would be necessary to exchange air between

inside and outside the sealed box.

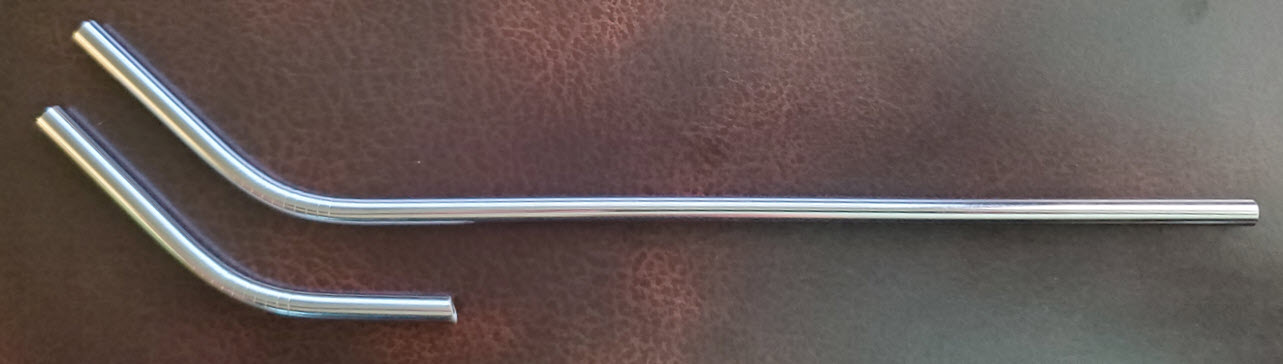

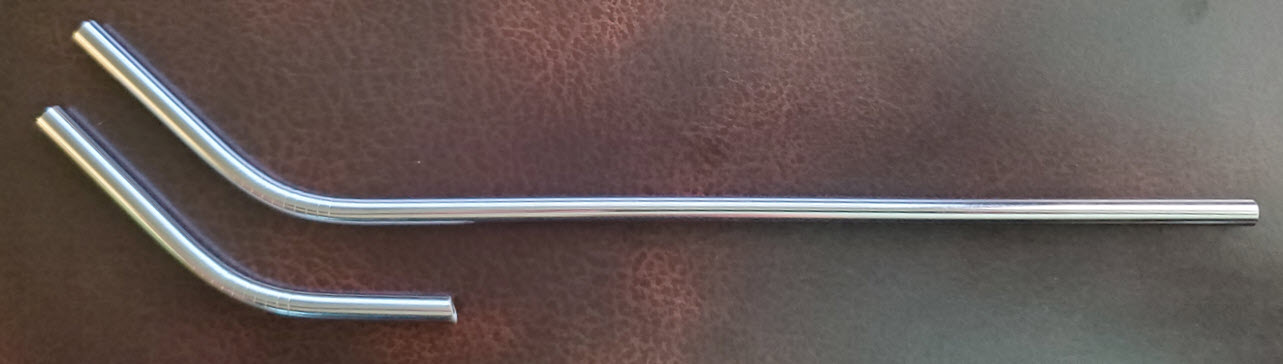

Drinking straws are about the same diameter as power cords, and should

fit through the dry box’s water-resistant openings. I purloined a pair

of curved steel straws from the pantry and cut one of them with the

Dremel tool to test the idea. The curved piece fit snugly. According

to my admittedly poor intuition about such things, two

cut pieces placed at opposite ends of the box, and turned downward on

the outside, should allow moving air to pass out- or in- when the lid

is shut. This whole cooling business may be a pseudo-concern, as rain

falling on the lid must surely cool the inside air; and, as noted, if

rain is not expected, the box can be left open.

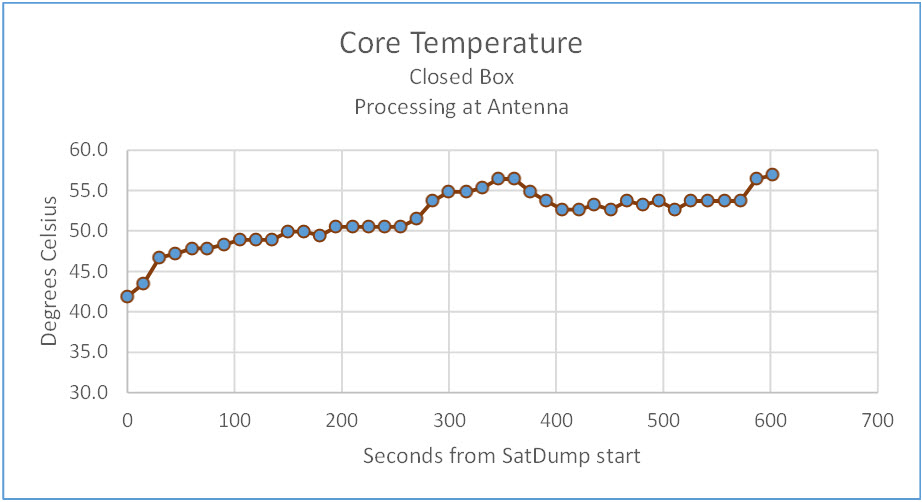

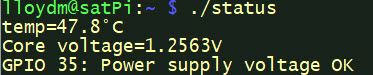

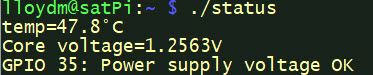

In any case, it is also reassuring that the Raspberry Pi has built-in

sensing of core

voltage and temperature. —I made a convenience script to format and

display these

parameters (image left).

Drinking straws are about the same diameter as power cords, and should

fit through the dry box’s water-resistant openings. I purloined a pair

of curved steel straws from the pantry and cut one of them with the

Dremel tool to test the idea. The curved piece fit snugly. According

to my admittedly poor intuition about such things, two

cut pieces placed at opposite ends of the box, and turned downward on

the outside, should allow moving air to pass out- or in- when the lid

is shut. This whole cooling business may be a pseudo-concern, as rain

falling on the lid must surely cool the inside air; and, as noted, if

rain is not expected, the box can be left open.

In any case, it is also reassuring that the Raspberry Pi has built-in

sensing of core

voltage and temperature. —I made a convenience script to format and

display these

parameters (image left).

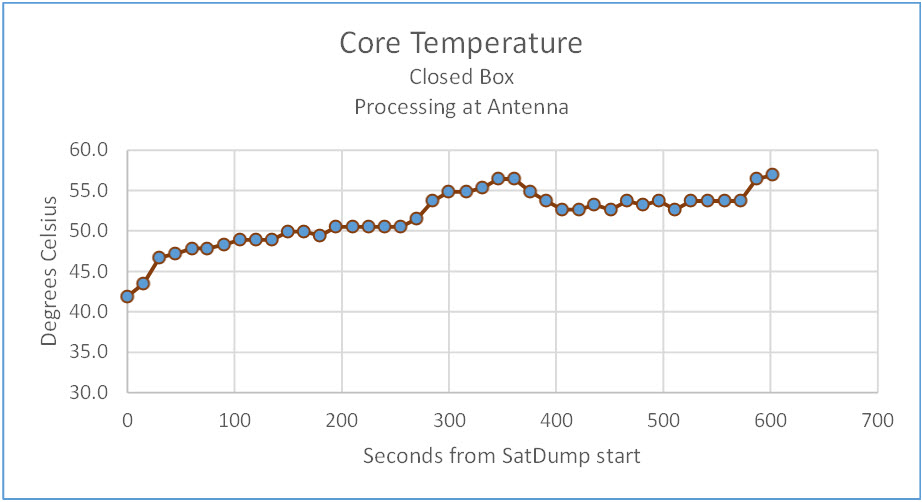

According to the Linux top command, SatDump accounts for

nearly 100% CPU when processing data from the SDR in real time. The

graph above shows temperature increasing over the first 10 minutes of

an example run, after which it stays around 60° C. for the remainder

of the session—Pi core is hot at 100% CPU.

Outside air temperature was about 90° F. (32° C.) and the sun was

beaming directly on the closed dry box. However, I don’t think outside

temperature matters a whit. What matters is processing demand. After

stopping SatDump, temperature quickly dropped to about 37°

C. and hovered around that value, even as the box remained in the sun.

Finally, as

far as I could tell, there was no appreciable air exchange between

inside and outside the box. My refrigeration engineering career is

on hold.

Demo video: My Goes Setup

Addendum 2:

GOES-16 transmits a ‘full disk’

image every half hour. My satellite reception/decoding sessions

generally last one to one-and-a half hours, sufficient time for two or

three high-resolution hemispheric images and a great many other files

to be received.

Full disk images showed more or less of the hemisphere in daylight,

depending on the time of

day each was acquired. The image timestamped 2100 UT seemed entirely in

sunlight. At that time no dark segments are seen, either east or west.

I began to think of collecting a full day of images, from

daybreak to dusk. Such a sequence would show the progression of

sunlight across the hemisphere, as earth and the geostationary

satellite turn.

Regrettably, the small capacity Raspberry Pi microSD

did not have

enough storage to accommodate a full day's data. I could have plugged a

thumb drive into one of the Pi’s four USB-A sockets, but elected

instead to build a fresh OS and application install on a 64 GB microSD.

On September 2, 2024, (Labor Day in the United States) I started

SatDump just before 5 AM local time (0900 UT) and let it run until

after 7:00 PM (2300 UT). Local weather was mixed, partly sunny but with late afternoon rain.

During this approximately 14-hour period more than 20,000 files (9.5

GB) were acquired. The data included 28 half-hourly full-disk images.

All were error-free.

The next day I converted the 28 images to a lower

resolution format and copied them to a video editor, in order to

experiment with various presentation parameters. For example, I

imagined a small analog clock in one corner (picture-in-picture), with

hour and minute hands indicating the time of each image. However, when

this idea was tested, the clock diverted attention from the satellite

images and had to be discarded. I also tested different presentation

durations, finally settling on three seconds per image. This was a

subjective assessment, of course. Three seconds felt comfortable and

made it easy to align the sequence with the selection of music that I

had in mind to use.

Demo video: Labor Day 2024

1. I have also uploaded a wallpaper version of

the image for 1024 pixel vertical resolution screens.

Right-click, SaveAs, etc. At the time this image was received it was

still night over the Pacific Ocean (leftmost part of disk). However,

the Raspberry Pi was barely in the shade and at 11 AM EDT (1500Z) the

temperature was already 90° F (32° C). The Pi might not fare well in

blazing summer sun. Keeping it cool outside will be a project for later.

2. The screen capture image inadvertently omits a

copyright notice “Imagery ©2024 Airbus, Maxar Technologies” that was

present in the original DishPointer image, but not in the full-screen

version.

3. The Raspberry Pi at the antenna location had a

reliable WiFi connection to the LAN router (opposite end of house),

without the aid of a WiFi extender. This good fortune was also

unexpected!

Project descriptions on this page are intended for entertainment only.

The author makes no claim as to the accuracy or completeness of the

information presented. In no event will the author be liable for any

damages, lost effort, inability to carry out a similar project, or to

reproduce a claimed result, or anything else relating to a decision to

use the information on this page.

Getting started: The .jpg image above does not do justice

to the original high-resolution .png from GOES-16. Click the

link and zoom-in to view amazing detail.1

Before describing how this

image and many others were successfully received and decoded I will

briefly recount the highlights or lowlights of my first attempt to

receive GOES-16 in October 2018. A previous owner of our house had

abandoned a

DirecTV dish in the backyard. I kept the steel post and

azimuth/elevation mount,

but replaced the TV dish with one that was said to be good for

receiving the NOAA GOES satellite. The antenna that I purchased was

manufactured by ZDA Communications, and labeled 1850–1900 MHz, about

200

MHz above the frequency of interest. This first attempt at GOES

reception was doomed, not on account of the antenna, but rather of my

failure to understand or fully appreciate the nature of the challenge.

Getting started: The .jpg image above does not do justice

to the original high-resolution .png from GOES-16. Click the

link and zoom-in to view amazing detail.1

Before describing how this

image and many others were successfully received and decoded I will

briefly recount the highlights or lowlights of my first attempt to

receive GOES-16 in October 2018. A previous owner of our house had

abandoned a

DirecTV dish in the backyard. I kept the steel post and

azimuth/elevation mount,

but replaced the TV dish with one that was said to be good for

receiving the NOAA GOES satellite. The antenna that I purchased was

manufactured by ZDA Communications, and labeled 1850–1900 MHz, about

200

MHz above the frequency of interest. This first attempt at GOES

reception was doomed, not on account of the antenna, but rather of my

failure to understand or fully appreciate the nature of the challenge.

To adjust antenna

elevation angle, I used essentially the same procedure in 2018 as in

the

effort to be described on this page. Back then the tool set consisted

of a plastic protractor and small ‘pocket’ level; while for try #2, a

digital protractor and larger level were used. It was impossible to

photograph measurement while using the larger implements—not enough

hands. However, in each case the protractor was placed alongside the

‘boom’,

such that the

angle of the boom with respect to the horizon (bubble level)

could be

measured after each adjustment. The mounting mechanism, inherited from

the old DirecTV setup, displayed the same angle measure, and agreed

within a degree or so with protractor readings.

To adjust antenna

elevation angle, I used essentially the same procedure in 2018 as in

the

effort to be described on this page. Back then the tool set consisted

of a plastic protractor and small ‘pocket’ level; while for try #2, a

digital protractor and larger level were used. It was impossible to

photograph measurement while using the larger implements—not enough

hands. However, in each case the protractor was placed alongside the

‘boom’,

such that the

angle of the boom with respect to the horizon (bubble level)

could be

measured after each adjustment. The mounting mechanism, inherited from

the old DirecTV setup, displayed the same angle measure, and agreed

within a degree or so with protractor readings.

Drinking straws are about the same diameter as power cords, and should

fit through the dry box’s water-resistant openings. I purloined a pair

of curved steel straws from the pantry and cut one of them with the

Dremel tool to test the idea. The curved piece fit snugly. According

to my admittedly poor intuition about such things, two

cut pieces placed at opposite ends of the box, and turned downward on

the outside, should allow moving air to pass out- or in- when the lid

is shut. This whole cooling business may be a pseudo-concern, as rain

falling on the lid must surely cool the inside air; and, as noted, if

rain is not expected, the box can be left open.

In any case, it is also reassuring that the Raspberry Pi has built-in

sensing of core

voltage and temperature. —I made a convenience script to format and

display these

parameters (image left).

Drinking straws are about the same diameter as power cords, and should

fit through the dry box’s water-resistant openings. I purloined a pair

of curved steel straws from the pantry and cut one of them with the

Dremel tool to test the idea. The curved piece fit snugly. According

to my admittedly poor intuition about such things, two

cut pieces placed at opposite ends of the box, and turned downward on

the outside, should allow moving air to pass out- or in- when the lid

is shut. This whole cooling business may be a pseudo-concern, as rain

falling on the lid must surely cool the inside air; and, as noted, if

rain is not expected, the box can be left open.

In any case, it is also reassuring that the Raspberry Pi has built-in

sensing of core

voltage and temperature. —I made a convenience script to format and

display these

parameters (image left).